Sometimes it feels like everything in Mongolia is harder than it has

to be. Information is a precious commodity, there are few firm answers,

and chaos—not order—is the order of the day.

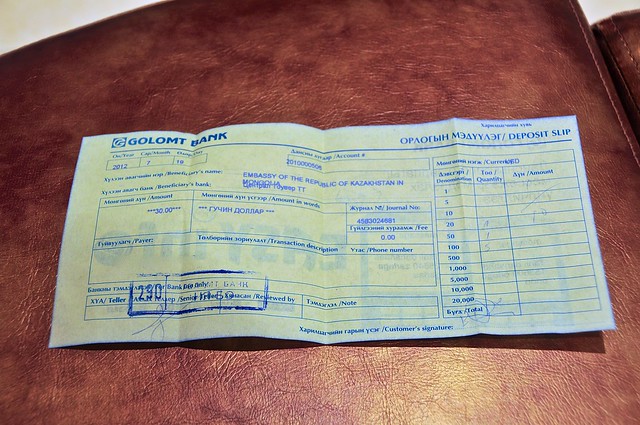

This extended to the process of getting a Kazakh visa. I had initially dropped by the Kazakh embassy during my first stint in UB, only to be told that they were closed during Naadam and to come back after. Fair enough, except they only told me this after sending me away for a few hours and telling me to come back later that day. After returning from Kharkhorum I went there and they wouldn't take my application since the consul was out of the office for the day. This seemed a bit strange: why would they need the consul, and why would I have to talk to him? They asked me to return in a day or so. I returned the next day later, and the consul was still away, they accepted my application after asking me some questions about why I wanted to visit. I had to go pay the application fee at a not-so-close bank, and then return with the receipt ($30 for a single-entry visa valid for a fixed 30-day period—and not 30 days after entering), and then wait 7 days for it to be ready. It took me four visits to the embassy in order to apply for my visa.

Go to a supermarket, and your choices aren't much greater. The biggest aisles are for dairy, hard candy, and vodka—and not necessarily in that order.

Vodka is pitifully cheap, to the extent you can get a bottle for well under a dollar. There are dozen of brands whose names are all variations on Chinggis Khan, but the blame lies squarely on the Russians. Up to a quarter of Mongolian men are alcoholics, and the introduction of vodka was a shock to a people who were socially and biologically accustomed to drinking nothing stronger than airag and its alcohol content of about 3%. You'll often encounter drunk Mongolian men, and sometimes they like to fight. Usually not with foreigners, but they probably wouldn't say no, either.

Less of a priority are things like fruit and vegetables. Part of this is because of the remoteness of UB and the lack of transportation to the capital, which means that imported fresh foods are quite expensive and likely the worse for wear by the time they make it to the shelf.

I decided there are two decent choices when it comes to eating in UB: places that seem really popular, and places that serve Russian food. Russian food at least has the pretense of seasoning and spices, while popular food is self explanatory. Perhaps the best popular place I found is the soup and noodle place below.

I find this way of thinking objectionable on so many levels.

From an economic perspective, I don't think there's anything terribly wrong with expecting people who earn more to pay more. I mean, it's the idea behind the graduated income tax rates that pretty much every Western country uses. It's also true that this kind of discrimination can go both ways: in India a certain number of train tickets are reserved for foreigners, so that they don't have to book in advance or have difficulty catching the train; while in Thailand tourists can actually catch foreigner-only buses that are cheaper than the buses that are available to regular Thai people (they are only taxed and insured as public transportation if they carry Thai citizens). Foreigners never complain about this. And foreigners certainly show little concern for the unfairness that results when huge influxes of foreign money ends up pricing locals out of the market for things like real estate and accommodation (which happens in places with large ex-pat communities, like Phnom Penh).

But what's really objectionable is the sort of hipster-tourism kind of thinking it exemplifies. It's a way for people who have more time than money to glorify their situation at the expense of those who have little time but more money, and the justification for this is the guise of "authenticity." But the authenticity of travelers is largely in their own mind. Sure, they may take local transportation and live cheaply. But they also pretend that smoking hash in India or taking opiates in the golden triangle is culturally authentic—when in fact they're doing little other than indulging their own self-serving stereotypes, supporting the drug trade, and helping to destroy the moral and cultural fabric of traditional communities. There's not a lot that's culturally authentic about comparatively wealthy western tourists who traipse around conservative communities (and even religious sites) in shorts and tank tops, drink heavily, and show off their tattoos and piercings while generally ignoring local customs as they head for the nearest vendor of banana pancakes. "Tourists" may have somewhat less local knowledge and their ability to stay in expensive accommodation and take guided tours may insulate themselves from the locals, but you rarely see them behaving as self-indulgently and destructively as the self-proclaimed "travelers."

Of course, since Mongolia is a bit off the beaten path even for long-term travelers, it's a good credential for these kinds of status-whores to collect.

There was a group of French youth staying at Idre's who had just returned from this sort of trip, one of whom you could smell from the kitchen when he was in the lunge. I have no idea how his friends put up with him and actually sat beside him, but in the two days we were both there he didn't take a shower. I'm not sure I understand this, but I think that for some Europeans the allure of unspoilt wilderness is very romantic and deeply appealing (lot of Germans go to the Canadian Yukon for just this reason, though I doubt that many completely abandon civilization).

Mongolia's tourist mix is different than you see in most places, as it seems to get relatively equal numbers of long-term travelers and European travelers on relatively short vacations. There are very few North Americans, and many people only see UB as part of a greater Trans-Siberian train trip.

This extended to the process of getting a Kazakh visa. I had initially dropped by the Kazakh embassy during my first stint in UB, only to be told that they were closed during Naadam and to come back after. Fair enough, except they only told me this after sending me away for a few hours and telling me to come back later that day. After returning from Kharkhorum I went there and they wouldn't take my application since the consul was out of the office for the day. This seemed a bit strange: why would they need the consul, and why would I have to talk to him? They asked me to return in a day or so. I returned the next day later, and the consul was still away, they accepted my application after asking me some questions about why I wanted to visit. I had to go pay the application fee at a not-so-close bank, and then return with the receipt ($30 for a single-entry visa valid for a fixed 30-day period—and not 30 days after entering), and then wait 7 days for it to be ready. It took me four visits to the embassy in order to apply for my visa.

|

| Visa receipt. |

Shopping and eating in UB

The food in UB is pretty bad. Despite being in the city, the diet is still meat and dairy heavy, supplemented by root vegetables. There aren't that many international options, although you can get Korean salads at some markets. Go up and down Peace Avenue at the options still seem limited.Go to a supermarket, and your choices aren't much greater. The biggest aisles are for dairy, hard candy, and vodka—and not necessarily in that order.

Vodka is pitifully cheap, to the extent you can get a bottle for well under a dollar. There are dozen of brands whose names are all variations on Chinggis Khan, but the blame lies squarely on the Russians. Up to a quarter of Mongolian men are alcoholics, and the introduction of vodka was a shock to a people who were socially and biologically accustomed to drinking nothing stronger than airag and its alcohol content of about 3%. You'll often encounter drunk Mongolian men, and sometimes they like to fight. Usually not with foreigners, but they probably wouldn't say no, either.

Less of a priority are things like fruit and vegetables. Part of this is because of the remoteness of UB and the lack of transportation to the capital, which means that imported fresh foods are quite expensive and likely the worse for wear by the time they make it to the shelf.

|

| Supermarket vegetables. I've seen better looking carrots. |

I decided there are two decent choices when it comes to eating in UB: places that seem really popular, and places that serve Russian food. Russian food at least has the pretense of seasoning and spices, while popular food is self explanatory. Perhaps the best popular place I found is the soup and noodle place below.

|

| One of the better and more popular restaurants. |

|

| They also serve a lot or ramen-style soups and salads. |

Two of the special kind of people who visit Mongolia

Mongolia is a difficult country to travel in. I see this as a negative, but others see this as a positive. Where I see it as an obstacle to actually seeing things, others see it as a status symbol. I go to Mongolia and feel bad because I didn't see as much as I could have, or should have; they go to Mongolia and congratulate themselves on being authentic, hardcore travelers who do things that mere tourists don't.1. Travelers collecting badges

These are the kind of people who insist on being called travelers and take offense at being called tourists. As one very drunk Austrian-Australian explained to some French girls at the hostel, tourists are people who go to countries for a little while and don't make any effort to learn about those countries. More about that in a second, but his real objection seemed to be that they didn't take the time to learn how much things cost for the locals, so the end up wildly overpaying for things, which led to the expectation that poor travelers like him would also pay high prices for things. He held out India as a particularly pernicious example of this, saying that the formalization of this through official foreigner and local prices at many sights was a horribly unjust effect of free-spending tourists.I find this way of thinking objectionable on so many levels.

From an economic perspective, I don't think there's anything terribly wrong with expecting people who earn more to pay more. I mean, it's the idea behind the graduated income tax rates that pretty much every Western country uses. It's also true that this kind of discrimination can go both ways: in India a certain number of train tickets are reserved for foreigners, so that they don't have to book in advance or have difficulty catching the train; while in Thailand tourists can actually catch foreigner-only buses that are cheaper than the buses that are available to regular Thai people (they are only taxed and insured as public transportation if they carry Thai citizens). Foreigners never complain about this. And foreigners certainly show little concern for the unfairness that results when huge influxes of foreign money ends up pricing locals out of the market for things like real estate and accommodation (which happens in places with large ex-pat communities, like Phnom Penh).

But what's really objectionable is the sort of hipster-tourism kind of thinking it exemplifies. It's a way for people who have more time than money to glorify their situation at the expense of those who have little time but more money, and the justification for this is the guise of "authenticity." But the authenticity of travelers is largely in their own mind. Sure, they may take local transportation and live cheaply. But they also pretend that smoking hash in India or taking opiates in the golden triangle is culturally authentic—when in fact they're doing little other than indulging their own self-serving stereotypes, supporting the drug trade, and helping to destroy the moral and cultural fabric of traditional communities. There's not a lot that's culturally authentic about comparatively wealthy western tourists who traipse around conservative communities (and even religious sites) in shorts and tank tops, drink heavily, and show off their tattoos and piercings while generally ignoring local customs as they head for the nearest vendor of banana pancakes. "Tourists" may have somewhat less local knowledge and their ability to stay in expensive accommodation and take guided tours may insulate themselves from the locals, but you rarely see them behaving as self-indulgently and destructively as the self-proclaimed "travelers."

Of course, since Mongolia is a bit off the beaten path even for long-term travelers, it's a good credential for these kinds of status-whores to collect.

2. Wannabe cavemen

The other type is of those who seem to want to lose themselves in nature. I don't know if it's the romance of communing with nature or the desire to prove just how much they can take, but there seem to be people for whom the difficulty and deprivation of travel in Mongolia is the goal. These kinds of tourists are likely to go hiking around the lake of Khuvsgul Nuur—itself an 20+ hour bus ride from UB—or go even farther to western Mongolia. There they will engage in some sort of trekking that may involve horses and fishing, and definitely involves some camping, but absolutely does not include showering.There was a group of French youth staying at Idre's who had just returned from this sort of trip, one of whom you could smell from the kitchen when he was in the lunge. I have no idea how his friends put up with him and actually sat beside him, but in the two days we were both there he didn't take a shower. I'm not sure I understand this, but I think that for some Europeans the allure of unspoilt wilderness is very romantic and deeply appealing (lot of Germans go to the Canadian Yukon for just this reason, though I doubt that many completely abandon civilization).

Mongolia's tourist mix is different than you see in most places, as it seems to get relatively equal numbers of long-term travelers and European travelers on relatively short vacations. There are very few North Americans, and many people only see UB as part of a greater Trans-Siberian train trip.

No comments:

Post a Comment