The overnight train to

Bukhara arrives at about 6:30 in the morning, and since it had left Samarkand at around 1:30, I hadn't been able to get too much sleep. But it's nice to be forced to get up that early in the morning, as it really lets you see the city before people and tourists are up and about.

The Bukhara train station really isn't in Bukhara but in the neighbouring town of Kogon, and is about 15km from the center of Bukhara. But they have regular marshrutkas/buses that run from the station, and if you just follow all the locals leaving the train you'll find them in a lot in front of the station pretty easily. The buses (or at least the one I was on) don't go into the center of historical Bukhara, but skirt the old town, eventually passing by the Ark on their way to the main market west of the Ark. Apparently there are some marshrutkas that go directly to the Lyabi Hauz area, however.

Before you leave the train station area, however, I suggest you take a couple of minutes to check out the nearby

Kogon Palace, apparently built for Tsar Nicholas II, who never arrived to see it. It just in front of the train station, across from the parking lot where the buses and marshrutkas leave from, but it's tucked a bit behind a park so you might not see it immediately.

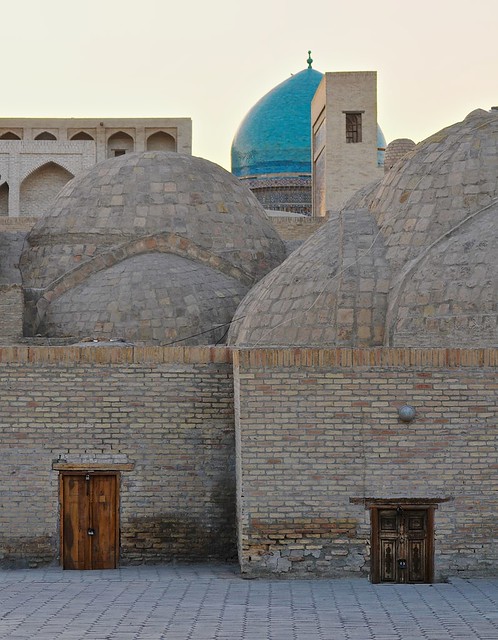

|

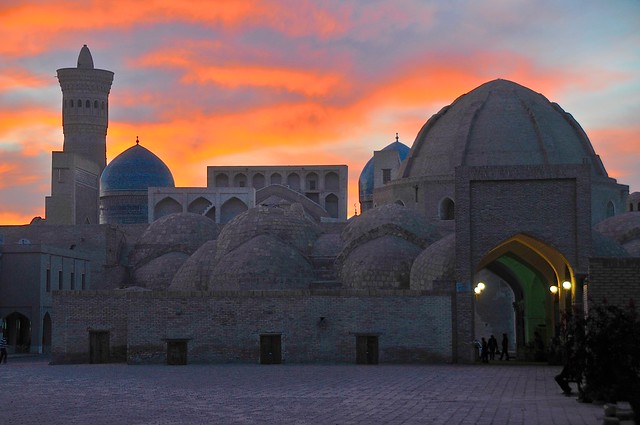

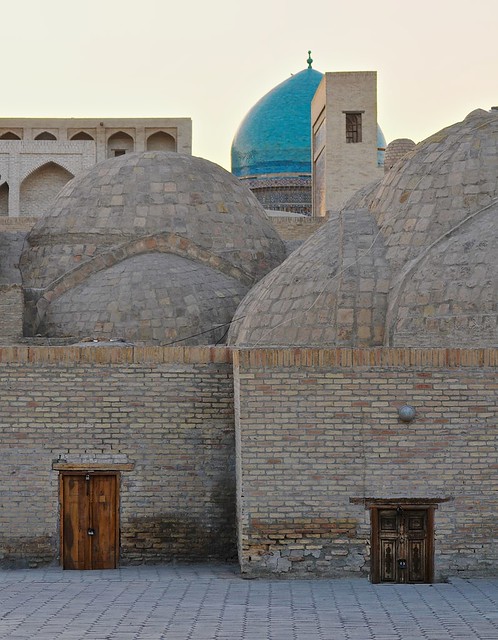

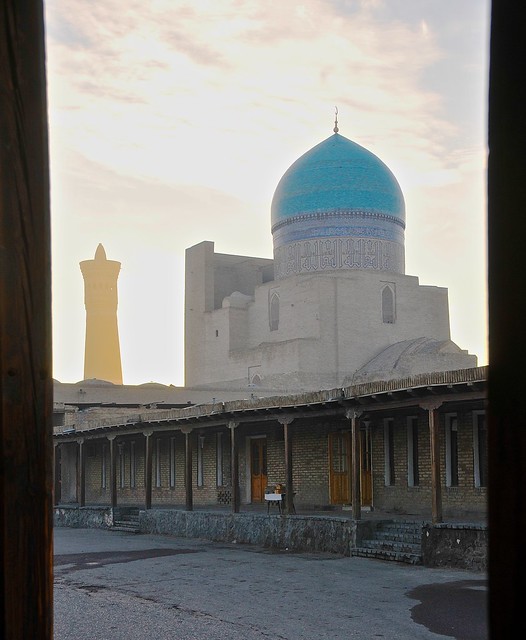

| Sunrise from the adjacent to the walls of the Ark, shortly after getting off the bus. The Ark was closed for restoration while I was there, and most of the walls that you can see have been pretty heavily restored already. |

|

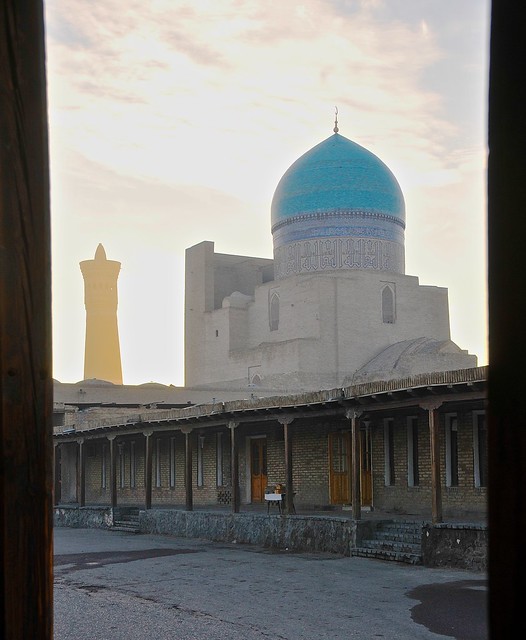

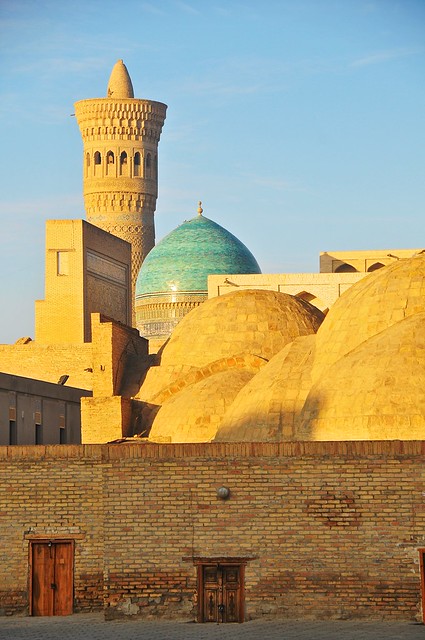

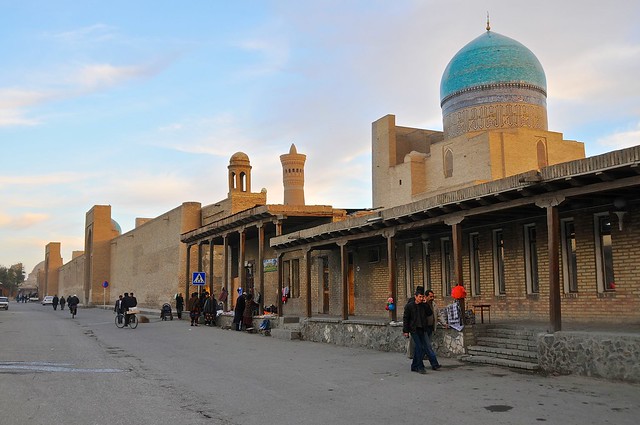

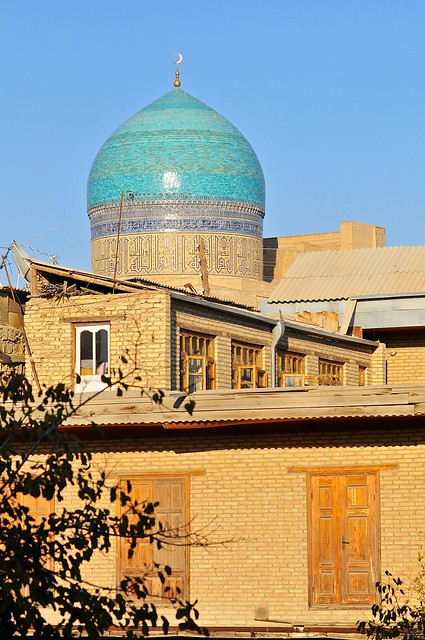

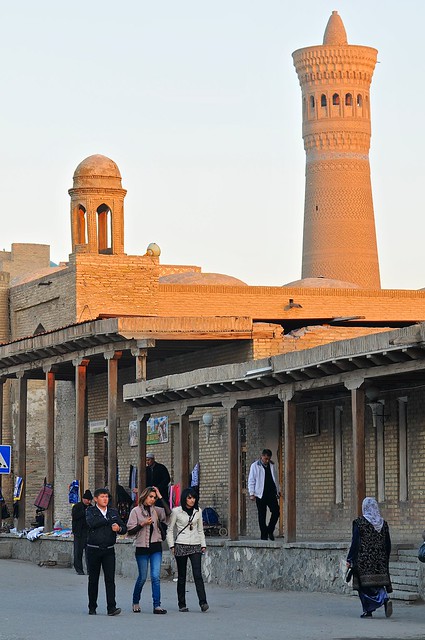

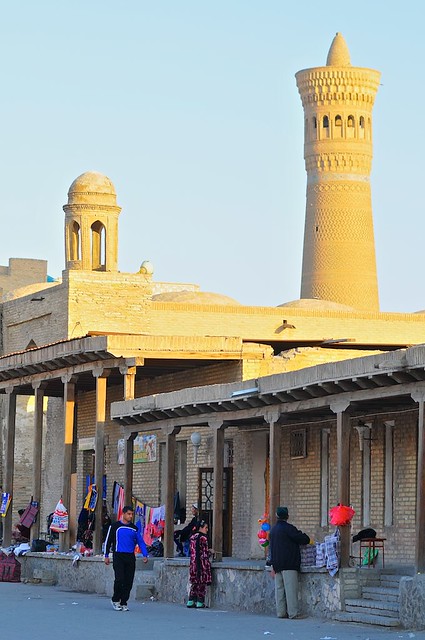

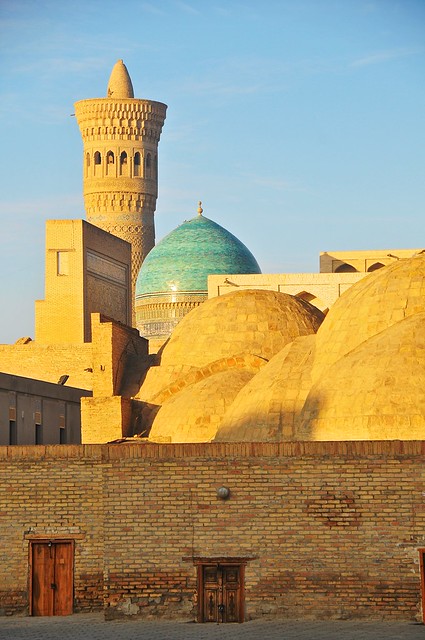

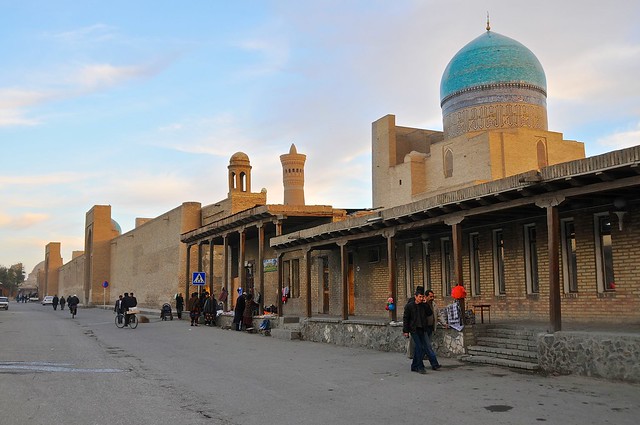

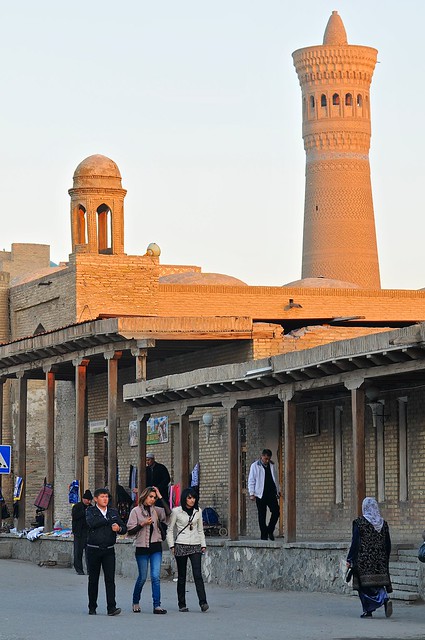

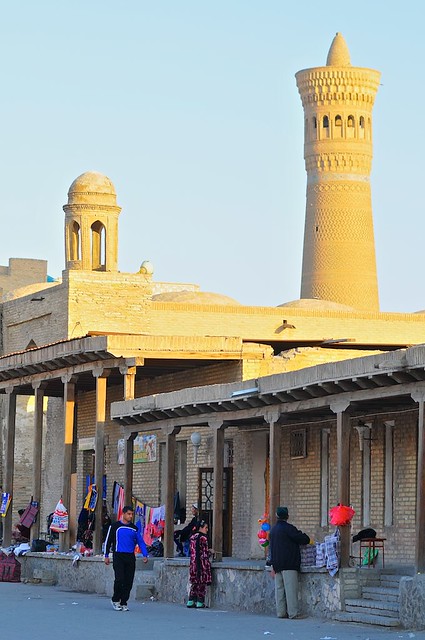

| The Kalon minaret behind the Kalon mosque, itself behind a row of shops. |

|

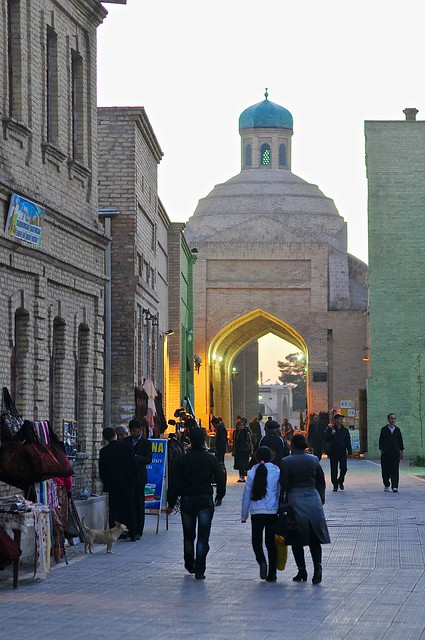

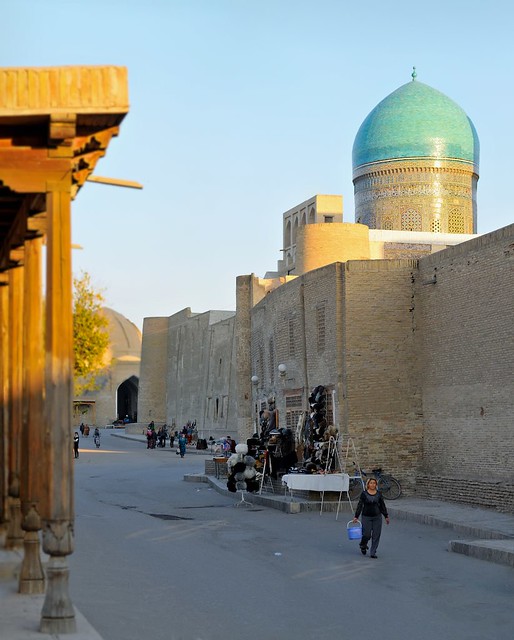

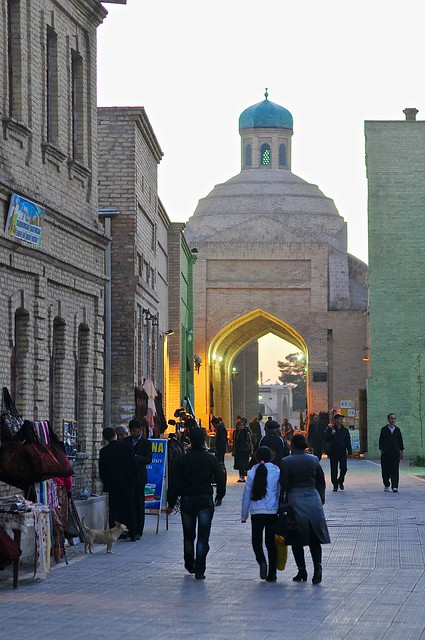

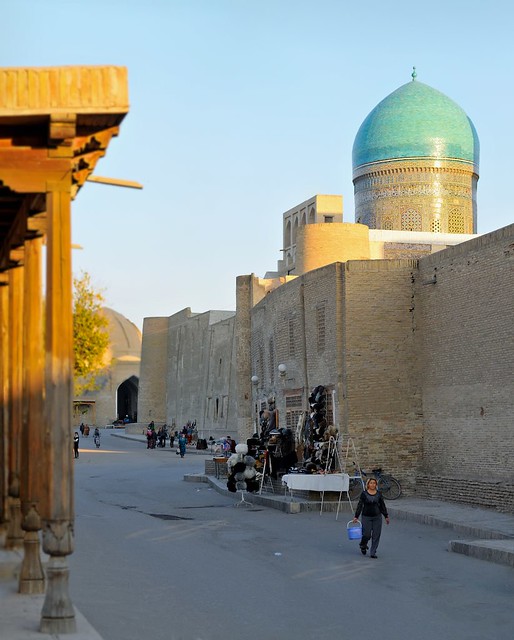

| View down the street that runs from the Kalon ensemble to the Ark. To me, Bukhara is immediately more likeable since the old city really feels old, worn, and lived in. Nothing feels glossy or new, and it has much less of a touristy vibe for some reason. I suspect the largely monochrome look of many of the monuments, and the way the blend in with residential buildings and shops, helps contribute to this. |

|

| The courtyard between the Kalon mosque complex and the (still functional, non-tourist) Mir-i-Arab madressa in the middle of the picture contains Bukhara's emblemaic Kalon minaret. Yet the shops around it are remarkably low key. |

|

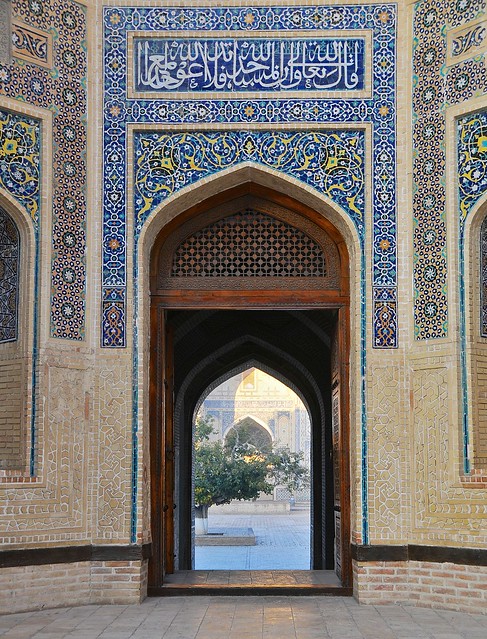

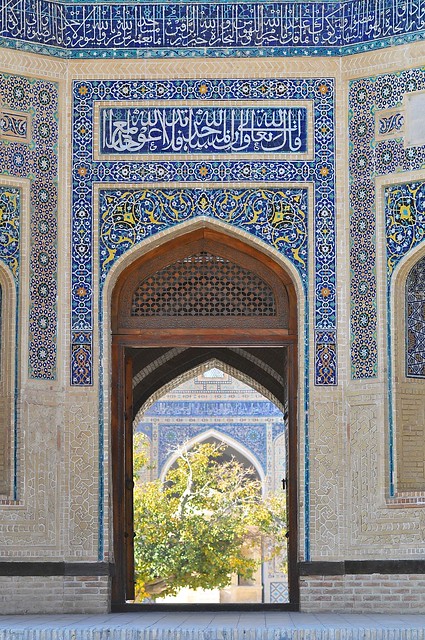

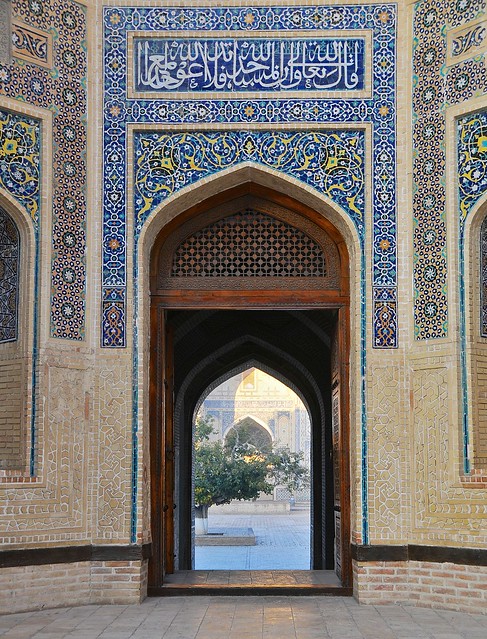

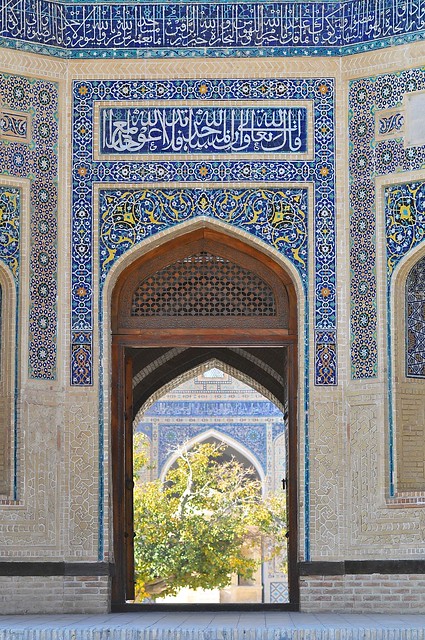

| The eastern entrance to the Kalon mosque complex. |

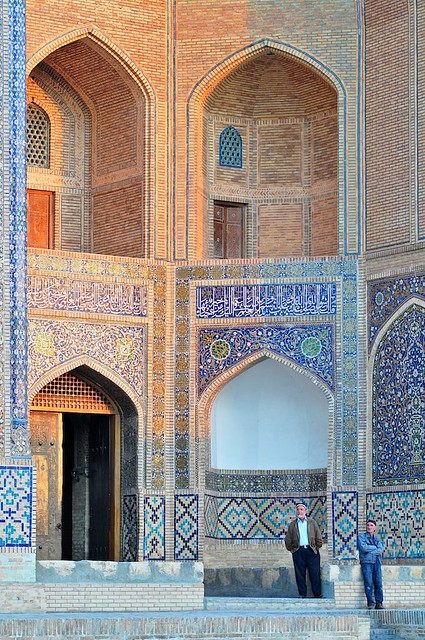

|

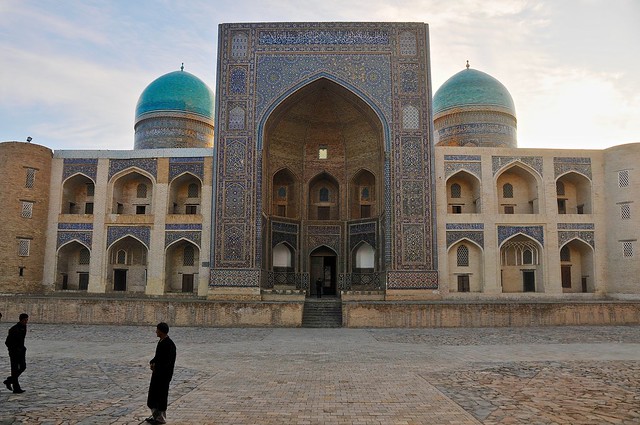

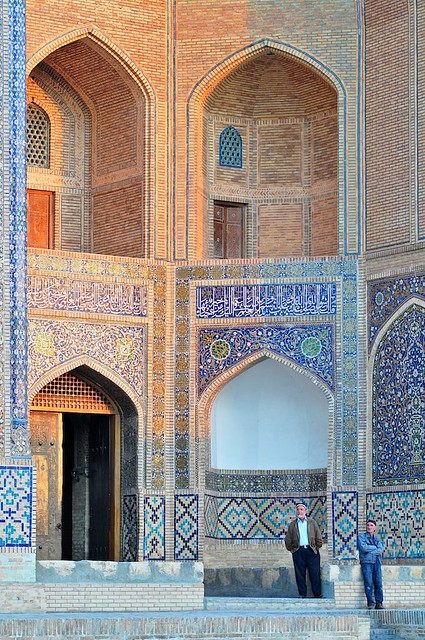

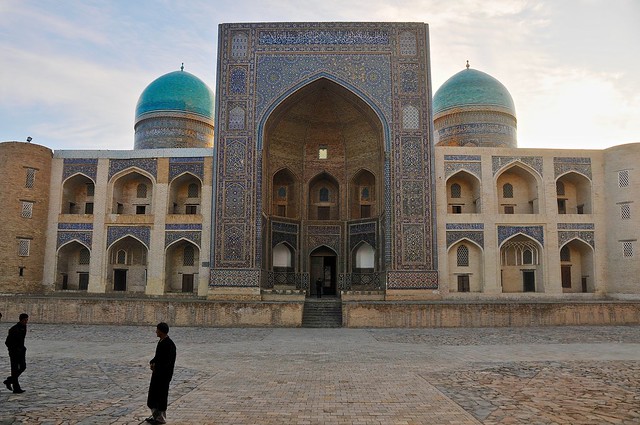

| View from the iwan towards the Mir-i-Arab madressa, with a couple of early-rising locals up and about. Tourists aren't allowed to enter the working madressa. |

|

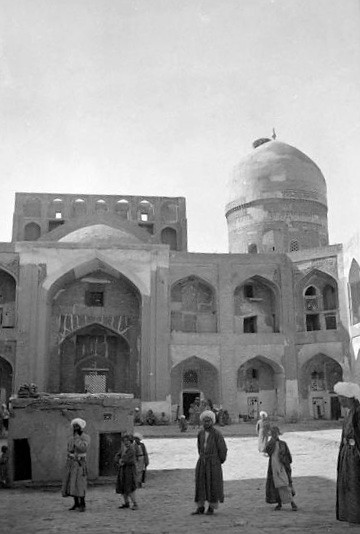

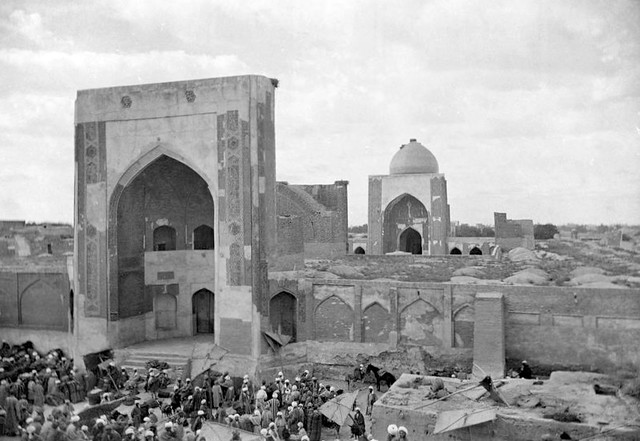

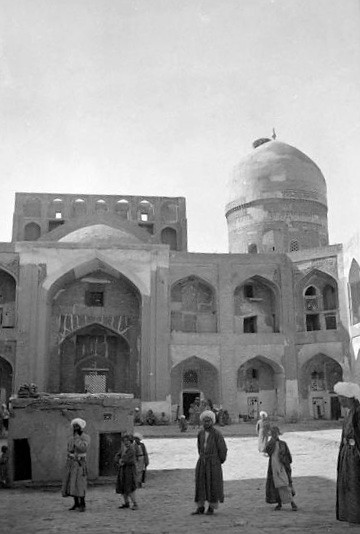

| View from inside the Mir-i-Arab madressa in 1890, courtesy French photographer Paul Nadar. |

|

| From under the iwan. |

|

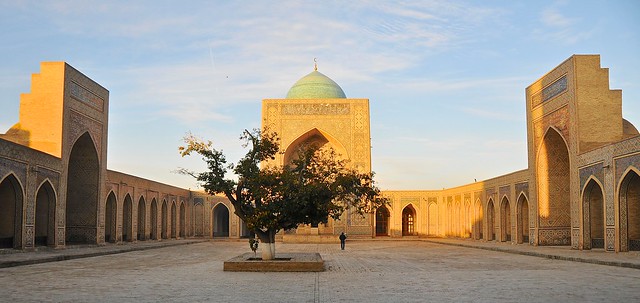

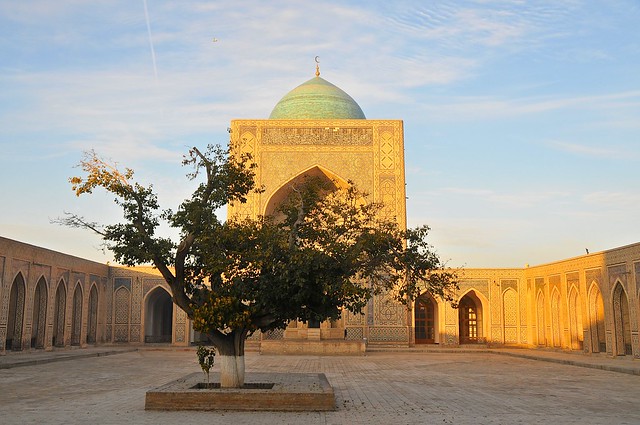

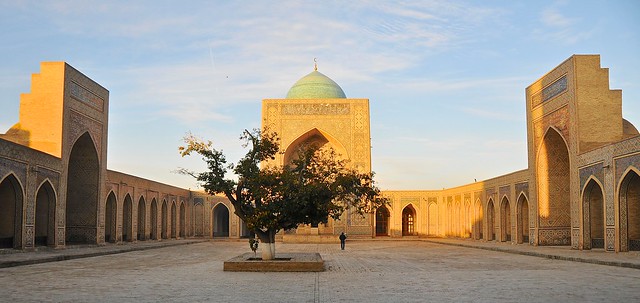

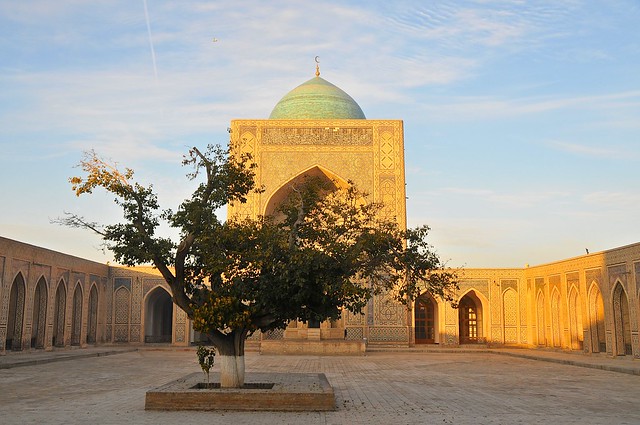

| Inside the Kalon mosque complex, which has a large courtyard anchored by the Kalon mosque at the western end. |

|

| The tree adds a a lot of character to the complex. |

|

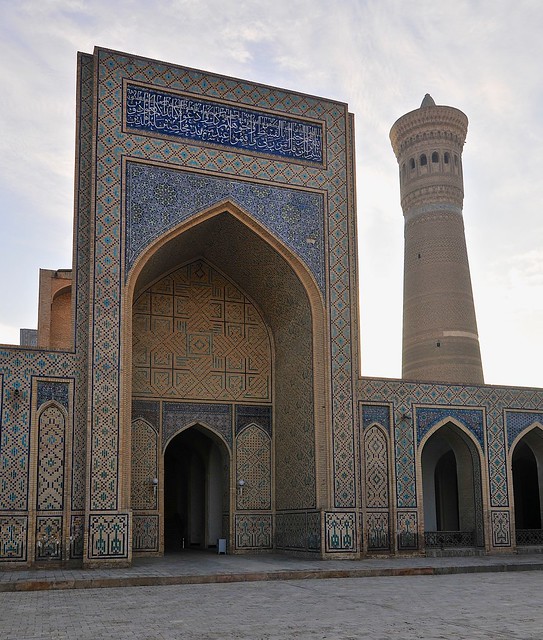

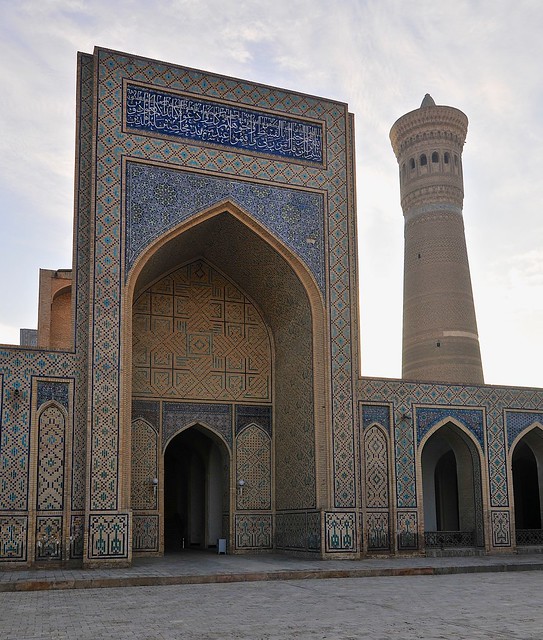

| The east entrance to the Kalon mosque complex with the Kalon minaret behind. Although the minaret is outside the mosque complex's walls, the entrance to the minaret is from inside the complex (but it's no longer possible to climb it). |

|

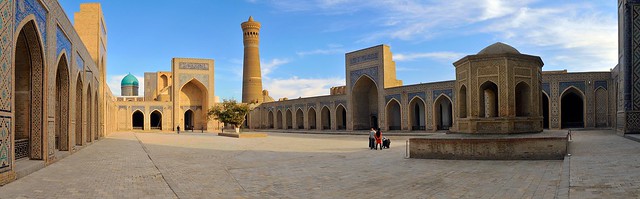

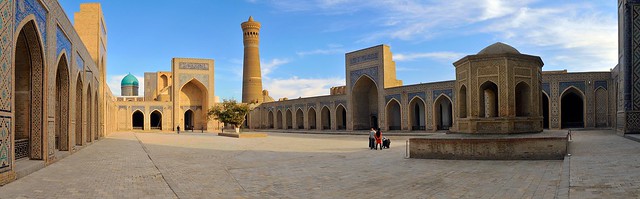

| Panorama of the mosque courtyard. On the right you can see an octagonal minbar, or pulpit, in front of the mosque's iwan and pishtaq. |

|

| View from next to the minbar. The minaret dates from 1127, while the mosque complex is from much later—about 1514. |

|

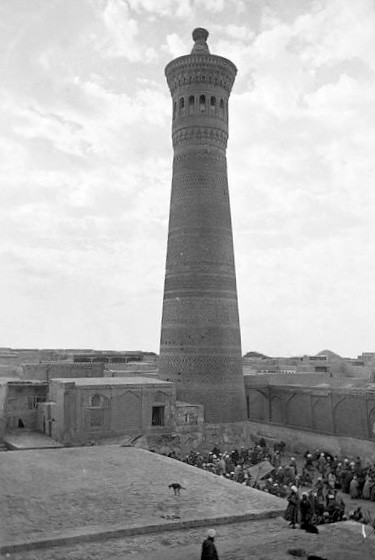

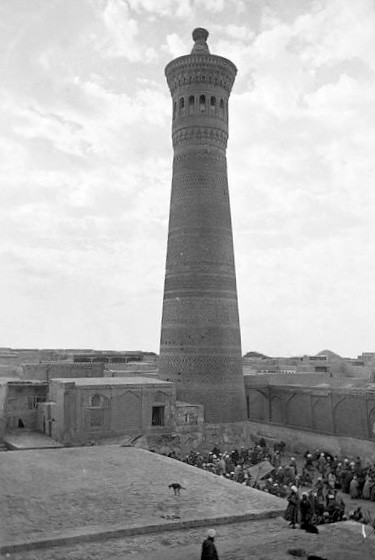

| The minaret from the Mir-i-Arab iwan. The bands of geometric brick patterning is reminiscent of the Sugong-Ta minaret in Turpan, and the narow band of blue tiles just below the viewing platform is apparently the first instance of this kind of coloration in Islamic architecture. |

|

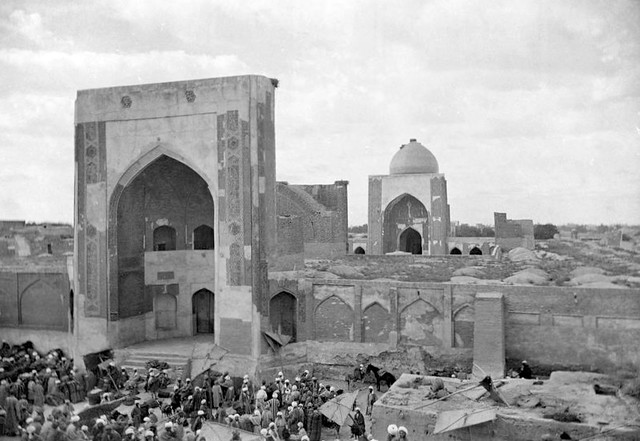

| View from a similar angle—but from the second story of the madressa—in 1890. |

|

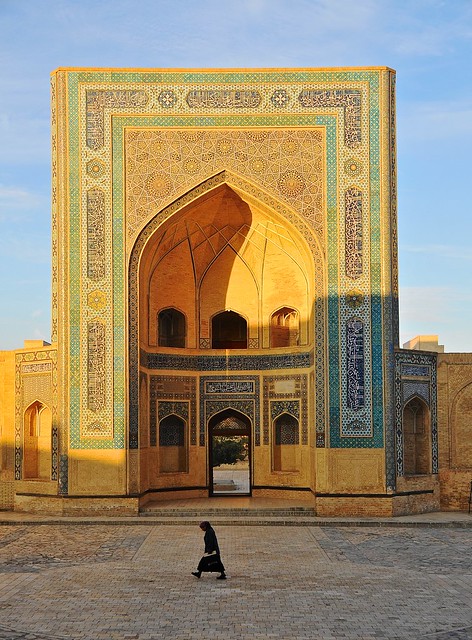

| The east iwan and pishtaq to the Kalon mosque courtyard. |

|

| In 1890 the pishtaq looked considerably rougher. |

|

| Looking up at the Kalon minaret. |

|

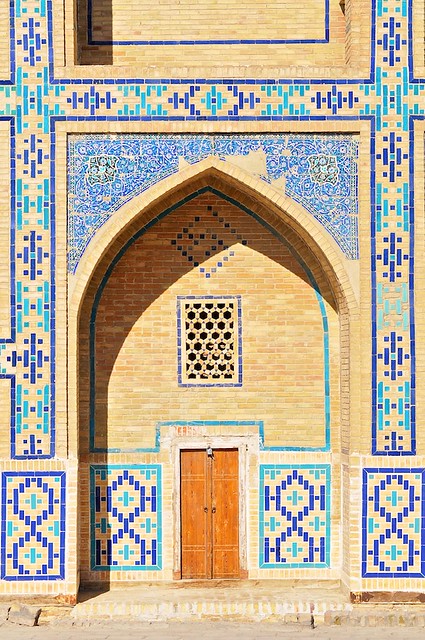

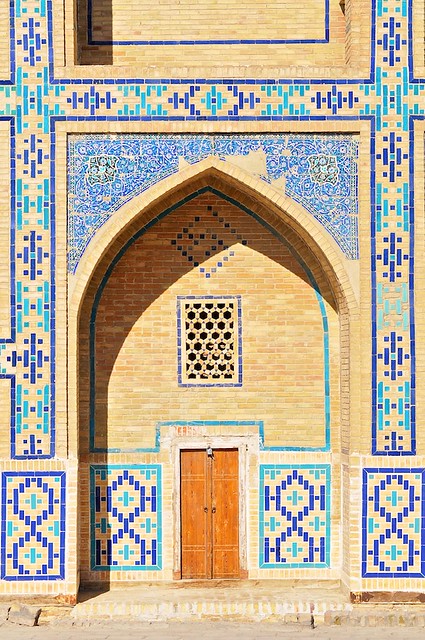

| The entrance to the Ulugh beg madressa. |

|

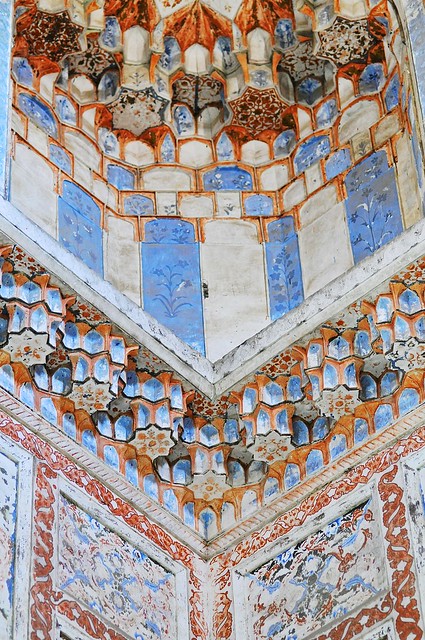

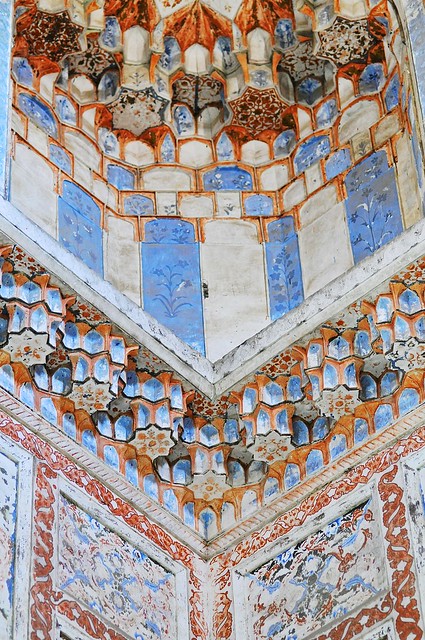

| The ornately decorated pishtaq to the Abdul Aziz Khan madressa, located opposite the Ulugh Beg, with multi-colour muqarnas decorating the roof of its iwans. |

|

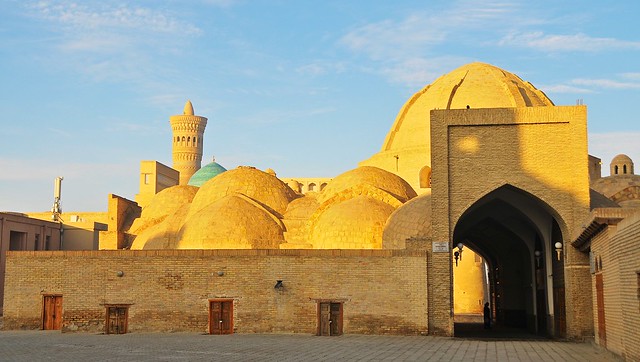

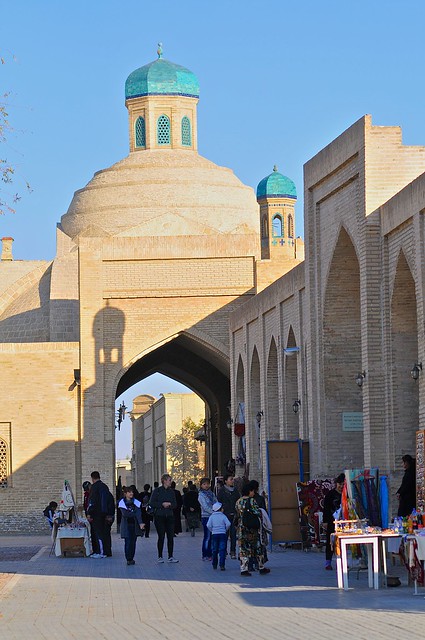

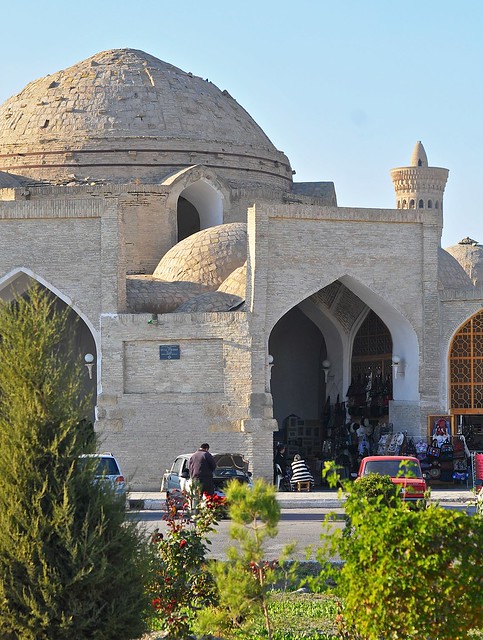

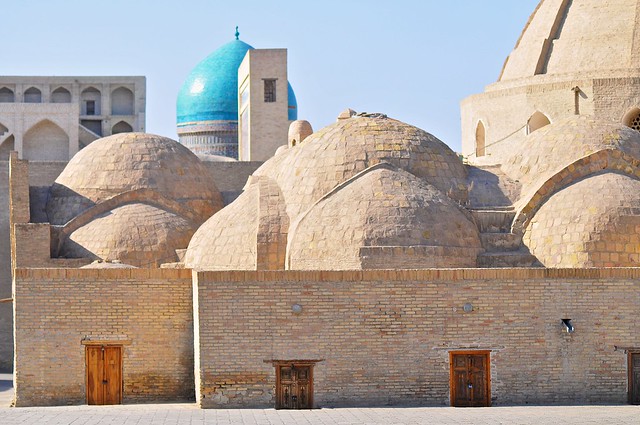

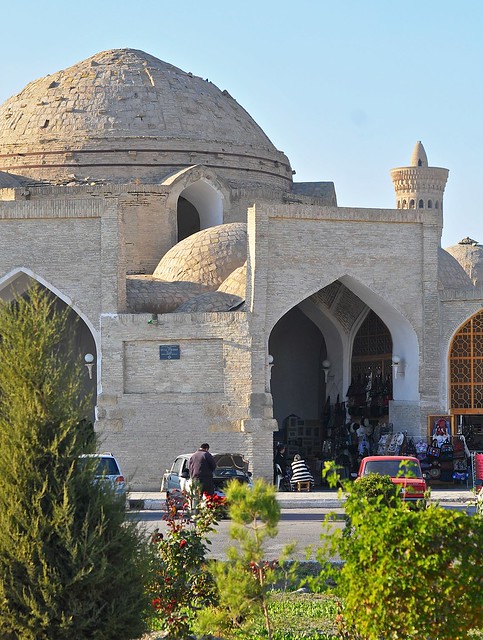

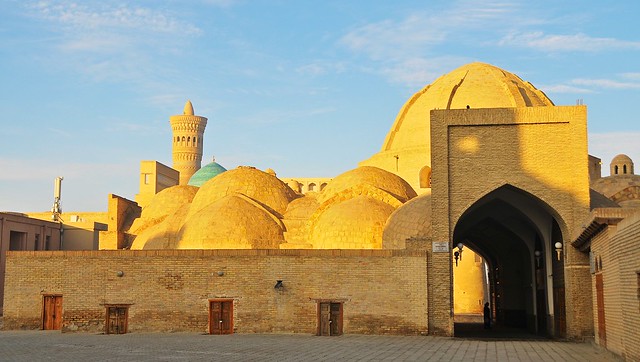

| Bukhara has a number of these domed buildings, which were—and remain—covered markets. These are where the main tourist shops are, and this one is the Taki-Zargaron bazaar that specialized in jewelery. |

|

| In Iran, markets are like this, except that you rarely see the domes

from the outside as they have miles of networked covered streets

comprising their markets. |

South of the center is the

Lyabi-Hauz area, which has a large pool of

water surrounded by madressas, restaurants, and tourist shops. This

makes it sound rather less atrractive than it is, as even the tourist

shops are pretty low key and unobtrusive. Most guesthouses and hotels are in the

residential sections around this area. Apparently Bukhara used to be full of such pools, which were breeding grounds of disease and insects, until the Soviets filled them in.

|

| The Nadir Divanbegi Khanaka, which was a Sufist gathering place, lies on the west side of the pool. |

|

| How it looked in 1911, complete with stork. |

|

| A dog makes his bed in a pile of leaves by the Lyabi Hauz pool. |

|

| This mostly-dead tree frames a view of the Khanaka. |

|

| The north side of the pool, just to the right, is occupied by a large chaikhana with gorgeous views. Not the little model of the Kalon minarety in the middle of the pool. |

|

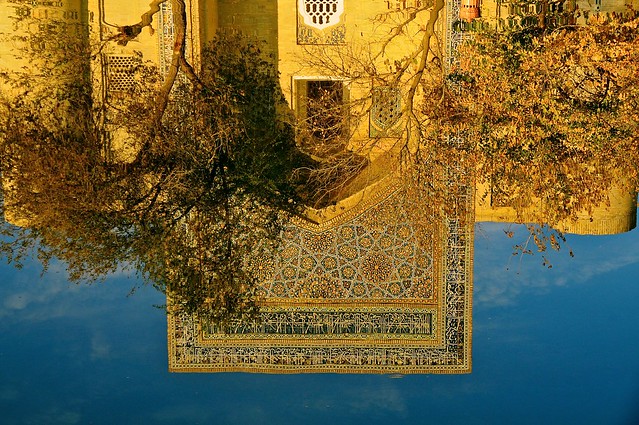

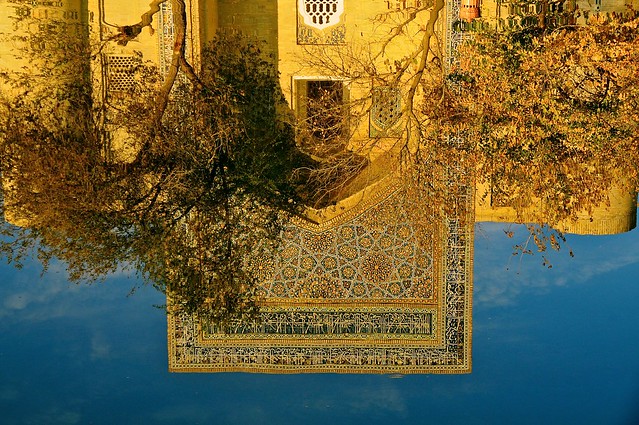

| Reflection in Lyabi Hauz. |

After looking around Lyabi Hauz, I started to look for a place to stay. One of the high-rated places in Lonely Planet was closed, while another didn't have the best vibe and wasn't open to negotiating their $10 rate for dorm rooms—since this is what I paid for a single with a bathroom in Samarkand, I figured I should be able to do better. I walked around south of Lyabi Hauz, and was looking at the entrance to one of the places listed in LP when a local approached me and helped me by poking his head inside the courtyard, seeing that no one was there, then took me a few houses down to another place where someone was up and about. This was just a helpful local, not a tout or commission-seeker, which was nice. They offered $15 for a single room, but when I said I had seen a place that was charging $10, we split the difference at $12.50. And for $12.50, this was probably the best deal I had had on a room so far: the hotel was maybe a year or so old, and it had a TV with English-language news and a sparkling bathroom with a western toilet and a bathtub. Needless to say, I used the shit out of that bathtub.

Like most hotels in the area, it was arranged like a madressa or caravanserai, with two stories of rooms arranged around the interior courtyard. Only a few rooms had windows that also faced the exterior, which wasn't a big deal as the streets are very narrow and you can't see much anyway.

By coincidence, it was US election day when I checked in, and when I turned on the TV and found a news channel, they were having a retrospective on Barack Obama and his accomplishments in office. For a while I thought the US had lost its mind and had relegated Obama to being a one-term President, but after a while it became clear the results were not yet in and that they were just talking about what he had done in his first term. Whew!

|

| To the east of the pool is a park, behind which is the Nadir Divanbegi madressa. |

After a bath and a nap, and then another bath to wake me up, I headed back out to the nearby Lyabi Hauz. On the east side, Nadir Divanbegi madressa was originally designed as a caravanserai, but was converted

into a madressa in the 17th century by Abdul Aziz khan.

Now, you might be wondering what a caravanserai is, and what one looks like. It's such an exotic sounding word, yet few guidebooks describe them except to say what their function was: a place of shelter for traders and travelers along the Silk Road. For the last couple of months I had been reading about caravanserais—especially Tash Rabat, which seems to be the only caravanserai east of here—but I still had no idea what to expect. And it wasn't really to Iran, where I saw a lot of caravanserais, that I learned what they look like. The short answer is that they typically look quite a bit like madressas: they have exterior walls around an interior courtyard, with rows of shops lining the courtyard. Sometimes they have interior passageways running around the perimeter, with shops on either side. While it seems like most madressas have two stories of study cells, many caravanserais have only one story, and they tend to have unadorned exteriors.

|

| A once-and-still caravanserai just south of the Lyabi Hauz pool. |

|

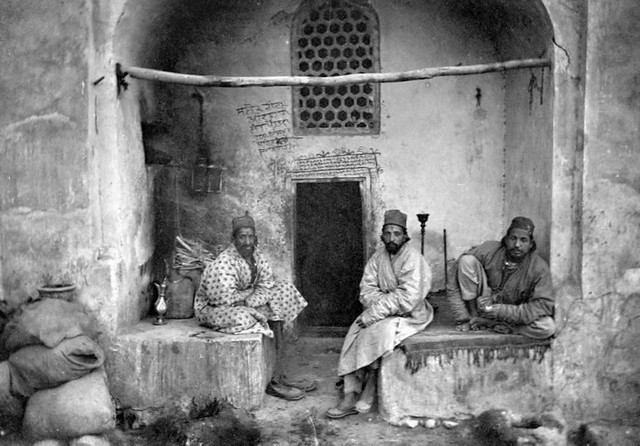

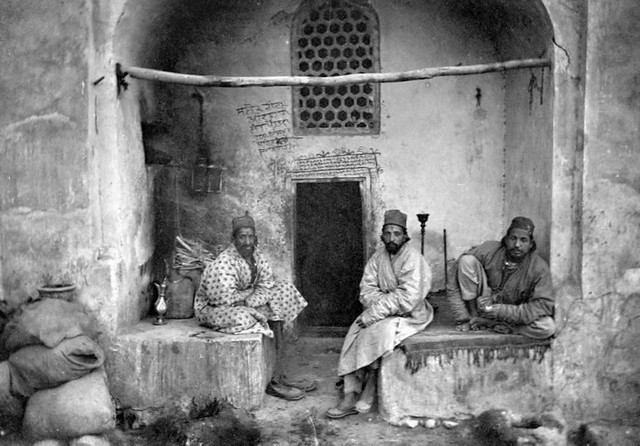

| A view of a caravenaserai store (or converted madressa cell) in 1890. |

|

| Under the dome of one of Bukhara's small covered markets, along the lines of the Taki-Zargaron bazaar seen above. |

|

| Random street scene in Bukhara. |

|

| A stork's nest decorates one of the minarets on the Abdul Aziz Khan madressa. |

|

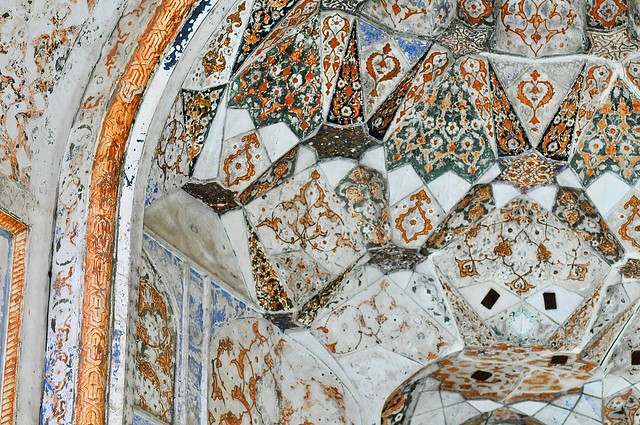

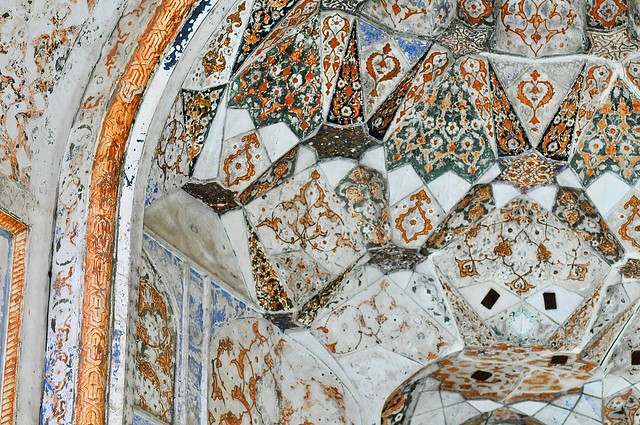

| The interior of the madressa. You can see patches where restored tiles have fallen off. |

|

| The crumbling muqarnas reveal the hollow-shell construction techniques, and plaster muqarnas. |

|

| Over at the Kalon mosque complex, under the domed colonnade surrounding the courtyard. |

|

| View between columns. |

|

| A view of the courtyard tree. |

|

| The northern iwan. |

|

| The minaret from next to the octagonal minbar. |

|

| For some reason the clearly restored interior walls aren't as objectionable as restorations in Samarkand are. Maybe it's because they feel modern and don't seem to be pretending to be anything they aren't. |

|

| View from the mosque area with its blue tiles to the eastern sections. |

|

| The octagonal minbar. This was used to duplicate prayers from inside the mosque proper to those praying in the courtyard. |

|

| The decorative bands and blue stripe on the minaret are clearly visible in the mid-day sun. The minaret was heavily damaged by the Russians when they took Bukhara in 1920. |

|

| The damaged minaret in 1920. |

|

| Madressa dome and pishtaq, then the outer and inner pishtaqs of the mosque complex. |

|

| Only a handful of Uzbeki tourists. |

|

| The main market is a few blocks west of the Ark. Here's a little dog checking me out next to an old Soviet car. |

|

| Next to the market is a section of the old city walls. |

|

| Some of the walls are less restored than others. |

|

| On the inside of the walls there are fewer signs of restoration, and locals use the green space adjacent to them to graze their animals. |

|

| There's a large pond next to the walls. |

|

| On the other side of the pond is a park with some monuments as well as a Ferris Wheel. |

|

| Everyone everywhere loves to fish. |

|

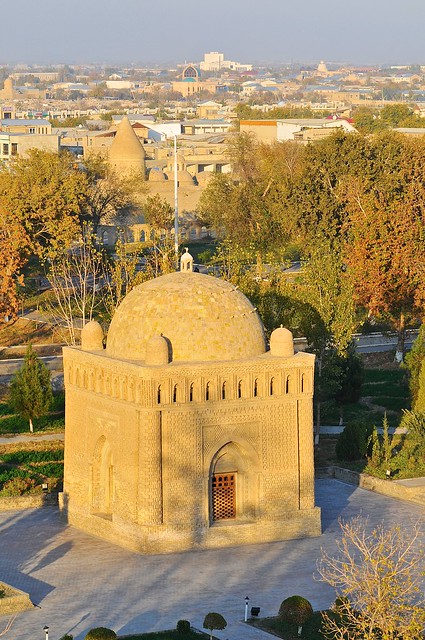

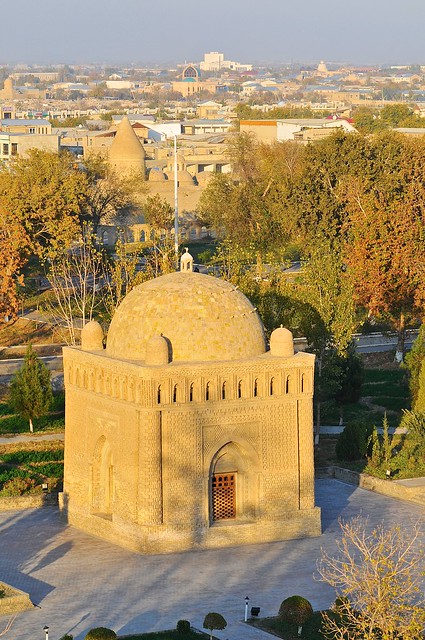

| This monochrome brick mausoleum is, with the exception of the domed roof, largely un-restored even though it dates from 892. The lighter colour on the lower section is, I believe, a result of the mausoleum being partially buried for a long period of time. |

|

| The spiky little roof dome. Like many, I believe this is one of the most charismatic and attractive buildings in Samarkand. In many ways the Masusoleums in Ozgen, in their monochromatic red, are deeply similar. |

|

| A pretty little cat guards one of the entrances, next to a donation. |

|

| The nearby Abdullah Khan and Modari Khan madressas are relatively anonymous and untouristed, and together they form the Kosh ("double") madressa ensemble. The Modari Khan is very simple monochrome brick on the inside, and in the high season contains the usual shops and restaurants—but was dead when I was there. The Abdullah Khan, on the other hand, has an interior of polychrome tiles, but is unusual in that the missing tilework has been filled in with monochrome backing, making it abundantly clear what is restored. |

|

| Back on the street by the Kalon mosque. Although there are a few souvenir vendors, most of the shops are selling things to locals. |

|

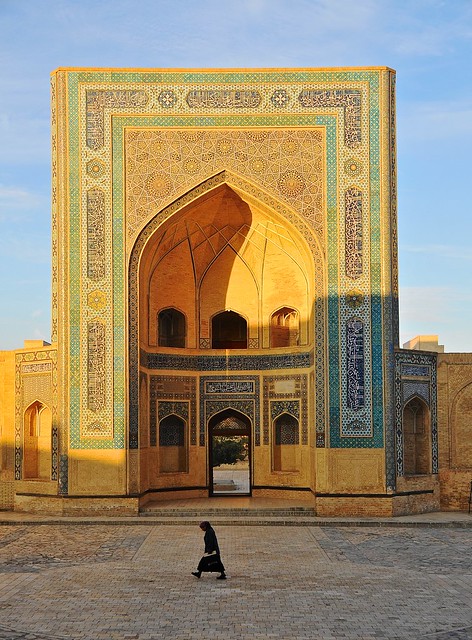

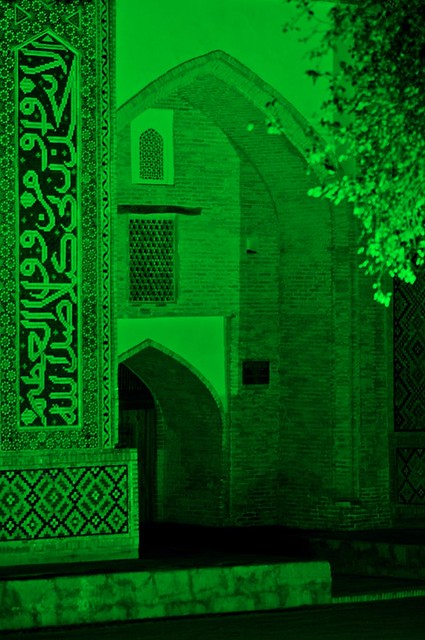

| The facade of the Mir-i-Arab madressa at sunset. |

|

| Looking more like Samarkand, with the turquoise tiles. I think I would prefer monochrome brick decoration. |

|

| Looking back over the Kalon mosque at sunset. |

|

| The Kalon minaret with the Mir-i-Arab madressa behind it. It's in credible just how red the buildings appear at sunset. The monochrome domes on the right belong to the Alim Khan madressa. |

|

| A wider view. You can see from the distance seaparating the outer and inner iwans of the Kalon mosque just how wide the surrounding arcade is. |

|

| On the south side the inner and outer iwans don't even line up with each other. |

|

| Another view of the minaret area. There were only a handful of tourists around to enjoy the views. |

|

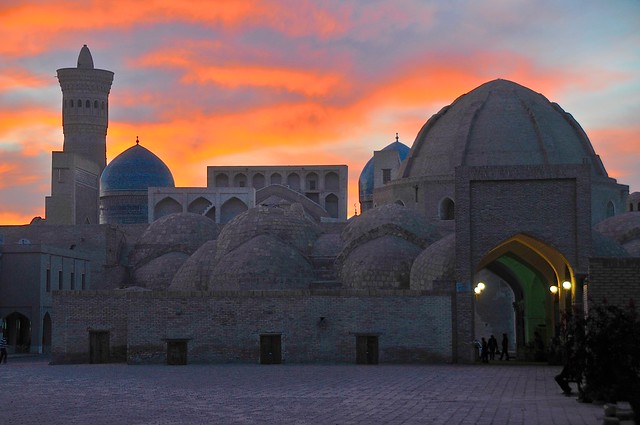

| Sunset over the Taki-Zargaron bazaar. |

As I was taking the above pictures of sunset, disaster struck: something inside my 18-200 lens broke, leaving me unable to zoom. For the past few days I had had difficulty zooming my lens, as it would feel very stiff during some sections, before releasing and letting me keep zooming. But whatever part was being stressed on the inside had finally snapped, and could be heard rattling around inside. I'm not sure when the damage was initially incurred, but after I got home and started to review my pictures at full size on computer that could handle doing so, it became apparent that something had been wrong with the lens for quite some time, as many pictures had been significantly softer on the left hand side for some time (something which was particularly apparent when stitiching together panoramas of the Pamirs, as the soft left-hand side of pictures are abruptly stitched to the much-sharper right-hand side of adjacent images). This meant that I was now left with only my 85mm lens to work with—a big problem given that this is effectively a 120mm lens on my D300's cropped sensor, and most of my pictures tend to be wide-angle. It's an even bigger problem given that there are few shops in Central Asia that carry DSLR lenses, and the majority of those that do only carry Canon equipment. I was to be without a wide-angle lens until I was able to find a replacement lens in Iran, which will limit the number and quality of pictures until then—no doubt a relief to those having to scroll past the plethora of pictures I'm spamming this blog with.

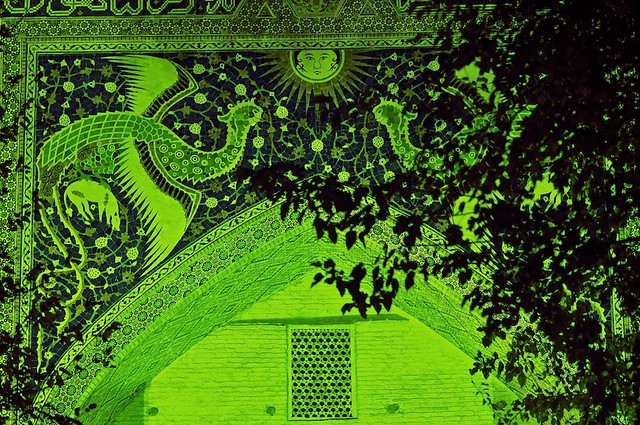

|

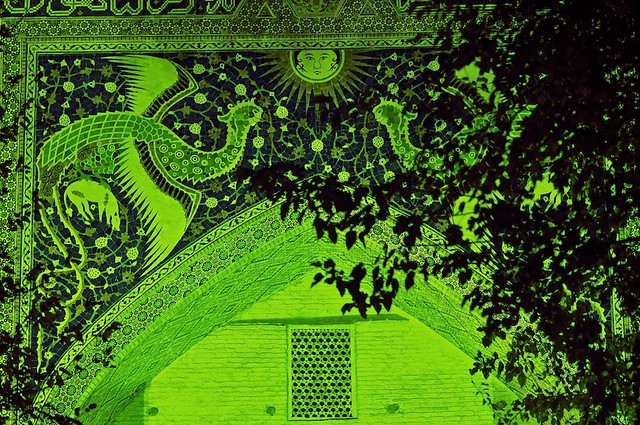

| Like the Sher-Dor madressa in Samarkand, the Nadir Divanbegi madressa on the Lyabi Hauz features the usually-forbidden depiction of living things. Here, a smiling sun, flanked by phoenixes and horses. |

|

| The left-hand phoenix and horse. |

|

| The whimsical Chor Minor. The name translates to "four minarets," even though they were apparently not intended to function as minarets, but as the decorative entrance to a no-longer-existing madressa. |

|

| In 1911 the area around Chor Minor was much more cramped. |

|

| With only an 85mm lens available, I was only able to get this picture by stitching together over 50 individual pictures. As I didn't lock focus before starting, however, on the full-resolution image you can see the focus changes in different areas of the picture. There's a souvenir shop on the entrance level, but upon ascending I found it to be wonderfully tranquil—I had the entire place to myself—and a great place to take in the city. |

|

| Looking west from Chor Minor, towards the Kalon complex. Unlike in Samarkand, they haven't tried to sanitize the city and wall off these residential sections from tourists' eyes. |

|

| The view south. |

|

| A few kilometers east of the old city is a park containing the Saifuddin Bukharzi Mazaar (Mausoleum) on the left and the smaller Bayan Kuli Khan Mazaar on the right. |

|

| These buildings have escaped over-restoration, and in the Bayan Kuli Khan Mazaar in particular you can see some original tile-work unobscured by modern imitations. |

|

| The spiky dome of the Saifuddin Bukharzi Mazaar. |

|

| Detail of the iwan tile-work on the Bayan Kuli Khan Mazaar. |

|

| These domes are almost as attractive, to me, as the smooth turquoise domes seen on more ornate buildings, and probably more attractive than the ribbed domes that typify the height of Timurid architecture. |

|

| Looking through the park. I suspect that even in the high season very few tourists go here, or to the nearby Fayzabad Khanaka, but they're definitely worth a visit. |

|

| There's a large market a block east of the mausoleum complex, and I bought some fruits and vegetables there. These stubby little carrots were delicious, and came in hues ranging from deep orange to pale yellow tinged with green. |

|

| The top of a tall and rather attractive Art-Deco-style Soviet building in Bukhara, next to the stadium, on the way from the market to the Jewish cemetery. |

|

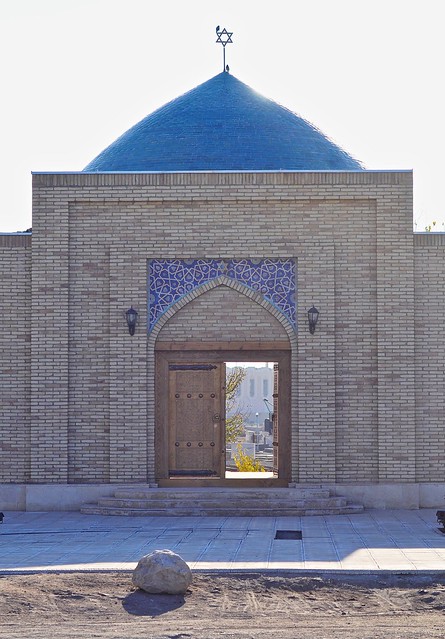

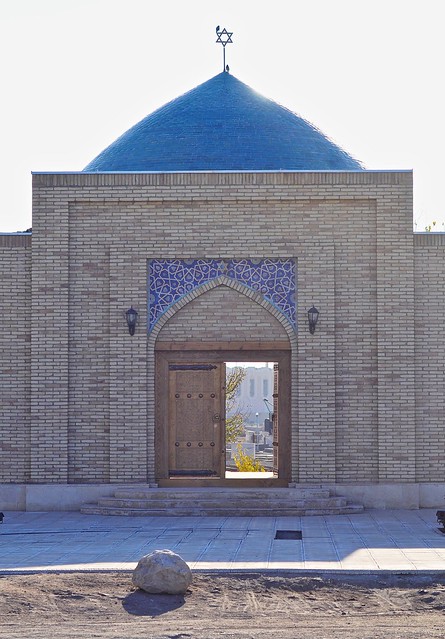

| The entrance to the Jewish cemetery is a rather typical looking portal topped with a Star of David instead of an Islamic crescent. |

Bukharan Jews is a term that is used to refer to pretty much all Central Asian Jews, and originates from the sizable population of Jews that was

centered in Bukhara from pre-Islamic times. The Jewish Quarter of Bukhara is pretty much everything between Lyabi Hauz and the cemetery a kilometer or so to the south, although post-Soviet emigration has resulted in a much smaller population of Jews today—

perhaps as few as 150.

|

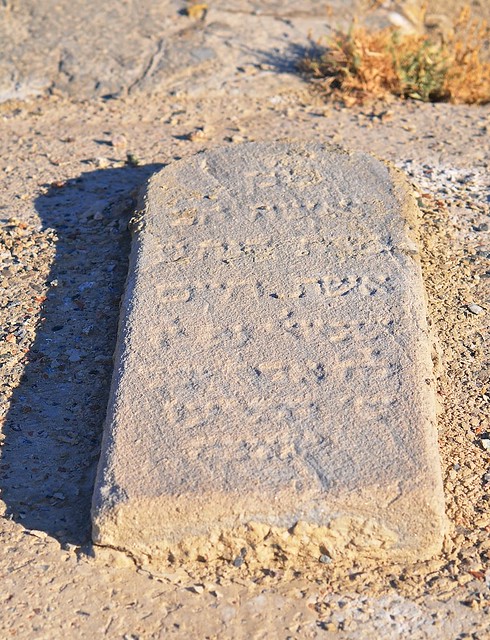

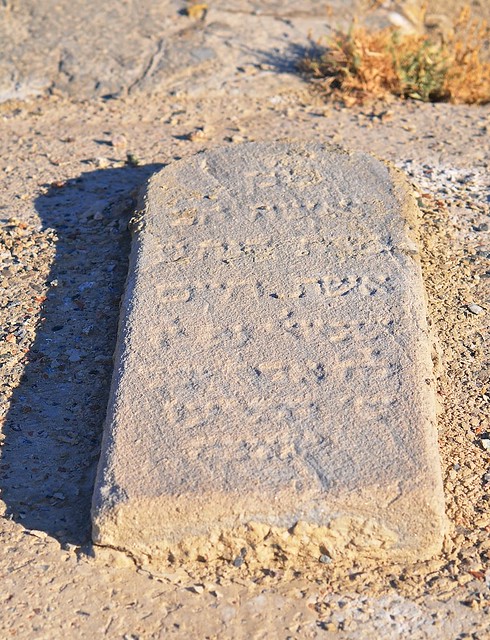

| Grave marker in the cemetery. |

|

| The condition of these markers is a testament to the age of the cemetery, which is mostly a baking-hot desert devoid of any vegetation except on the perimeter. |

|

| Barely-legible Hebrew. |

The walk from the cemetery back north through the Jewish Quarter to the center of Bukhara is quite pleasant, as it feels extremely untouristed and there are some old, unrestored mosques and madressas along the way, full of crumbling brick and collapsed walls. This gives a nice feel for just how old the city n its monuments are, and it's interesting to see that some of them are still places of religious significance and reverence.

|

| The Khoja Gaukushan Ensemble, a couple of blocks west of the Lyabi Hauz,

contains a mosque, madressa, hauz, and the Khoja Kalon minaret, which

is like a smaller version of the Kalon minaret (and without the blue

band at the top). |

|

| The Taki Saraffon trading dome is on the southwest corner of the Lyabi Hauz complex, and is full of tourist shops. It kind of looks like a Disneyland version of old Arabic architecture, with surprisingly little charm. |

|

| It looks like 95% of the bricks in these structures are new. Needs more dirt. |

|

| The gorgeous southern entrance of the Magok-i Attari mosque, reputedly Central Asia's oldest extant mosque. Monochrome brick work with only accents of turquiose tiles and a sympathetic restoration makes this incredibly attractive. |

|

| Mosque window through some branches. |

|

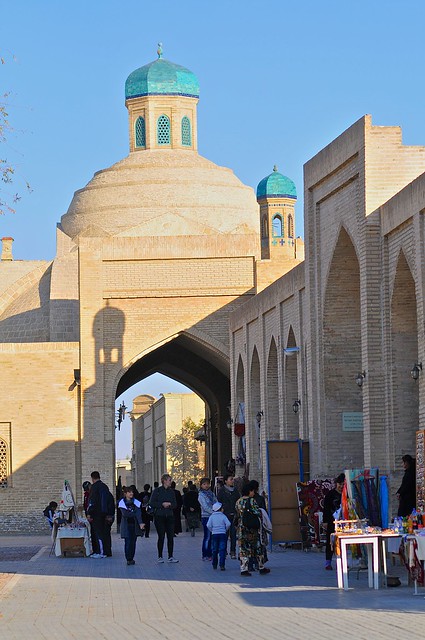

| Entrance to the Taki-Telpak Furushon trading dome from next to the old mosque. This is pretty much the epicenter of Bukhara's tourist trade, as the old market

is lined with souvenir and craft shops. But aside from the streets

leading north from the dome towards the Kalon minaret complex, and east

to the Lyabi Hauz complex, it's easy to get away from the souvenir shops

and forget they are there |

|

| Looking back from the madressa towards the dome. |

|

| North of the Mullo Tursunjon madressa, in a maze of back streets, is the Khoja Zaynuddin mosque, which contains a dry hauz and an air of decrepitude. Yet it also feels like a working mosque, and is very charismatic, making me really regret my broken lens. This is a view from the pool area over to the dome of the nearby Kalon mosque. |

|

| The all-too-imaculate walls of the Ark are obviously of recent reconstruction. |

|

| A cute dog comes to visit, and see if I'll give him some food. There are a surprising number of dogs kept as pets in Uzbekistan. |

|

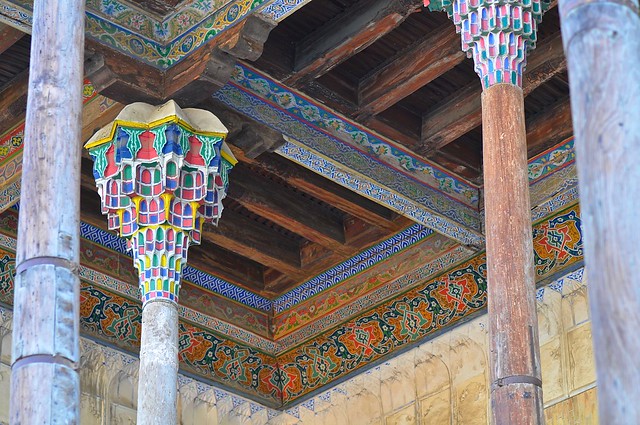

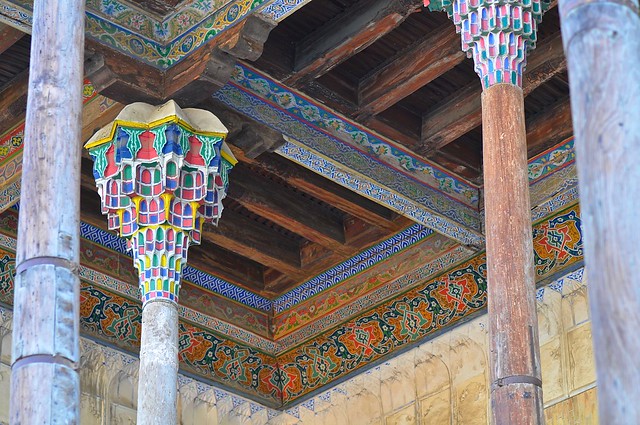

| The gorgeous and unusual Bolo Hauz mosque is across the ring road from the entrance to the Ark. As the name implies, it sits behind one of Bukhara's remaining hauz pools, and has the unusual design of having a tall open rectangular portico (technically an iwan, since it's closed on three sides) supported by wood columns topped with carved muqarna capitals and a richly-painted wooden roof. I arrived just as prayers were letting out. |

|

| Muqarnas and ceiling beams are all brightly decorated. |

|

| Near the Ismail Samani Mazaar is the Chashma-i-Ayub mausoleum, with an interesting conical dome. Such conical domes are characteristic of Khorezmian architecture, from the area around Khiva and Konye Urgench. I'm not sure if they are true domes—conical and bee-hive domes are frequently corbelled, and lack an apex keystone that you see in true domes. |

|

| There were some desperately poor kids begging near here—the only beggars I really saw anywhere on my trip. |

|

| Back at the Ismail Samani mausoleum. It has much more character when direct sunlight throws the brick patterns into relief, and glows orange in the evening sun. |

|

| The Kalon ensemble from the Ferris Wheel. |

|

| View from the Ferris Wheel, looking over the two mausoleums. |

|

| The entire park was pretty quiet. |

|

| View from the top. Not many people were on the Ferris Wheel. |

|

| The pond with the old city walls behind it. |

|

| The Ark gatehouse. |

|

| As it appeared in 1911. |

|

| Fiery bricks in the evening sun. |

|

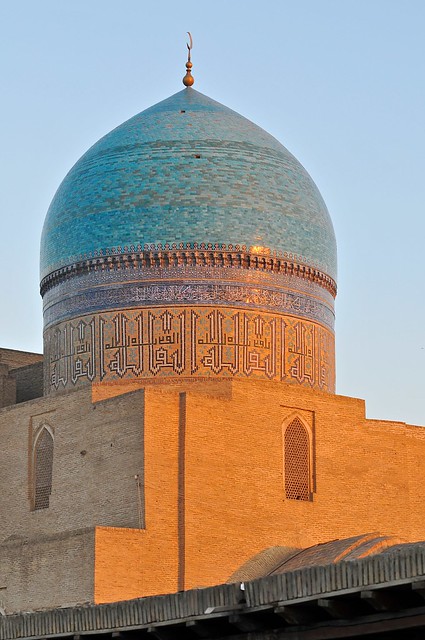

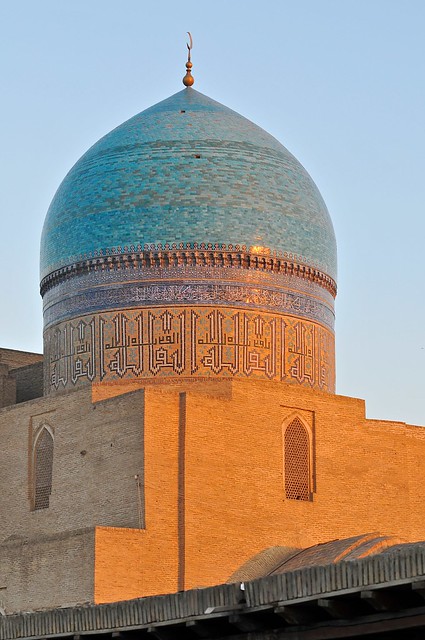

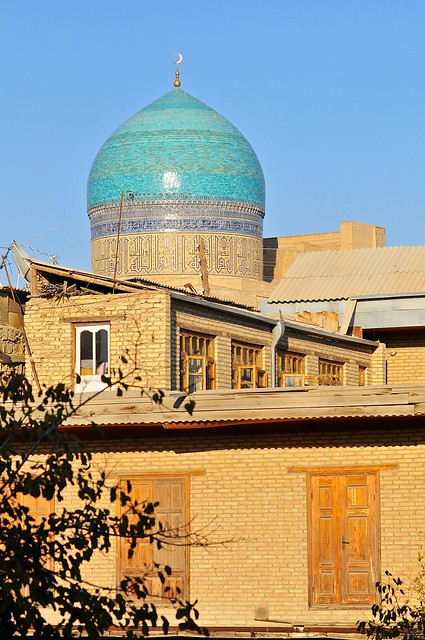

| The Kalon mosque dome. |

|

| Evening strollers. |

|

| A wedding party by Lyabi Hauz. |

|

| The Taki Saraffon domes from the southern edge of Lyabi Hauz square.The tourist shops that line the square and adjoining streets are mostly tasteful. |

|

| This section of the Ark's old un-restored wall shows just how much work has been done. |

|

| Looking into the Kalon mosque's courtyard. |

|

| The bread in Bukhara was probably the best since Xinjiang. In the mountains, in particular, it's difficult to find fresh bread, and much of the bread in other places is much thicker and meatier. The middle section of this Bukhara bread, in particular, is thin and crunchy, with little pockets of chewiness in the puffy square bits. I was eating a lot of bread and jam as on on-the-go snack. |

|

| The Kalon mosque's dome. |

|

| The domes of the MIr-i-Arab madressa and the entrance pishtaq. Note how all of the tiles other than at the very top of the clumun appear to be reconstructed. |

|

| The Lyabi Hau's chaikhana reflected in the pool, with the pishtaq of the Kulekdash madressa behind it. |

|

| If you read the Lonely Planet, you will see lots of references to ghanch, which they variously define as both plaster and alabaster, and use mainly to describe the muqarna stalactites used to decorate domes and iwans. In reality, ghanch refers to carved stone similar to alabaster. These muqarnas appear to be carved from ghanch, though most modern reconstructions are made from plaster as we've seen above. |

|

| These muqarnas are from the richly-decorated Abdul Aziz Khan madressa. |

|

| Looking up an iwan. |

|

| More gorgeous muqarnas, with sympathetic restoration. |

|

| More carved ghanch muqarnas, with their original paint. |

|

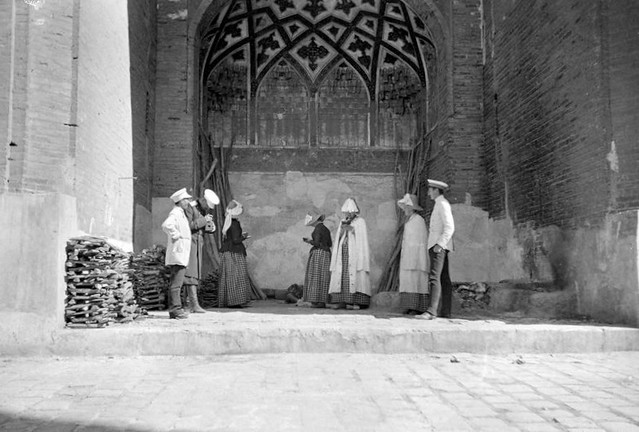

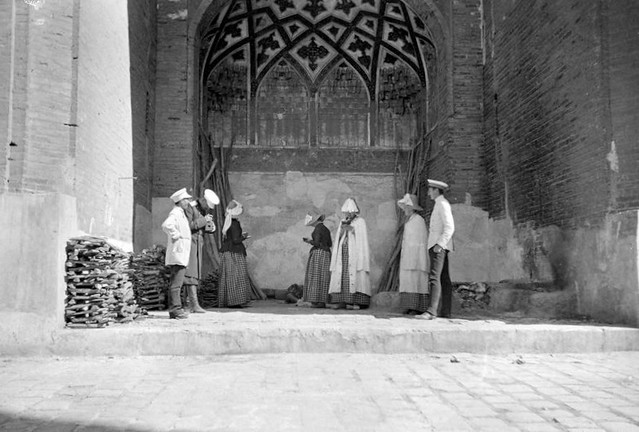

| Madressa iwan in 1890. |

|

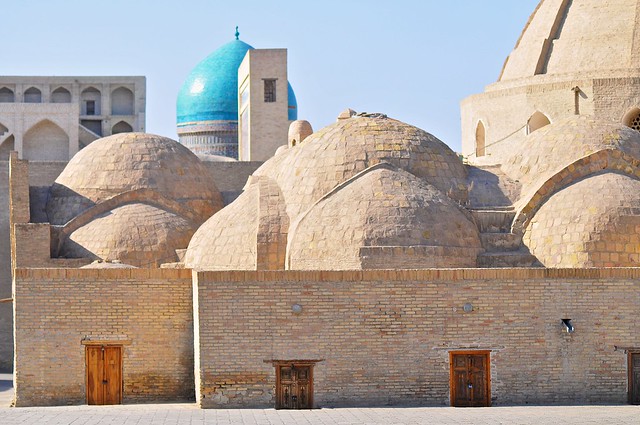

| View over market domes towards the back of the Mir-i-Arab, from between the Abdul Aziz Khan and Ulugh Beg madressa pair. |

|

| The Abdul Aziz Khan's entrance iwan has sxtremely bright colours that may reflect how it originally looked, but which appears bizarre given the age of the building. |

|

| Cell in Ulugh Beg madressa, located opposite the Abdul Aziz Khan madressa. |

|

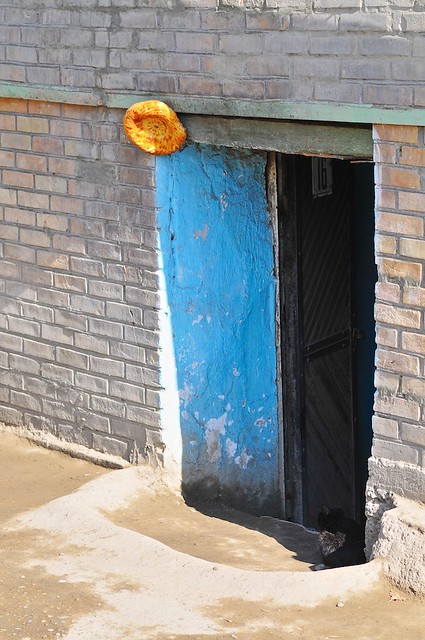

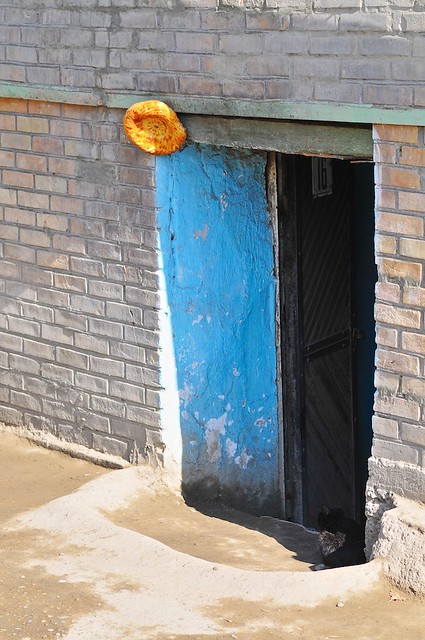

| Sometimes you're walking around town when you small freshly baking bread and you begin to salivate. Often the bakery is nothing more than a hole in the wall, helpfully signposted like this, with a naan stuck on a nail next to the door. Poke your head inside and buy one for 35¢ or so. |

|

| These doorway bakeries appear little changed from 1911. |

|

| As you walk around, you'll encounter old, crumbling, and unrestored mosques, madressas and caravanserais. Some are locked up, like this one, but some are not. |

|

| Even in the ones that are locked up, you can still get a sense of what lies behind. |

In the afternoon I went to take a look at the bazaar a few kilometers north of the old city, from where shared taxis to places like Urgench and Khiva leave. Part of my reason for doing this is because departure points often differ from what is listed in LP, and I wanted to make sure I would show up in the right place the next day. I confirmed cars to Urgench left from there, and was offered a ride from a somewhat desperate driver (most cars leave in the morning, so he really wanted to fill his car up) who kept dropping his price. At least I had an idea of how much to pay the next morning.

After exploring the market, I headed north to explore the

Sitora-i Mokhi-Khosa—the Emir's summer palace—built by the last Emir of Bukhara and largely dating from the early 20th century. The palace was built in Russian style, and was mostly furnished in western style, though it also contains a hauz pool next to the harem building (also built in a western style). While the building is interesting in itself, it's especially interesting to compare it with the buildings and street scenes depicted in Paul Nadar's 1890 pictures, which are roughly contemporaneous (indeed, one of Paul Nadar's more remarkable pictures is of Tashkent's train station, which seems extremely out of place given all the other scenes he memorialized). Unfortunately, these kinds of architectural views really aren't amenable to capturing with an 85mm lens, so I have no pictures.

|

| On the way to the summer palace I had my first-ever close-up view of cotton plants. They had been cut down and dumped in the middle of the street, their pods open and raw cotton billowing out. Uzbekistan is one of the world's largest producers of cotton, and the Soviet decision to turn the country into a cotton producer is largely responsible for the Aral Sea drying up (much water was—and is—diverted to feed the thirsty cotton plants). Today, Uzbekistan is notorious for the forced labour and slavery surrounding the cotton industry, as every year students and citizens are forced into the fields to bring in the crop. |

From the Ark to the summer palace, with a stop at the market/taxi point.

|

| Back in Bukhara, a view of the Ark's entrance, with guards in the front. |

|

| Another view from the Ark towards the Kalon ensemble. Those cars are parked at a small market tucked behind street-front shops, and they contain carpet sellers and other shops, mainly selling to the local market. |

|

| The market would be on the other side of this street, behind the store-front shops. In these shops they sell some things to the tourist market on the walkway, but the actual shops are more for locals. |

|

| Mosque corner. |

|

| A tourist shop set into the mosque compound's walls. |

|

| Kalon minaret and pishtaq. |

|

| The Abdul Aziz Khan madressa at sunset. Note the brightly-painted iwan muqarnas. |

|

| Rear entrance to bazaar shops. |

|

| The Mir-i-Arab madressa entrance at sunset. |

|

| The madressa's facade. |

|

| View over a the Alim Khan madressa, located just next to the minaret. |

|

| From the south it's easier to see where the minaret was damaged by Russian shelling, and what parts of it have been reconstructed. |

|

| View from next to the Alim Khan madressa. |

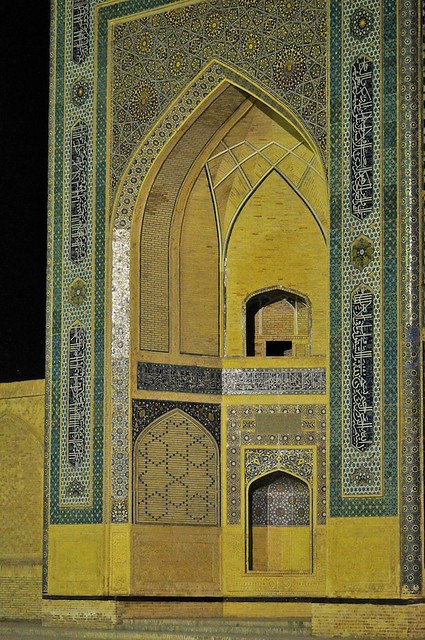

|

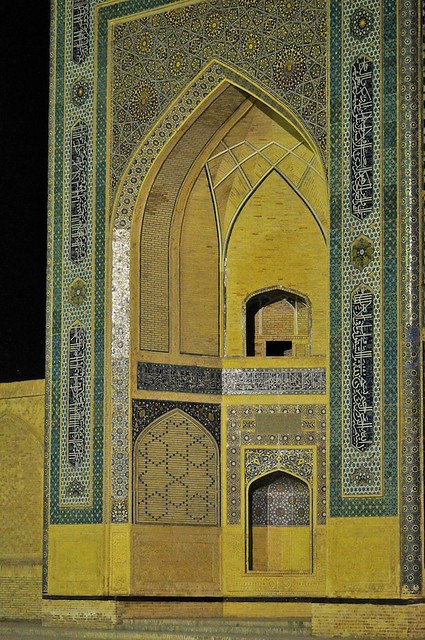

| Mir-i-Arab's iwan at night. |

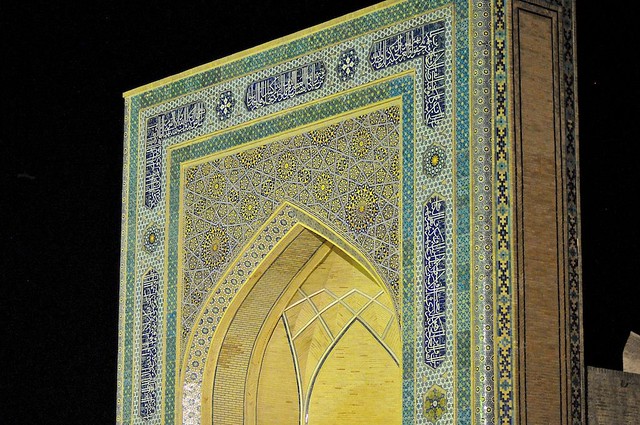

|

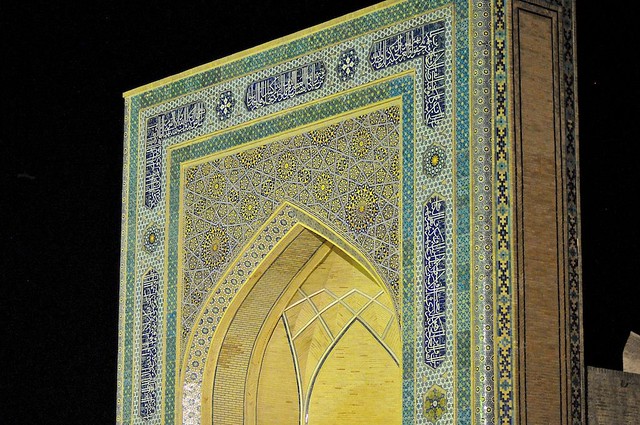

| Detail of the pishtaq top. |

|

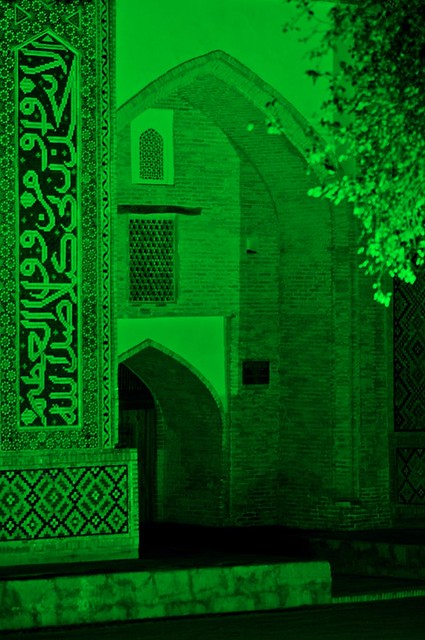

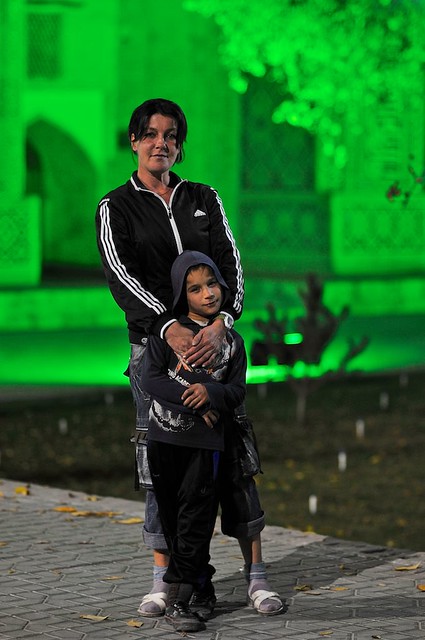

| At night the Lyabi Hauz monuments are bathed in green light. |

|

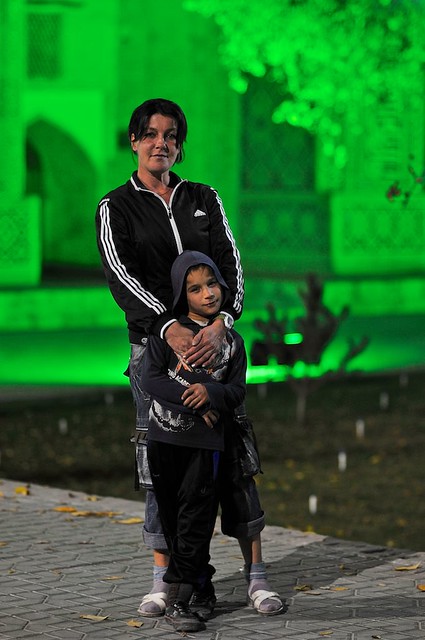

| This Russian lady wanted me to take pictures of her and her son. This was a bit weird, since Russians generally don't do this (nor do Uzbekis, for that matter). |

|

| After taking her picture she asked for money, which wasn't shocking. Her son wandered away when she asked. |

|

| The Nadir Divanbegi madressa's pishtaq mosaic. |

|

| The entrance of the Nadir Divanbegi Khanaka. |

|

| And reflected in the hauz. |

Paul Nadar's Bukhara photographs.

Budget

November 6: 2,500 som + $12.50

- Room: $12.50

- Bread x 2: 2,500

November 7: 26,000 som + $12.50

- Room: $12.50

- Bread, coffee, coke: 5,000 som

- Internet: 4,000 som

- Pears & carrots: 4,500 som

- Ferris wheel, ice cream, hot dog, bread: 4,400 som

- Dinner: 8,000 som

November 8: 30,000 som + $12.50

- Room: $12.50

- Bread: 900 som

- Jam & ice tea: 8,000 som

- Summer palace: 6,500 som

- Bus, bread: 1,500 som

- Hot dog, pastry: 3,000 som

- Ice tea: 2,000 som

No comments:

Post a Comment