Lanzhou: welcome to the west

I had no idea where I would go from Lanzhou: on the one hand, I thought I might want to take a trip up the Yellow River to the Buddhas and caves of Bingling Si, and/or make the sidetrip up to the town of Xiahe and the Tibetan Labrang monastery there. I thought I would figure it out in Lanzhou.

I arrived at the train station in the morning, and headed to the the Lanzhou Huar (Flower) Hostel. They weren't in any guidebooks, but I had picked up a pamphlet in Shanghai (I think), and found instructions to them. It took about an hour to get there by bus because the directions weren't the greatest, and when I arrived I was curtly told they don't accept foreigners. This was really strange, especially since they had the English-language pamphlets on their reception desk! They said it was because of government regulations, and they weren't very helpful about telling me if there were any other cheap places in Lanzhou. I asked if I could use their bathroom, and they said it would cost 10 yuan to do so! Not very impressive (especially since it seems they had lacked the necessary permit to accept foreigners since at least 2011, yet were advertising themselves to foreigners during this time); I really don't understand the inability of people in hospitality industries to be helpful when they have to turn people away.

I backtracked to the station, and looked for the cheap hotels listed in LP. No luck, as they were either closed or not accepting foreigners. I figured that since I wouldn't be able to stay in Lanzhou that Binling Si was out, and that I would head to Xiahe. Unfortunately, the bus station listed in LP had been torn down. Well, at least the LP was still right about where the train station was.

I then tried to go to an internet cafe and see if I could figure out where to catch the bus to Xiahe and how to get there. Except the government requires you to swipe your RFID-chipped ID card in order to get online, effectively shutting out foreigners from using the internet. Thankfully, the owner over-ruled the attendant and swiped me in with her own ID card, letting me go online.

I managed to find the location of the new Bus Station as well as the South Bus Station, and determined that there should be buses running to Xiahe into the afternoon. I went the the new Bus Station (a couple of blocks east on the road in front of the station), only to find that the buses to Xiahe only run from the South Bus Station. I hopped a city bus to the vicinity of the South Bus Station, then got off and wandered around until I eventually found it, and got a ticket to Xiahe in the early afternoon—about 7 hours after arriving in Lanzhou.

|

| Crossing the train tracks on my way to Lanzhou's South Bus Station (which is actually well west of the main train station, and near the Lamnzhou West Train Station). |

Although Lanzhou is already at an elevation of 1500 meters, the road steadily climbs to Xiahe, which is at 2900 meters. The road starts out running through dusty, dry mountains, completely devoid of vegetation except for small fields and trees planted by farmers. Then the road begins to climb in earnest, and the scenery turns decidedly green as it does. Lush fields and trees become the rule in the valleys between the increasingly-high mountains, but the biggest surprise being the abundance of new and impressive mosques that seem to pop up every few kilometers.

As we push higher and higher, the valleys narrow but the scenery remains quite green if not as lush. We stop seeing mosques, and before we know it we're pulling into Xiahe. The bus station is in the Chinese section of town, and the Tibetan quarter doesn't begin until a little further up the valley, so the introduction to the town is familiar. The closer you get to Labrang, the more Tibetan the town becomes.

As I arrived late—at around 5:00—all of the hostels were full. The Redrock Hostel said I could sleep on the floor (albeit at full price), so I ended up doing that. I thought their bathrooms—although appearing clean—were a little smelly, but it would turn out that by regional standards they were actually quite good.

Xiahe

Xiahe is home to the renowned

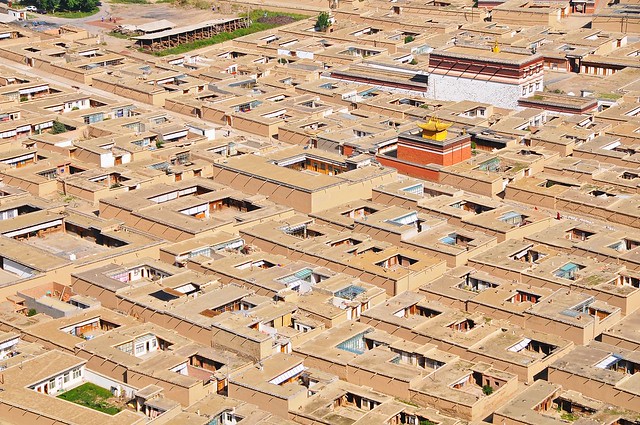

Labrang monastery, which is said to be the third-largest Tibetan Buddhist monastery in the world. It once housed 4,000 monks, and although that number has dropped to an official 1,500, some claim that there are actually about 2,000 monks studying there. Regardless, it's big and there are lots of monks, and even more pilgrims.

A

kora is a circuit that the devout walk around religious site, and you typically do it in a clockwise direction. Labrang has two

koras: an inner

kora that simply surround the monastery itself, and is lines with prayer wheels; and an outer

kora that runs along the mountain behind the monastery.

After leaving my stuff at the Redrock Hostel, I went out to explore Labrang for a couple of hours before it got dark.

|

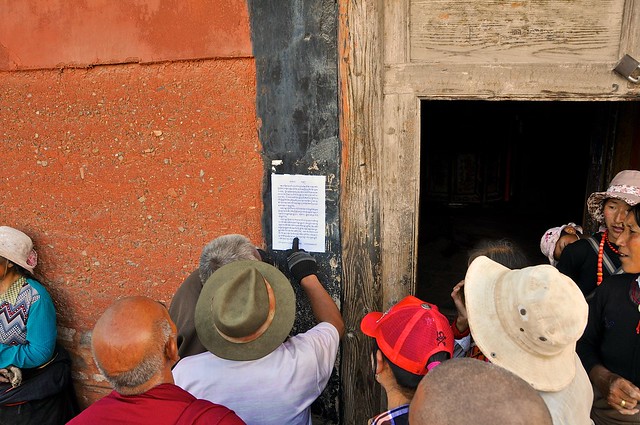

| Tibetans reading notices on a dusty street at the edge of Labrang. While the Chinese section of town is all paved streets and newer buildings, the Tibetan sections are (or were) in a much greater state of disrepair. |

|

| Along the main street from town to the assembly hall. |

|

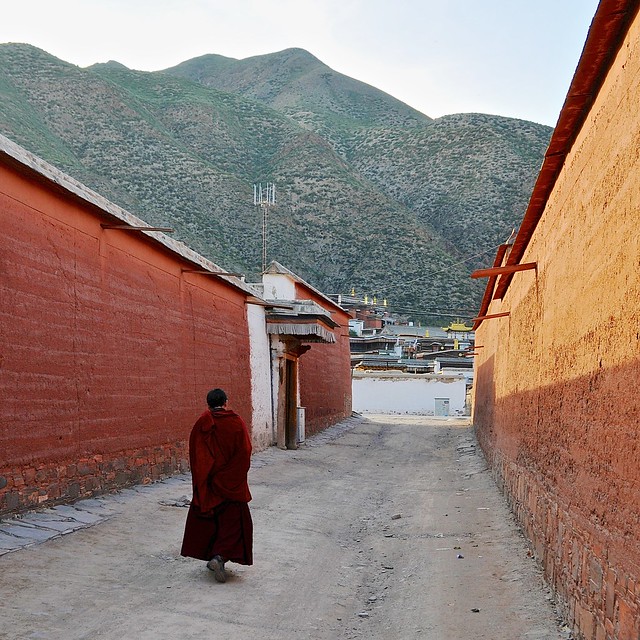

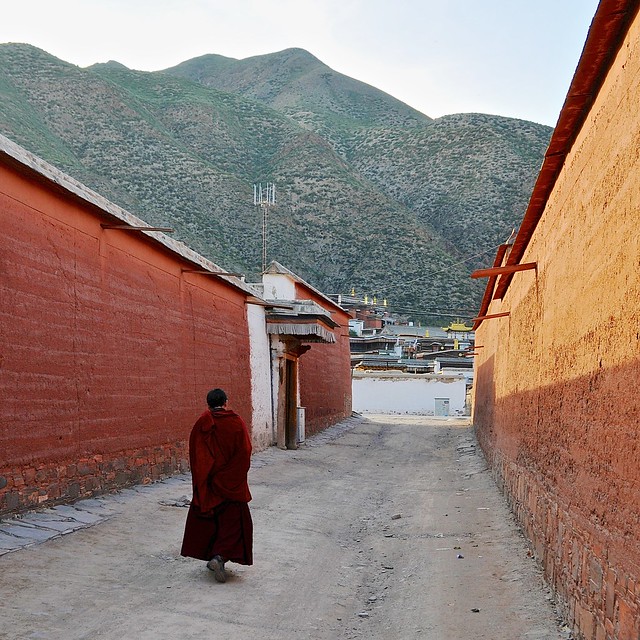

| Dirt side-street leading to monks' quarters. |

|

| The outer kora runs along the mountain ridge above. |

|

| Lots of work was being done in the monastery. They seemed to be installing street kerbs here. |

|

| And new electrical boxes/transformers also lined the street. |

|

| Old-style monk dormitories dot the mountain. |

|

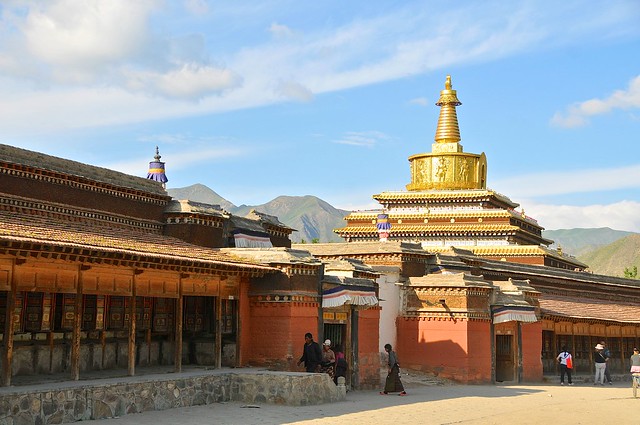

| The main assembly hall and plaza. |

|

| The main entrance to the assembly hall. |

|

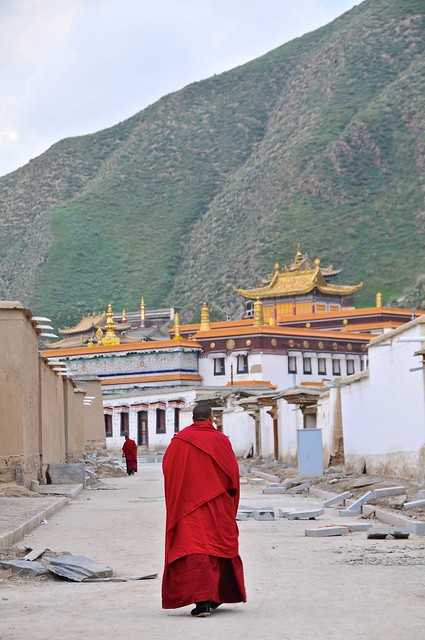

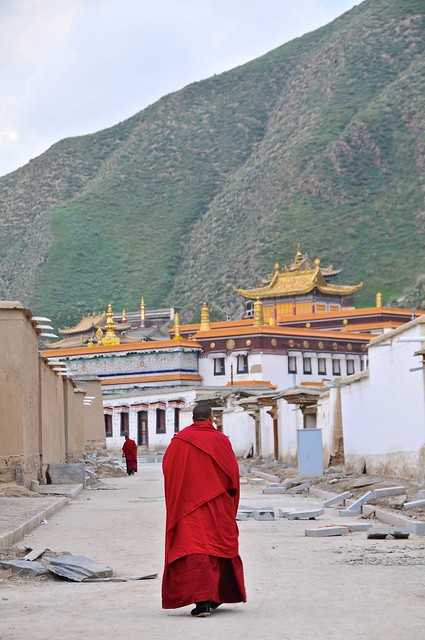

| Monks walking into town. |

|

| Looking back as I return to town. |

|

| Looking towards the southern mountains. |

|

| I was walking on a side street when these two monks ran past, one carrying the other over his shoulder, the both of them laughing uproariously. Here we see the dismount. |

|

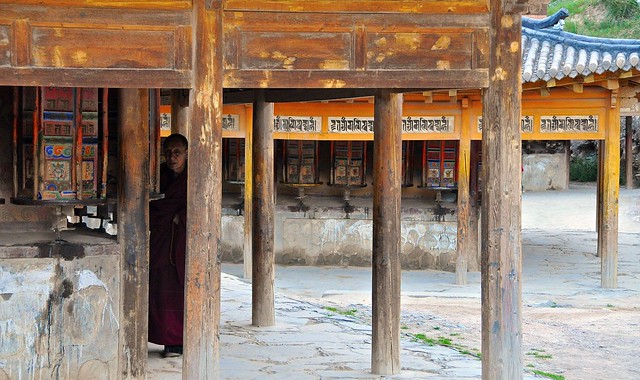

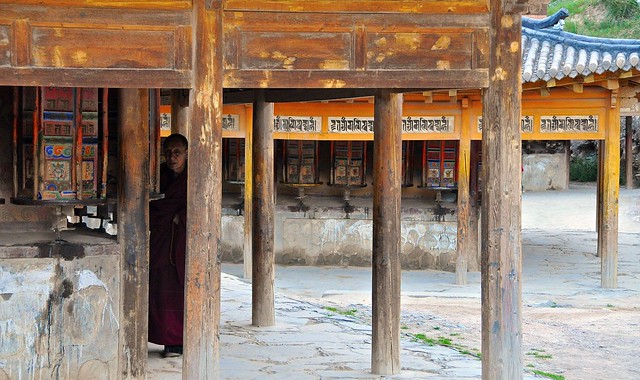

| A monk turns prayer wheels. |

|

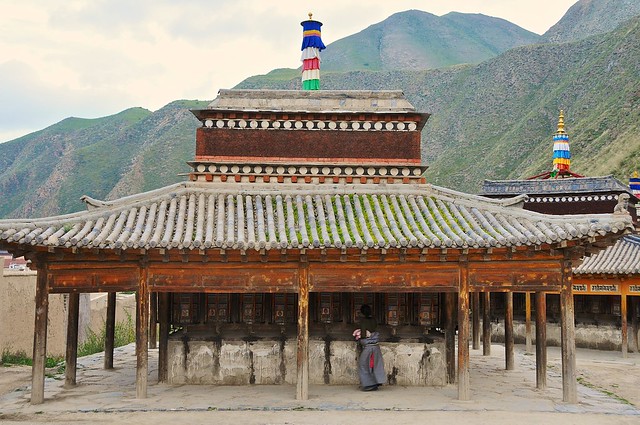

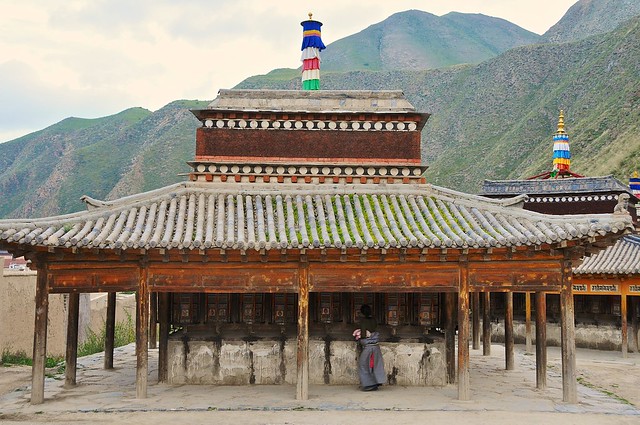

| Small building of prayer wheels requires you to do a mini-kora while on the inner kora. |

|

| Monk rounding the corner. |

|

| Pilgrim turns a wheel. |

|

| Monks on the ridge overlooking the monastery. |

|

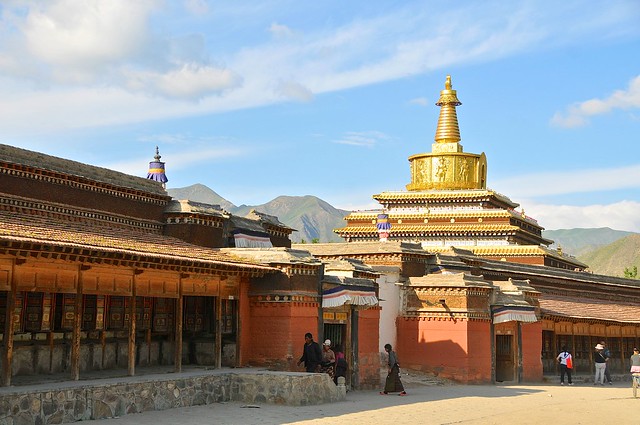

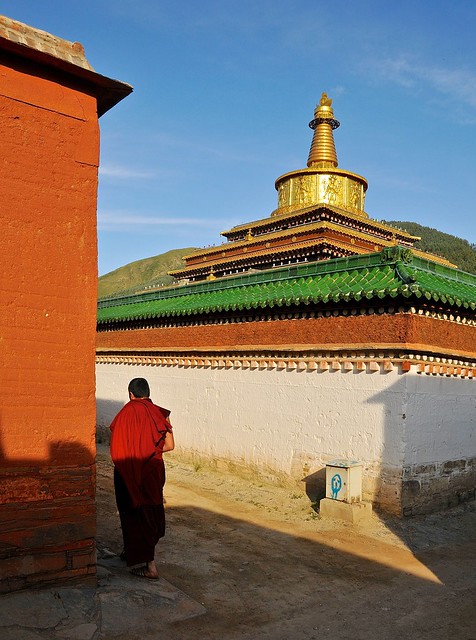

| Circumambulating around a stupa. |

|

| Around they go. |

|

| Local Tibetan kids and pilgrims. Like Mongolians, Tibetans are pretty good at wearing hats. |

Day 2

The next day I searched for a new place to stay, and settled on the Tibetan Overseas hotel, which offers dorms on the ground level. The rooms were quite pleasant, as they had sunny windows facing the spacious interior courtyard/parking lot, and some of the younger staff spoke very good English and were quite friendly.

In my dorm room was an Israeli girl who had recently finished her military service and was in the middle of the typical post-service trip. This frequently results in brash Israelis behaving badly, and I suspect she had already had her share of that in India along the drug-fueled Hummus Trail. Helit was friendly and outgoing, though, and when she saw me making some 3-in-1 instant coffee (little powder packets that contain instant coffee, sugar, and milk, and which are popular throughout Asia), she offered to make me some of the coffee she had, with real milk. She told me that the coffee she was going to use was famous in Israel and that it was so good she carried around a jar of it with her: "In Israel, we call it Taster's Choice." Hmmm, OK. Well, it was better than my Nescafe 3-in-1.

There was also a Korean-German girl who had come to China after a short stay in Kazakhstan, whose women she praised as being remarkably beautiful. Mindful of my conversation in Hiroshima with the Turkish-German, I asked her about her experience. She didn't think that being Korean affected her much at all, which was a bit surprising in some ways, but totally not in others (obviously Asian -Americans have very different experiences than African-Americans, for example). And since the subject of the toilets at the hostel inevitably came up, I teased her about

German shelf toilets—which are designed to leave your poop sitting on a porcelain shelf, exposed to the air, until you flush—and how maybe she could relate to the Chinese toilets. She said she had never noticed this feature of German toilets, but admitted that they sometimes make fun of old people in Germany by pretending to talk about their poop—apparently this is something older Germans like to discuss.

Anyway, after coffee, we went to see more of Labrang.

|

| Monks' boots outside the assembly hall. This was only a side entrance: dozens of identical boots lie outside the main entrance. |

|

| Stupa next to the assembly hall. Since it's not part of the kora, no one really walks around this one. |

|

| Monks along the inner wall of the assembly hall. |

|

| Monks and tourists just inside the assembly hall courtyard entrance. The Chinese are decked out in shorts, including short-shorts. This sort of disrespectful dress isn't unilquely Chinese by any stretch of the imagination (you'll see Westerners dressed even worse at just about every temple in Southeast Asia), but it does suggest just how effectively the Chinese have been cut off from their own religious traditions, including Buddhism. |

|

| The roof detail seems very Chinese, which may be because almost all of the Labrang buildings were rebuilt or restored in the 1980s or later, after the end of the Cultural Revolution. |

|

| Monks leave the assembly hall and collect their boots. |

|

| Only a few Chinese tourists. |

|

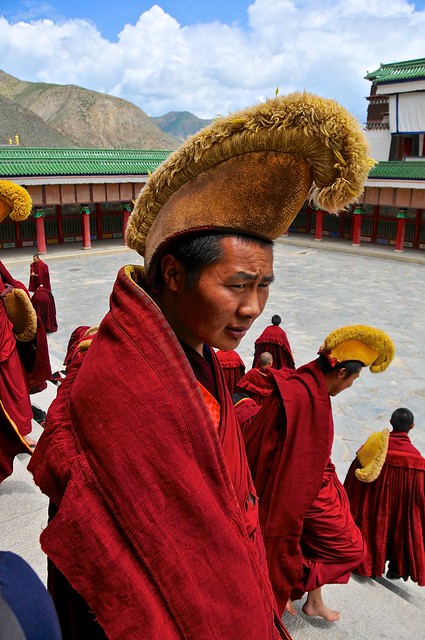

| Interesting, non-Han faces... but not stereotypically Tibetan, either. |

|

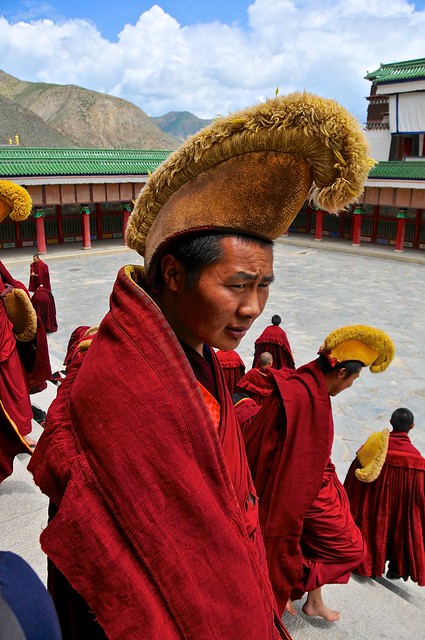

| As you may have guessed, they are from the yellow-hat sect. |

|

| School's out, and so are we. |

After seeing Labrang, Helit and I headed up the valley towards the Sangke grasslands, which are 12 km away. We started walking on the northern side of the valley, through farmland, before switching over to the south side when we came across a small electrical dam that allowed us to cross to the southern side. I was game for walking, but Helit decided to try her luck hitchhiking, and we were soon picked up. She had hitchhiked in Qinghai, and said that Chinese don't expect payment, but I figured we should offer anyway. They refused the money.

Helit told me about how she and another girl wandered around parts of Qinghai, walking by day and then at night going up to random doors and knocking on them, and begging bewildered Tibetans if they could stay the night. This isn't something I can imagine doing (and can you imagine if tourists tried that in your country?), even though they obviously found a place to stay every night. Heck, as fair-haired white girls who could be easily identified as foreigners, I would have imagined that they would have gotten quite a few invites had they just pitched a tent somewhere.

Anyway, the Sangke grasslands were a bit of a disappointment (and as proof of this I have exactly zero photographs). I mean, it really just was some grassy fields in a wide valley, with lots of tourist restaurants and the like at the edge. After wandering around for a bit and getting a bit of food (strangely, the menu in a restaurant indicated that it would be something like 15 yuan for rice, even though this is usually like a couple of yuan, so we were worried... but they ended up charging normal prices), we hitched back to Xiahe.

|

| A rare nun on the kora. She wears a glove on her right hand to protect it from the wear of turning so many prayer wheels. |

|

| Gloved Tibetan pilgrim. |

|

| A couple of kids play in front of the stupa. |

|

| Most people doing the kora were quite old, including this monk. |

|

| Spinning the long line of prayer wheels. The traditional hairstyle for Tibetan women is two braids that are tied together into a circle at the end. |

|

| The younger man and his son in blue jeans are relatively rare sights. |

That night we met a Japanese guy and a Swiss guy staying at the hostel, and we all went out for dinner at a popular Tibetan place, Nomad Restaurant. I can't say that the Tibetan food I tried impressed me that much, although it certainly attempted more flavours than Mongolian cuisine does.

There were anti-Japanese riots occurring in China at around that time (the Chinese tolerate them as a way for the population to blow of steam and vent in a direction other than the government, as well as to foster a sense of nationalistic unity), so I asked him if he had any problems as a Japanese tourist. He said that for the most part he didn't, and that the more educated people didn't really care, but that he was actually being given a hard time by the Chinese in his room at the hostel: when they asked him where he was from, and he told them he was Japanese, they started to act rudely.

Later that night, at the hostel, I saw him in the hallway outside his door and stopped to talk to him. The Chinese in his room had the TV on really loud and would turn it up if he turned it down and wanted to sleep, and as I was talking to him one of the Chinese guys left the room, and instead of taking one step to walk around us, gestured to Hiki that he should move out of his way. Then, when he returned to his room a couple of minutes later, they locked the door and didn't want to get up and unlock the door to let him in. Although I think it's typically Chinese to not care about how loud the TV is or anyone else wanting to sleep, the other things seemed unusually rude even for Han, so we told him he could switch rooms and stay with us instead of with the Chinese guys.

Day 3: the hills are alive with the sound of flashbangs

Those rude Chinese guys were actually the drivers for a tour company, which may explain their lack or education or sophistication (which you wouldn't entirely expect from a fellow traveler). The next morning they made their mark in the toilets (which were, by far, the worst thing about the hostel): I went in and found that there was a huge pile of shit almost overflowing in the squat toilet, with flies buzzing all around, as someone hadn't even made an attempt to flush it. (A Chinese guy I met in Iran later described this as a Nihao toilet, as someone has left his greeting to you.)

After using the other toilet, which has a bit less shit in it, I decided to explore the hills around the monastery. I had seen the monks sitting on the ridge above the monastery, and I figured there must be paths up there. So I started by heading up the road between Labrang and the town, passing a small collection of houses and terraced fields, the turning up a road that eventually led to a grassy ridge bearing much evidence of picnics.

|

| A blackbird on the grassy ridge. |

|

| Up the valley towards to Sangke grasslands. |

|

| Shepherdless sheep appear up here. |

|

| Sheep on the hillside. |

|

|

| Unpalatable or fast-growing grass sprouts skyward. |

|

| Panorama looking back towards Xiahe. |

|

| Looking south over the mountains. |

|

| East over this valley, towards prayer flags. |

|

| These bundles of wooden poles adorned with khatag scarves and prayer flags are called latse. Latse are intended to look like bundles of arrows, and usually erected on high places, or places where local gods reside. New sticks are added every anniversary. There seem to be clear similarities with Mongolian ovoo. White lungta paper squares printed with wind horses are scattered by visiting pilgrims. That's Xiahe down on the left. |

|

| Looking northeast. Apparently these peaks level out into a grassy plateau after a few more kilometers. |

|

| A road leads to a ruined building. |

|

| Looking back, before I press on. |

|

| Last picture of this latse, I promise. |

|

| Some of these locations are pretty inaccessible, and I wonder how many people visit them, but you also see evidence of new latse being built all the time. |

|

|

While I was up the mountain I heard a series of large bangs, as though someone was letting off huge firecrackers down in the Chinese end of the village. Or at least that is what I secretly hoped; I internally wondered whether the town would be a war zone or under curfew when I got back. This wouldn't be unprecedented, given that the town had been largely closed off to foreign visitors before 2008.

|

| I started up by coming up the road from Xiahe on the left, passing by the houses, then taking the road up the ridge in the middle of the picture. Then I skirted the entire valley by following the ridge around to where the picture was taken. |

|

| This hawk kept his eye on me. |

|

| Labrang, with the outer kora's ridge in the foreground. |

|

| Looking up the valley from close to Xiahe. |

|

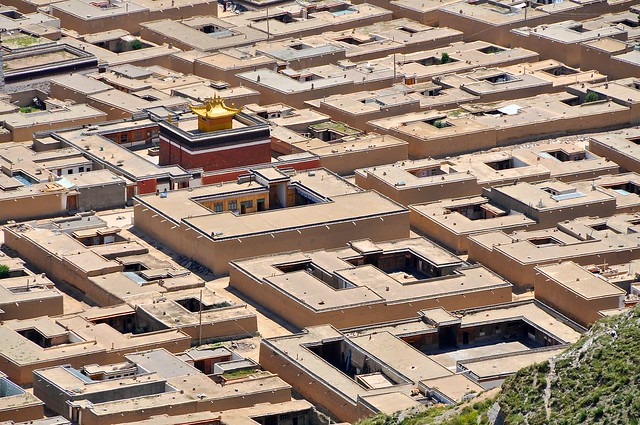

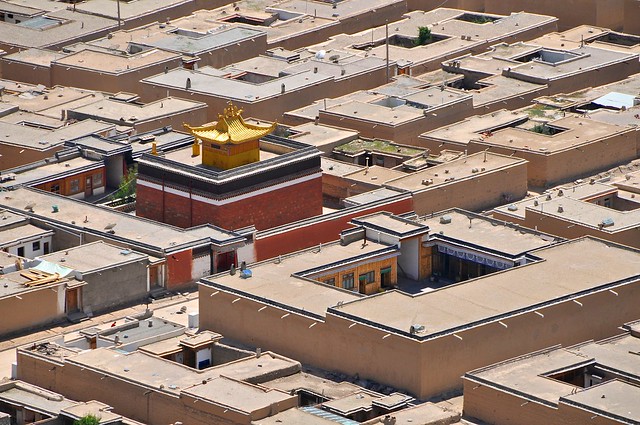

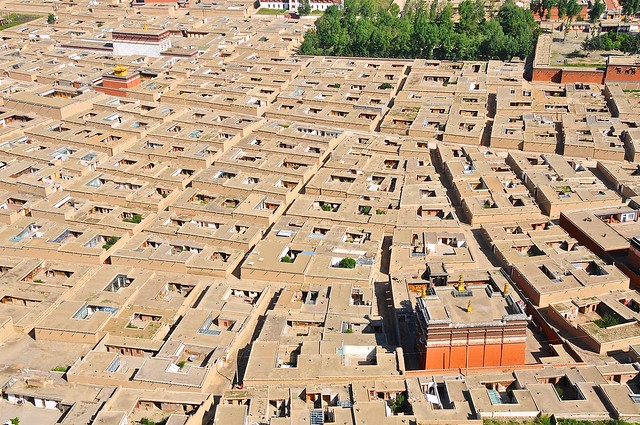

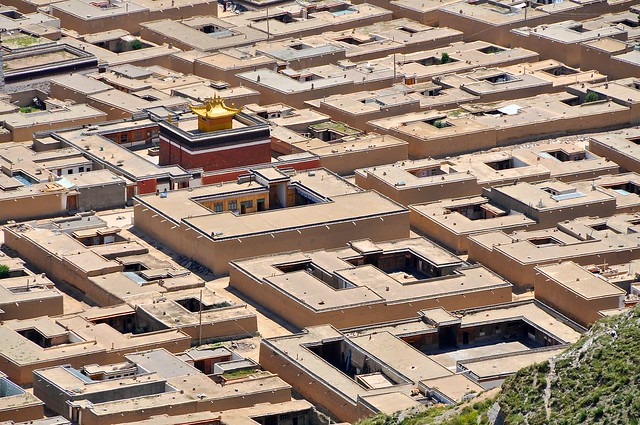

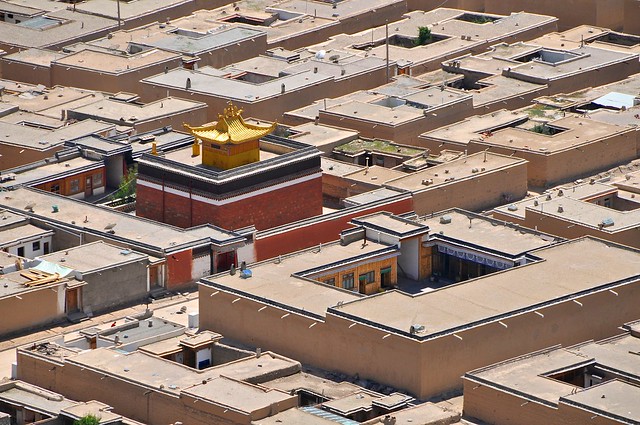

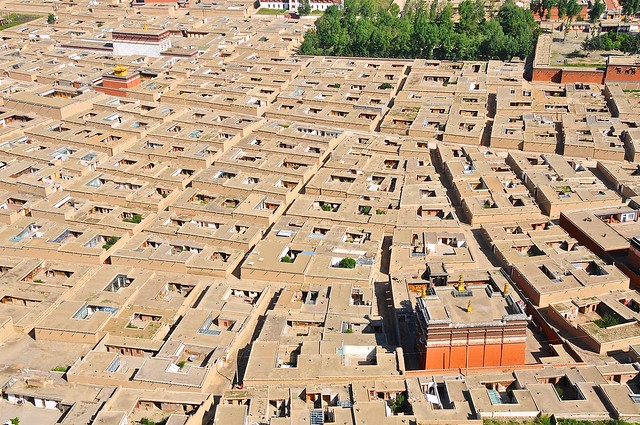

| Monks' quarters at Labrang. |

|

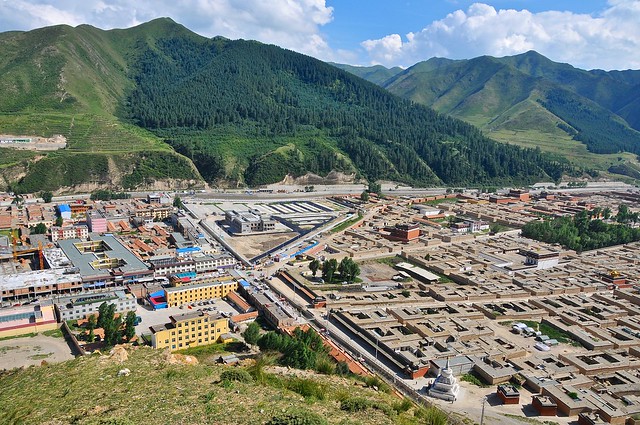

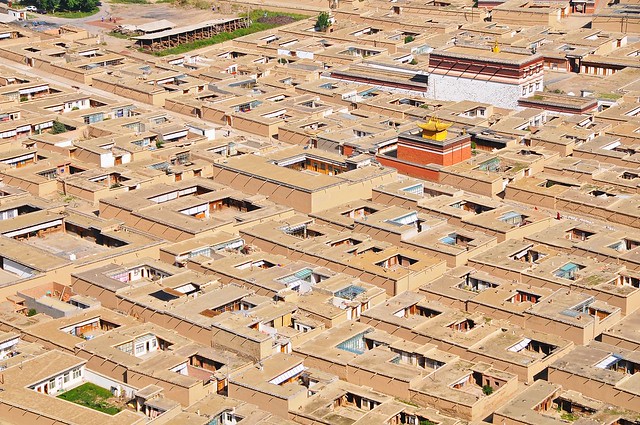

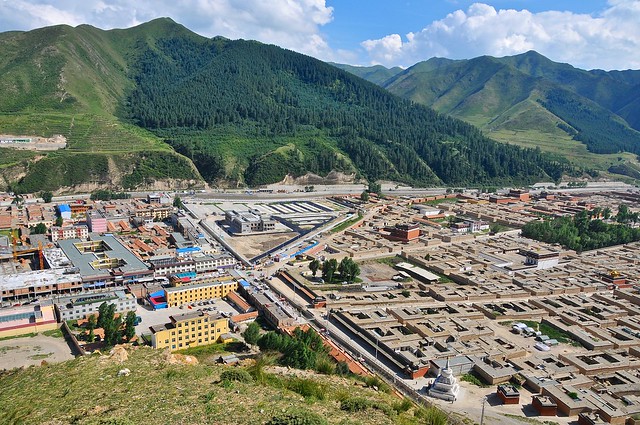

| A panorama of Xiahe: the Chinese quarter is on the left, Labrang is on the right (with more of the Tibetan quarter around the mountain to the right), and Hui in the middle. |

|

| The assembly hall and main monastery buildings are visible. |

|

| Add caption |

|

| I arrived back at Labrang to see these rows of police in riot gear. This was taken from in front of the Overseas Tibetan Hotel. |

|

| The police retreat to their barracks, which are about 100 meters from Labrang. |

|

| The police are garrisoned in that building center-left, just outside the monastery. |

I wasn't able to get a clear picture of what happened until a day or so later, but it appears that while I was up in the hills the monks received a report that someone in a village about 100 km away had self-immolated (it appears that this occurred in Hezuo, some 65 kilometers away, and that the immolator was a young woman named

Dolkar Tso). They decided they would march there to show their respects. As the monks were leaving Xiahe, the police stopped them and deployed smoke grenades in order to force them to turn back. They also prevented the monks in Labrang from communally praying for the deceased, and they closed the monastery to all visitors, telling tourists a few different stories, with the most common being that the monastery was closed because of visiting dignitaries. The internet in Xiahe was also cut for the next 24 hours, and the entire town was declared off limits for October and November of 2012.

Of course, at the time I had no idea what was really going on, and I didn't want to be too inquisitive with all of the police swarming around lest I get anyone in trouble.

|

| A yak tied up to construction scaffolding, on which carpets are hung. Han progress and minority tradition. |

|

| The monastery from the outer kora. The monks' quarters look nice and tidy from here, but I believe they lack any plumbing or sewer, and only recently received electricity. |

|

| Because I'm an ignorant fool, I ended up doing the outer kora in the wrong direction. Actually, I didn't even know it was the kora—or what the kora was—when I started out. I just saw a path and I took it. |

|

| The only western tour group I saw outside of China proper. It looked like a decent budget tour with young people and a burly Tibetan guide who almost looked Sikh. |

|

| At the western end of the monastery the kora opens into some ruined foundations and a large latse looking over the valley. |

|

| In some ways I'm lucky I'm an idiot, because otherwise I probably wouldn't be looking in this direction. |

|

| So many khatags that the prayer flags are overwhelmed. |

|

| Views like this are difficult to beat. |

|

| View from below, as one who does the kora properly would see things. |

|

| I'll admit that the latse looks pretty good this way, too. |

|

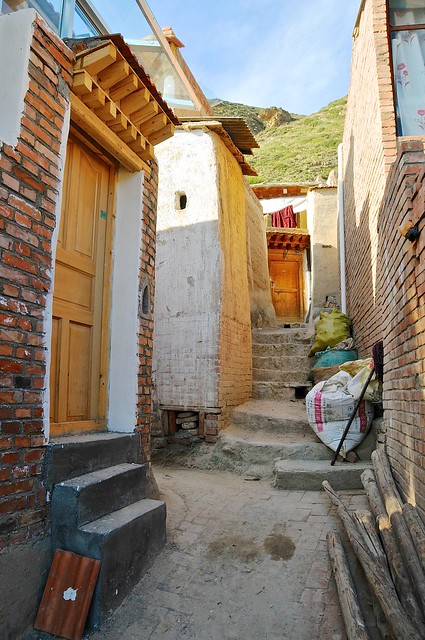

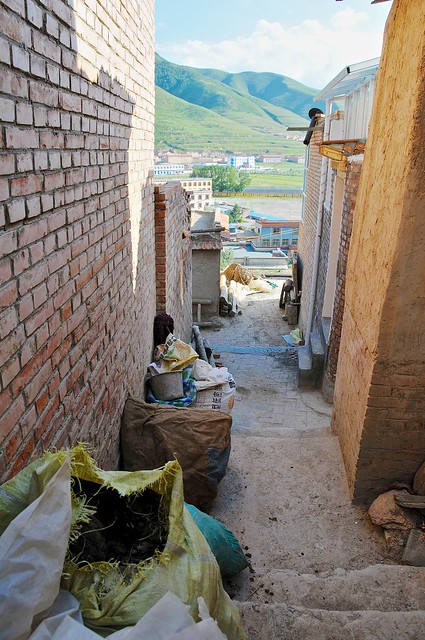

| More monks' quarters. They just build up her at will, building new houses and dwellings that climb higher up the valley. |

|

| Chimney from a house on a lower terrace level. |

|

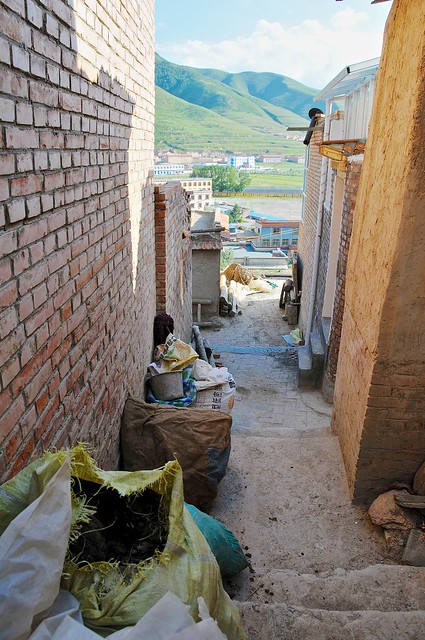

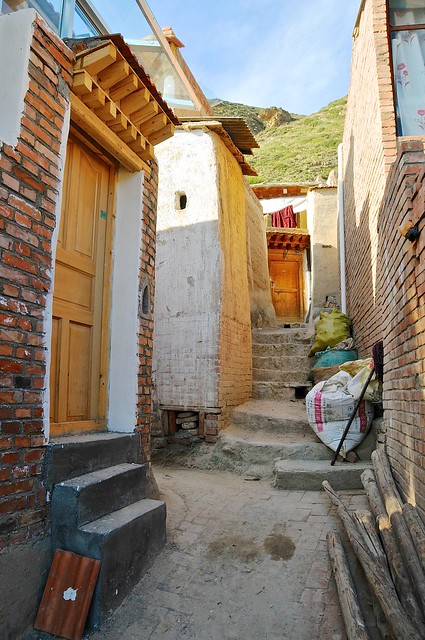

| The streets are charming but totally ad hoc. |

|

| These bags are full of fuel: yak dung. |

|

| Kids on their way home from school pass novices on their way to the monastery. |

|

| I had hoped to get a picture of this doorway with the novices walking by. They wanted none of it, and gave me the finger. |

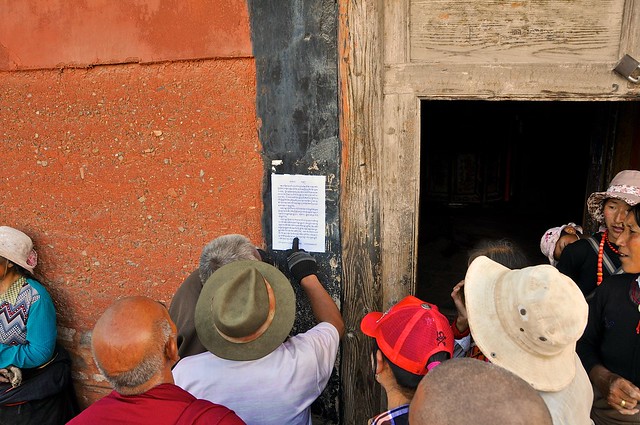

I was honestly a little surprised at how averse, in my experience, Tibetans were to sharing their culture or being photographed. (For most of the pictures I took that included people, I tried to shoot from hip level and be as unobtrusive as possible.) The experience with the kids was probably the most surprising, but in general it seemed like Tibetans didn't want to be photographed and didn't want to share much of their spirituality. This seems like a really strange position to take when they are also trying to raise international awareness, engaging in publicity-raising activities like self-immolation, and especially when they make an effort in Dharamsala—the seat of the Tibetan government in exile—to make religion and Tibet as accessible to foreigners as possible. And to be honest, the rather distant feeling I got from Tibetans was totally the opposite of the feeling I got from Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

I know that other people have gotten a very different impression from the Tibetans they met, but for the most part I felt they were decidedly cool, and not nearly as warm as I would have hoped (and possibly expected given their nomadic roots).

|

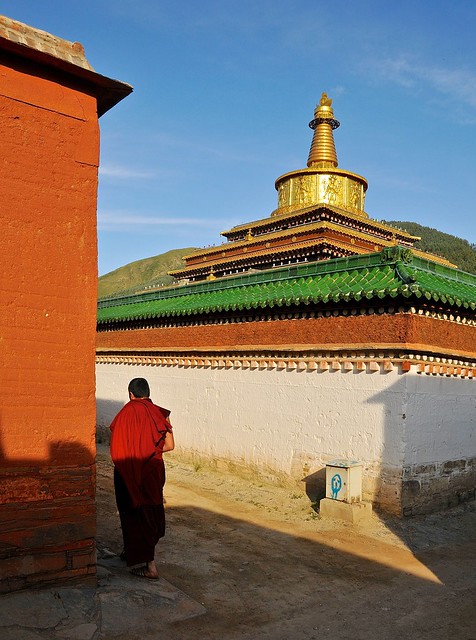

| Prayer wheels in front of the golden stupa. |

|

| Part of the inner kora. |

|

| Rooftop grasses throw shadows on opposing walls. |

|

| The decorative grasses seem to grow directly from the wall. |

|

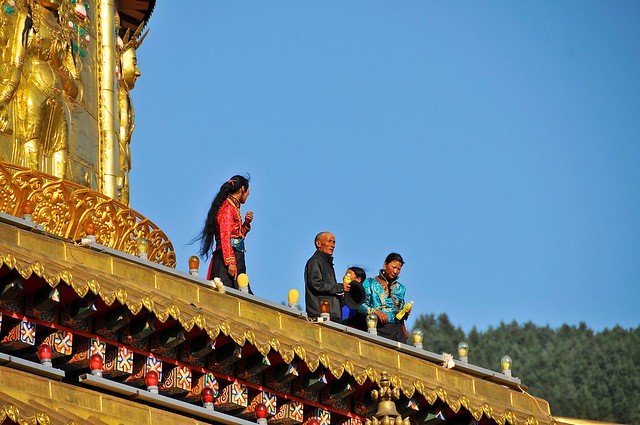

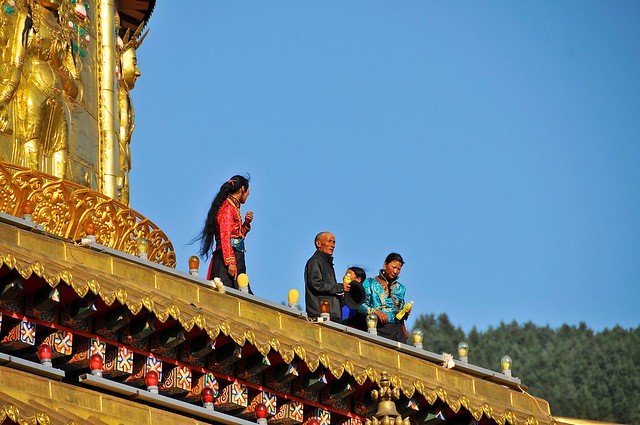

| Tibetans in silk finery at the golden stupa. |

|

| This monk popped out of one of the dwellings, went around the corner, then squatted in the street to pee under his robes. Then he went back inside. |

|

| The golden stupa in the evening light. |

|

| A monk heads toward the assembly hall. |

|

| A dead cat. I had seen this cat when I was at the Redrock hostel, and it seemed aloof at the time and didn't want any food. Possibly it was just suffering. |

|

| Tibetans excitedly read something posted on the walls of Labrang. I would be interested in knowing what it said. |

Xiahe was spectacular, and it proved to be a great place to meet other travelers. All of the hostels are within a few hundred meters of each other, and you're likely to run into the same people walking around or at a restaurant. Add in great weather, and it was a wonderful place to stay—and it was much easier to justify staying for three days in Xiahe than three days in Xian, even if there aren't as many sights to see. The only real challenge is in escaping Lanzhou, but if you're passing through Lanzhou it would be almost criminal not to head up to Xiahe even if only for a day.

Budget since leaving Mongolia

I started keeping an accurate tally of my expenditures after I left Mongolia. I was a little sloppy in the first few days, so my daily food and incidentals are pooled and averaged over the first week.

July 30 and 31 in Hohhot: 405 yuan; 203/night

- Bus from Erenhot to Hohhot: 95 yuan

- Anda Guesthouse: 60 yuan

- Food and drink: 80 yuan

- Train to Pingyao: 170 yuan

August 1 and 2 in Pingyao: 385 yuan; 193/day

- Harmony Hostel: 50 yuan

- Temple: 50 yuan

- Soft sleeper to Xian: 205 yuan

- Food and drink: 80 yuan

August 3, 4, and 5 in Xian: 565 yuan; 188/day

- 2 nights in Han Tang Hotel: 100 yuan

- Terracotta warriors: 150 yuan

- City buses in Xian: 20 yuan

- Hard sleeper to Lanzhou: 175 yuan

- Food and drink: 120 yuan

August 6 in Xiahe: 195 yuan

- Bus from Lanzhou to Xiahe: 75 yuan

- Redrock hostel: 40 yuan

- Laundry: 20 yuan

- City buses in Lanzhou: 3 yuan

- Dinner and drinks: 52 yuan

August 7 in Xiahe: 89 yuan

- Internet: 5 yuan

- Food and drink: 34 yuan

- Tibetan Overseas Hotel: 50 yuan

August 8 in Xiahe: 64 yuan

- Food and drink: 14 yuan

- Tibetan Overseas Hotel: 50 yuan

No comments:

Post a Comment