The train arrives in Mary at around 2:00 in the morning, and we I pile off the train with a bunch of locals. It's quite cold, and at first I'm a little worried because no one exits through the station building, but from the ends of the platform. On the western edge of the station building is a small, semi-enclosed area full of vendors selling hot snacks, and I stop there to grab a fried pastry.

Thankfully, the station building was open, and there were lots of people milling about inside, presumably waiting for the next train. I find an empty bench and sit down and lean back to get some sleep, but a security guard approaches me. I figure he's going to tell me I can't sleep here (none of the locals seem to be asleep), but in reality he's just telling me to watch my stuff to make sure no one takes it. I'm a little surprised by his concern, but thankful.

It turns out that I could have taken an early-morning train to Bayram Ali, which is the town just south of the monuments at Merv, but since my plan was to exit to Iran via Serakhs the next day, I was planning on staying in Mary for the night, as it supposedly had a cheap hotel. A few hours later, when the sun was up, I set out to find the Hotel Caravanserai, which was described in the Lonely Planet. unfortunately, the map of Mary in the LP was almost as bad as not having a map at all, as it included streets that didn't exist, and pointed to the Hotel Caravanserai as being in the wrong location. I ended up wandering around some random streets until I ultimately got within a couple of blocks of where the hotel was supposed to be. When I though I was on the right street I asked some local shopkeepers where it was, but they hadn't even heard of it. Thankfully, a passerby heard my inquiries and told me they would take me there. It turned out to be on a small side street, less than 200 meters from the shops where I had been asking, but it had no sign on the outside and appeared to be just another house. Inside the compound, it was really arranged almost like a modern caravanserai, with rooms around around the perimeter of a courtyard (admittedly this is a pretty common layout in many places in the world).

I thanked the good Samaritan, and as I entered the hotel to try and find the receptionist or proprietor I was greeted by a couple of guys staying in one of the rooms by the entrance. They invited me to stay with them in their room, and they told me that I could stay with them for free. I later understood that this meant hiding me from the owner, and pretending that I wasn't there, which meant I had to sneak to the bathroom which was located further into the main courtyard. Well, that was fine with me. After dropping my stuff off and having a quick shower, I left to take a look around Mary and go to Merv.

How to get to the Hotel Caravanserai from the train station. There are reports that the hotel may be closed, but that may also just be local misinformation.

|

| The local workers (welders) who invited me to stay in their room in Mary. |

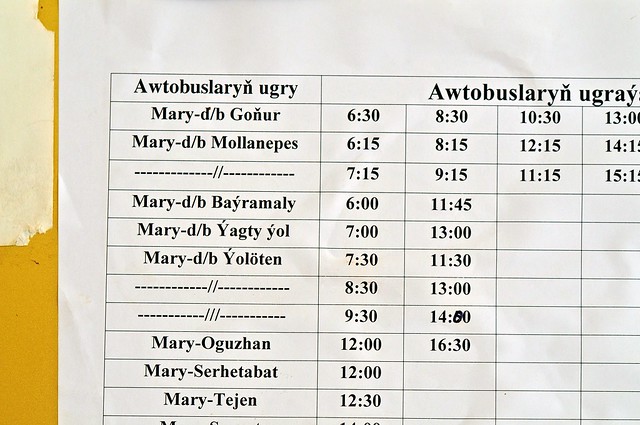

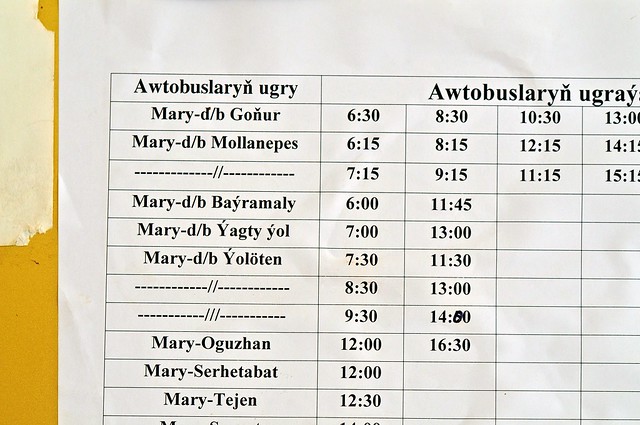

I didn't see too much of the town, but I found out from the bus station (just across from the train station) that there was a bus going to Bayram Ali at 11:45.

|

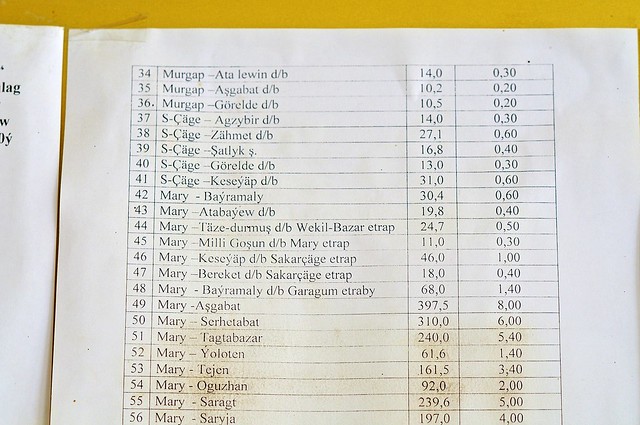

| Bus schedule from Mary. The 6:00 bus to Bayram Ali is convenient for those not staying in Mary (the local train at about the same time is probably even more convenient). Gonur is north of Bayram Ali, so those buses probably come close to Merv and may even pass near the entrance gate (but it's also possible they turn north before reaching Bayram Ali/Merv). |

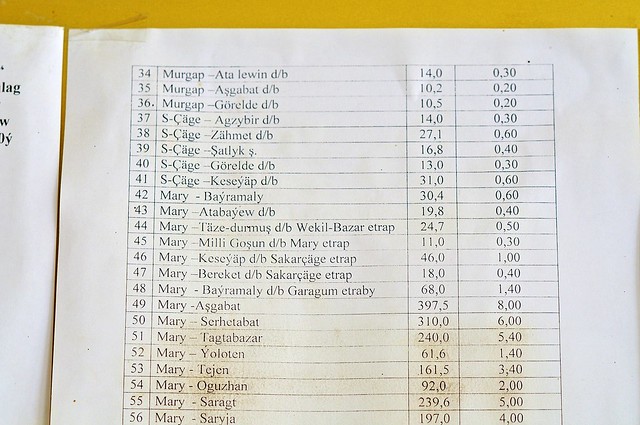

|

| Fare

sheet, showing the distance in kilometers followed by the fare in

manat. 400km to Ashgabat is 8 manat (same as the sleeper train), or

about $2.80. |

I hopped on the slow 11:45 bus and we dawdled our way east to Bayram Ali. As we got closer and closer, I was increasingly alert for any signs of old walls or any indication where I should get out. I eventually made the right call and got out just before the bus was about to make a turn into Bayram Ali, not far from the Abdullah Khan Kala (infuratingly, the LP map shows the edge of the Abdullah Khan Kala but doesn't show the adjacent roads which would illustrate just how close Bayram Ali is to the sites).

|

| Once again the

Bradt map trumps the LP version (though it still doesn't show canals

that may impede or prevent progress). The bus from Mary turns right at

the corner by the bazaar, on the road headed to Turkmenabat, and that's

where you should get off. Taxis back to Mary leave from about where the

arrow to Mary is. |

Merv

Merv owes its existence to the Murghab River (a different Murghab River than the one we say near Murghab, Tajikistan), which brings water from the Afghan mountains and unceremoniously dumps it into the arid Karakum desert near Merv. Because the Karakum is flat, the Murghab River spreads itself into a wide delta here, and this fertile delta is what is responsible not only for Merv but for the even older Bronze-Age site of

Gonur Tepe to the north (possibly the birthplace of Zoroastrianism, the first monotheistic religion), as well as the modern cities of Bayram Ali and Mary.

However, because of the flatness of the desert, it's easy for delta channels to dry up and new channels be formed. These wandering channels led to wandering cities, as settlements would follow the water over time, with the result that instead of cities being rebuilt on top of each other, we have a succession of ancient cities being built next to each other. There are two such cities in Gonur Tepe, and five different cities in Merv.

One of these cities is the

Abdulla Khan Kala, a Timurid city founded by one of Tamerlane's sons after the end of Mongol rule. Abdullah Khan Kala suffered from a lack of attention after the Timurid king decided on Samarkand as his capital. There's a moat surrounding the Abdullah Khan Kala, which is basically a huge square compound, of which nothing remains except the brick-faced rammed-earth walls: inside there is just a vast expanse of dirt and some hardy weeds, and maybe the odd goat or two. Even less remains of the the Bayram Ali Kala—the last of the five ancient cities of Merv and which was a western extension to the Abdullah Khan Kala—as apparently it was being used as a source of bricks when the Russians arrived in 1885.

|

| The western walls of Abdullah Khan Kala, from near the Bayram Ali bazaar. |

|

| Maybe "moat" is the wrong word. It's more like a ditch. |

Heading north from the Abdullah Khan Kala, you immediately enter a fairly rural area with lots of agricultural fields, and a few houses by the road. If you look at the Bradt map above, or the map in the LP, it looks like it should be a pretty straightforward walk between Abdullah Khan Kala and the Kyz Kala sites—much shorter than following the road and circling back to those sites, not to mention more picturesque as you can cut through green fields instead of walking the hot tarmac. But although the walk is more scenic, you can't actually get to the Kyz Kalas, as there is a canal that runs north-south just to the west of them. In order to cross the canal you've got to walk all the way to the ticket booth (or cross somewhere near or east of the Abdullah Khan Kala, which really isn't convenient), and while you would head there anyway, it does mean you have to backtrack to see the Kyz Kalas up close. Nevertheless, going through the fields remain a more picturesque way to the ticket center than the main road.

|

| Houses along the road to Merv sit cheek-to-jowl with ancient ruins. I believe this wall is likely one of the only remnants of the Bayram Ali Kala, other than the heavily-eroded rammed-earth walls opposite the Abdullah Kahan Kala. |

|

| The Greater and Lesser Kyz Kala ruins and the enormous and magnificent mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar, as seen from a farmer's field. |

|

| A similar view from 1911, captured by Russian photography pioneer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky. |

|

| The Greater and Lesser Kyz Kalas: fortresses that date to the 7th century. Located well outside the city walls at the time they were constructed (the nearby Sultan Kala city wasn't constructed until the 8th century), they were palatial rural residences. |

|

| The Kyz Kalas show a distinctly Mervian style of building known as khoshk, characterized by monumental earthen half-columns decorating the walls. |

|

| The Lesser Kyz Kala. This was as close as I could get, as there is an irrigation channel separating me from them. |

|

| The great Kyz Kala. "Kyz Kala" means "Girls Castle," and there are various folk tales explaining the name's origin, including one that has girls jumping off the roof when they saw the savagery with which the Mongols sacked the city in 1221, some six centuries after these buildings were constructed. |

|

| Just across the canal, the guard house for the Kyz Kalas. The signs for many monuments are in surprisingly good and informative English. |

|

| A great map of the ancient cities and their dates, from UCL. |

Following the inconvenient canal north, I was eventually deposited on the main access road to the archaeological zone, right next to the ticket booth. Apparently it was a slow day, and/or they don't get many visitors on foot who can quietly sneak up on the gate, as the attendant was having a snooze and I had to knock on the glass and wake her up. Right next to the ticket booth is a small museum which contains some artifacts (there are more at the regional museum in Mary), as well as some basic maps and models of the site.

|

| A pottery shard from the small museum next to the ticket office. |

|

| The museum's map. |

|

| A model of the area. Forgive the black triangles: they're the result of knitting together two pictures that really didn't line up very well. |

North of the ticket booth/museum is the mausoleum of Muhammed ibn Zaid, who was a Shiite leader who was killed in 740, and who is not actually buried here. Though not especially remarkable from the outside, it is still the location of considerable religious devotion (the most active religious buildings are frequently the least attractive), and the interior contains some ancient un-restored wall paintings and a well-loved tomb.

|

| A sacred tree covered with cloths that represent prayers. Again, seems pretty animist to me, which makes more sense when you consider that this is mainly a Sufist spiritual site, and not a mainline Shia site, despite it being devoted to a Shia scholar. I believe the building behind contained steps down to a well/cistern. |

|

| The wall is blackened where candles or torches burn. |

|

| A tomb covered with cloth. Obviously, you only ever see this on tombs that are still the object of considerable veneration. |

|

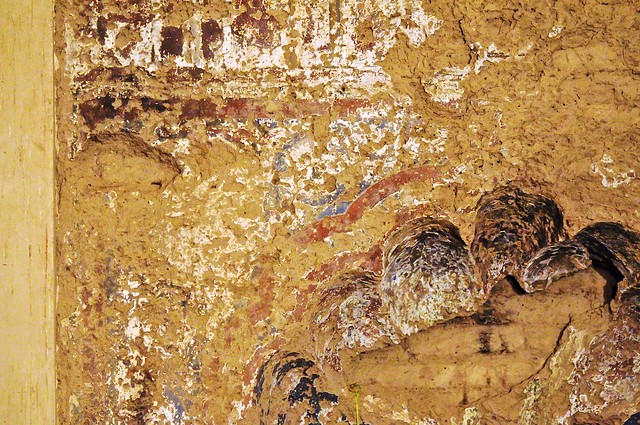

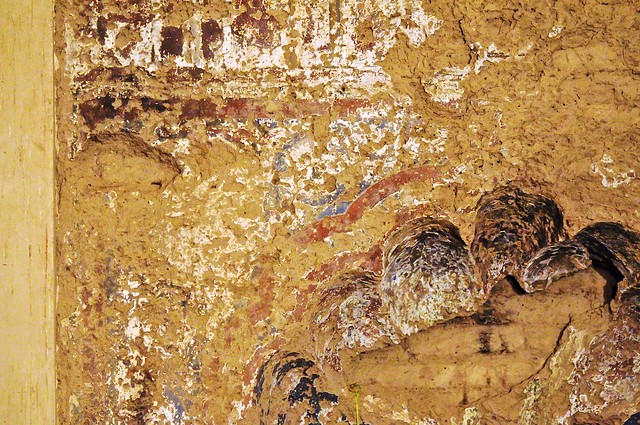

| The remains of old paintings. |

|

| Dome aperture. |

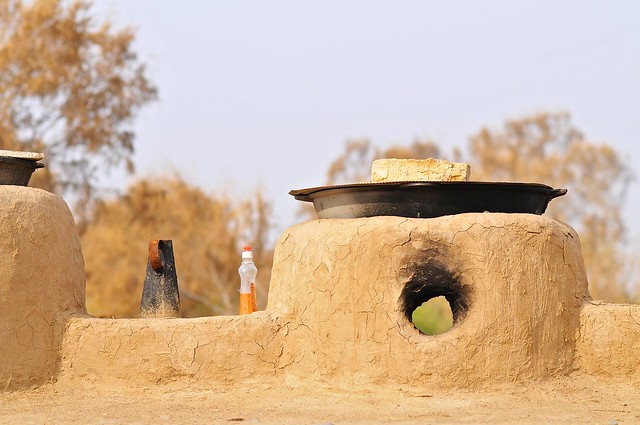

|

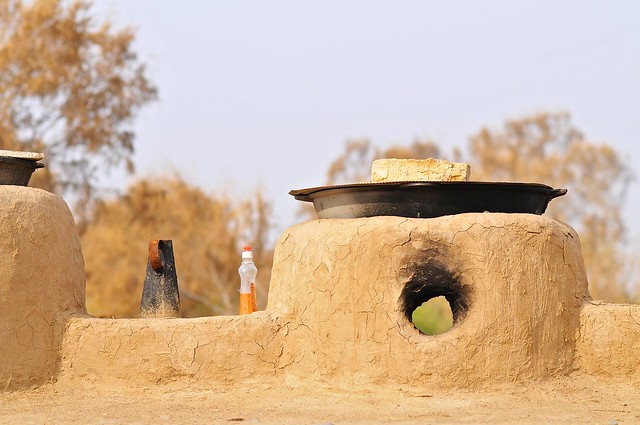

| A row of ovens near the mausoleum. |

|

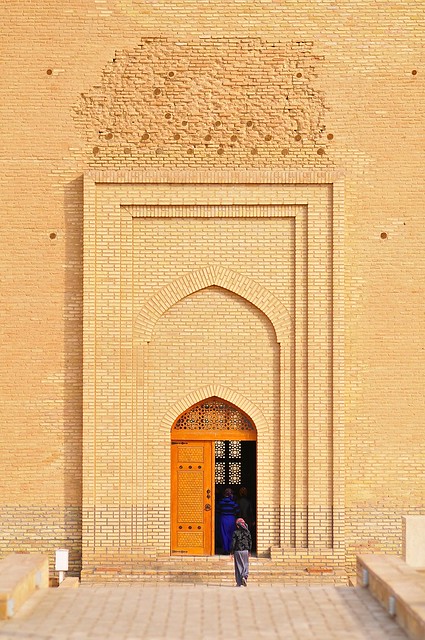

| The rear entrance to the mausoleum complex. |

|

| This unusual structure appeared to be inhabited by a resident scholar or imam, and served as a place of spiritual repose |

|

| From the ridge behind the mausoleum, a wind-swept tree overlooks the massive Sultan Sanjar mausoleum on the plains below. |

|

| Supposedly this mausoleum is visible across the desert from up to 30 miles away (or was, when the dome was still tiled). |

|

| Looking back over the mausoleum area, over a village along the main north-south road leading to Gonur. |

As I walked along the road to Sultan Sanjar mausoleum, I stopped at the Ahmed Zamchi mausoleum complex, just before crossing an irrigation canal and entering the Sultan Kala walls. These mausolea were interesting in an unremarkable sort of way—a good place to stop and take a drink and peek inside the buildings before continuing to Sultan Sanjar.

As I was leaving the mausoleum complex, as passing car roared up, stopped in the middle of the road, and a couple jumped out to take a picture with me. They then asked me if I was from California, and they must have been disappointed when I said no, because they promptly jumped back in their car and zoomed off. They didn't even offer to give me a ride! (Clearly I should have said that, yes, I was a a Californian.)

|

| The walls of Sultan Kala rise behind the canal. |

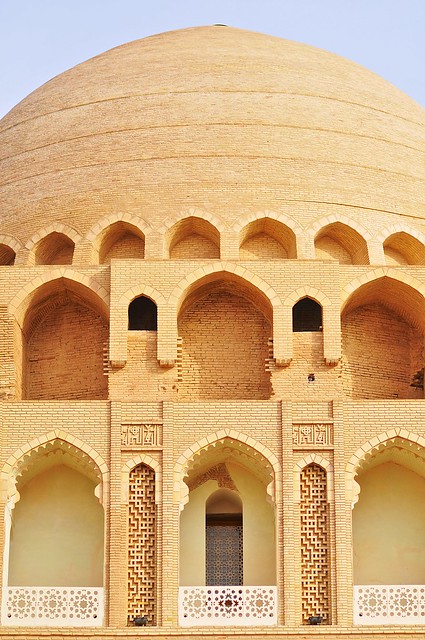

Mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar

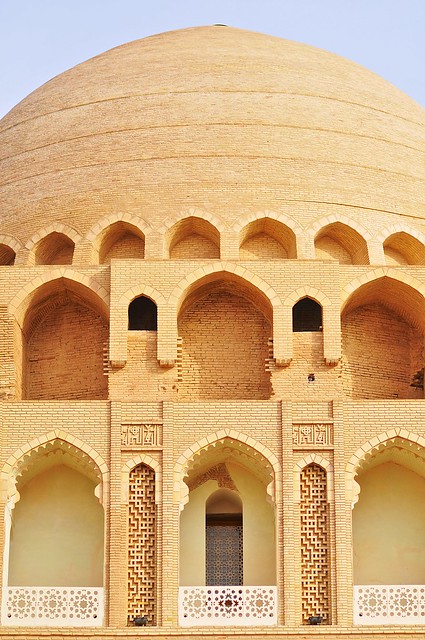

The mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar is, for my money, one of the most incredible buildings in Central Asia. For me, it really ticks all of the boxes: it has an incredible setting, far from modernity, and rising from empty desert; it's almost entirely monochrome (apparently the dome was originally turquouise, however); the design is simple yet highly proportional; and it isn't a crazy, circus-like attraction infested with touts and souvenir shops.

The mausoleum stands 36 meters high, with a base that is 27 meters square, and it was built before Sultan Sanjar's 1157 death. This places the building within the

Seljukid era, which began in the 11th century. Merv was the eastern capital of the Seljukid Empire during this time, and

Sanjar was its Sultan. So although we probably associate turquoise domes mainly with the later Timurid styles of architecture, it was the Seljuks who first used turquoise extensively. This ties in with the Bukhara's Kalon Minaret and it's band of turquoise tile, as this was constructed in 1127 by vassals of the Seljukids, the

Kharkhanids. Anyway, I probably prefer the way it looks now.

The Sultan Sanjar mausoleum is inside the walled city known as the

Sultan Kala, which was founded in the 8th century and at its height in the 11th century, which is when the walls surrounding the city were built. Somewhat ironically, it began to decline under the rule of Sultan Sanjar in the 12th century (which is when the Shahriyar Ark section of the Sultan Kala was built), before being sacked by the Mongols in 1221.

|

| The mausoleum from the elevated entrance area/parking lot/ticket-checker's booth. I made a conscious decision to not show the right side, as there was a bunch of scaffolding there. In retrospect, this was a dumb decision and I should have taken multiple pictures to stitch together later... you can always crop later. (On the other hand, very few pictures of the mausoleum show the southern side, where the scaffolding/structural support is) |

|

| The mausoleum in 1911. It actually looks more impressive and is more intact than I imagined. Take another look at the picture above and you can verify that all of the darker brick is indeed original. |

|

| Looking up at the dome. |

|

| Interesting wooden beams embedded only above the doorway. |

|

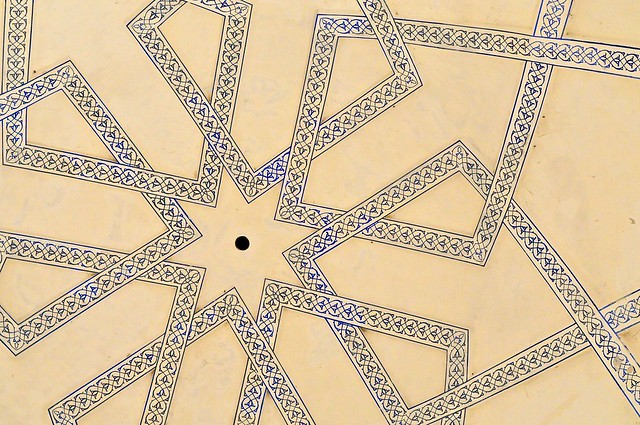

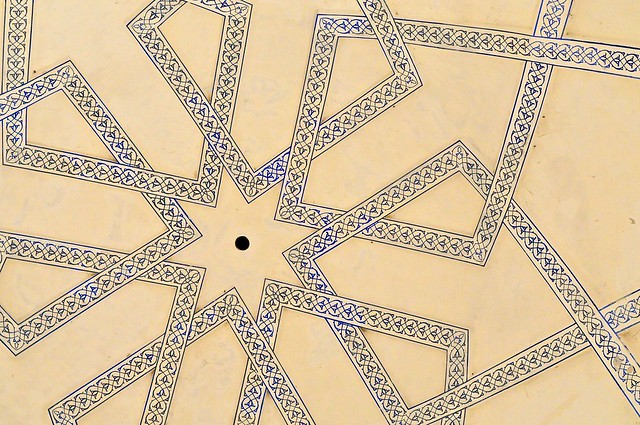

| Painted geometric patterns—almost all of which are reconstructions—line the dome. |

|

| Only small patches of original paint survive, but you can also see that the original decoration was much more extensive. |

|

| Delicately carved balustrades. |

|

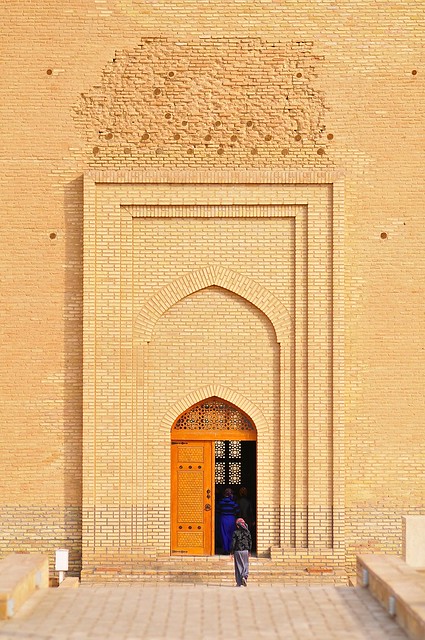

| Local women enter the mausoleum. |

The Shahriyar Ark

After the mausoleum I kept on walking, but the road is pretty boring so I headed off through the desert towards the Shahriyar Ark, which is a smaller walled area within the Sultan Kala. This area contains another

khoshk style building, this one called the Kepter Khana (pigeon house). It's in pretty good repair, and I don't think many people go there due to its distance from the main road.

|

| The Kepter Khana, as seen through a gap in the walls to the Shahriyar Ark. |

|

| Looking back at the Sultan Sanjar mausoleum from atop the Shahriyar Ark walls. |

|

| Dirt track leading to the Kepter Khana. |

|

| View through one of the apertures in the Kepter Khana. |

|

| Looking back at the Suntan Sanjar mausoleum and Shahriyar Ark walls, from atop the outer wall of the Sultan Kala. The Kyz Kalas can be seen in the distance, on the right. |

|

| The Kepter Khana through a hole in the Sultan Kala walls. |

Mausoleum of Khoja Yusuf Hamadan

Just outside the northeast walls of the Sultan Kala is the mausoleum of Khoja Yusuf Hamadani—a bustling (at least relatively speaking) religious complex of mostly modern buildings dedicated to the Sufist Khoja Yusuf, who lived in Merv in the 12th century under Sultan Sanjar. Apparently this was one of the few religious complexes allowed to remain open under Soviet rule, which helps explain why it remains such a popular place of worship today.

Although non-Muslims are not allowed in the mausoleum complex, I was able to climb the new minaret, which was most remarkable for the cloths that had been tied to the balustrade—something which must be unusual even by the typically shamanistic standards of Sufism, as this is an inanimate building, and a new one at that.

|

| As you come up the minaret stairs, the first thing you see are prayer cloths tied to the railing. |

|

| Cotton handkerchiefs seem to be the article of choice—no silk khatag as in Mongolia or Tibet. |

Gyaur Kala & Erk Kala

From the Khoja Yusuf mausoleum you head south towards the two oldest cities in merv: Gyaur Kala, and the smaller (and older), circular Erk Kala on its northern edge. The walk towards the Gyaur Kala walls is a bit strange, as there is a village nearby, and 20th-century houses are juxtaposed against ruined walls of ancient buildings located outside the walls, while dromedaries wander around grazing on the weeds.

|

| Camels and ruins just north of the Gyaur Kala. |

|

| Just hanging out near the road. |

|

| Sultan Sanjar mausoleum and the walls of the Shahriyar Ark in the background. |

|

| Are you looking at me? |

The paved road skirts the western walls of the Gyaur Kala and only enters the complex about halfway down—a detour that those on foot will not want to make. I set out across the scrubby plain to climb the walls on foot, but progress was surprisingly difficult because there were some thick bushes and marshy ground to cross before you got to the walls, which were surprisingly high and steep berms, like giant earthen dykes.

|

| From atop the Gyaur Kala walls, with the odd mix of ancient ruins and relatively modern houses, with the Khoja Yusuf mosque, mausoleum, and minaret in the background to the right. You can also see the salty marsh area (mainly dry, at the moment) and thick bush closer to the walls. |

|

| Although the Gyaur Kala walls (in the foreground) are impressive, the circular Erk Kala walls (in the background/center) are even more impressive, as they rise higher. |

Erk Kala is by far the oldest of the Merv sites, as it dates from the 6th century BC, and was created by the Persian

Achaemenids, in whose hands it remained until captured by Alexander the Great. After Alexander died, power shifted to the

Seleucid Empire (also Greek), which assumed control of Alexander's eastern conquests.

It's under the Seleucids that Gyaur Kala was constructed in the 3rd century BC, and it was quickly conquered by the

Parthians in 250 BC, who established Zoroastrian as the main religion. Almost 500 years later, in 226 AD, Merv was conquered by the

Sassanians, who remained in power until 649, when it was conquered by the Arabs, who made it the capital of the Khorasan region. After 750 it appears that Merv gradually declined in importance as other cities gained in importance, and it wasn't until the Seljukid made it their eastern capital in the 11th century (and constructed Sultan Kala) that it again approached its former importance.

|

| From the top of Erk Kala, looking over the interior of the Gyaur Kala. With the haze and the white salty ground, perhaps you can understand how I got the impression of snow at the border. |

|

| The walls of Erk Kala have been sectioned here, in order to help archaeologists understand the history of the wall. |

|

| Looking up at the Erk Kala walls and archer tower from the road that runs through Gyaur Kala. |

Aside from the massive walls, there's not much to see inside Gyaur Kala or Erk Kala. Although maps indicate a Juma (Friday) mosque in the middle of Gyaur Kala and a Buddhist stupa in the southeast corner, in reality there is nothing to actually see, except perhaps the faintest of mounds and an informational placard by the Buddhist stupa. If you have the time, they may be worth a visit, but for me it was a big waste of daylight (although the walk along the Gyaur Kala wall from the Buddhist stupa on the southeast corner over the the southwest corner was quite enjoyable). By the time I had left Gyaur Kala and was on my way to see the ice houses it was getting noticeably dark under the overcast, hazy skies, and I knew I had to hurry.

When I got close to the Seljuk ice house nearest Gyaur Kala, however, it became apparent that I would need to walk really far if I wanted to see it, as a canal separated it from the main road (the old LP map didn't show canals; the new one does, but doesn't really indicate where you can cross them, which isn't so helpful).

|

| The Seljukid ice house, on the other side of a canal. There's a road on this side, and a road on the other, but no crossing place. |

|

| There are a number of ice houses, all from different ages, but I wasn't able to visit any of them. Apparently ice would be cut and dragged into these buildings, and the domed shape would keep it cool into the summer months. |

|

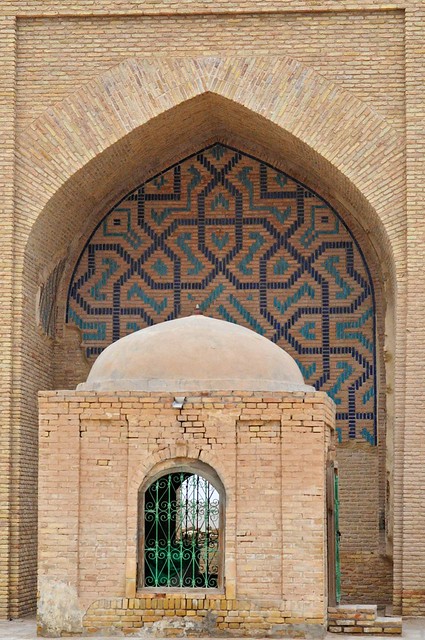

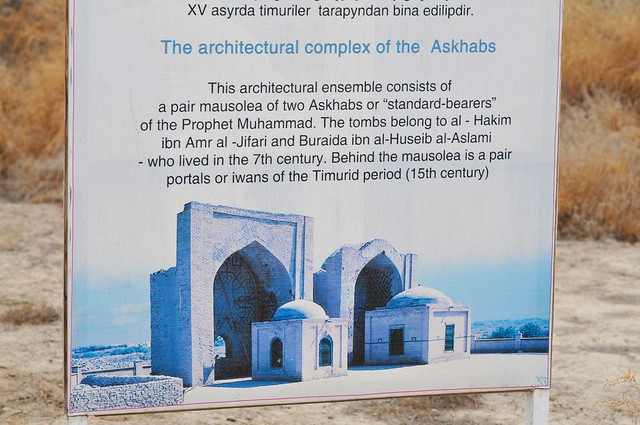

| The mausoleums of the Two Askhabs. Askhabs, or standard-bearers, are those who accompanied he prophet. It was getting well dark now, and I had to make a quick tramp across the scrubland from my ice house vantage point to get to these mausoleums. |

|

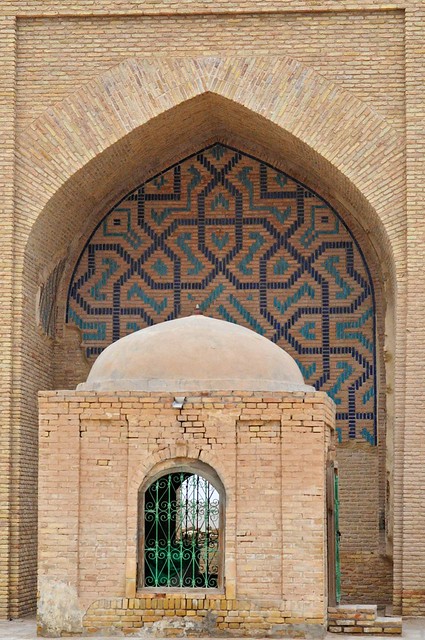

| The mausoleums are backed by 15th-century Timurid iwans which have been heavily reconstructed. If this was Uzbekistan everything would be covered with colourful tile, obscuring everything original. |

|

| Putting one of the iwans back together again. |

From the mausoleums I sped along the main road back to the Kyz Kalas, by which time it was well and truly twilight. I surprised the guard by appearing so late, but was able to walk up to the edge of the Greater Kyz Kala's interior and take a look. After a couple of minutes there, I headed south to the Lesser Kyz Kala, whose interior is freely accessible.

|

| The Greater Kyz Kala. On the right you can see the glare from the light near the guard house. |

|

| Looking north from the guard-house in the twilight. Those power lines on the left run along the damn canal. |

|

| The Sultan Sanjar mausoleum and Kyz Kala at dusk. |

|

| View from the Lesser Kyz Kala towards the Greater. |

|

| Another view, in the very last of the usable light. |

After packing things in when not even 30-second exposures would produce anything usable, I headed south along a dirt path back to Bayram Ali. It was a long time before I found a bridge over the canal, and after running into another one, I found myself at the eastern edge of the Abdullah Khan Kala. After walking through the empty old city and meeting fellow pedestrians for the first time all day—locals seem to use the old city mainly as a shortcut to the highway and market—I was back where I started.

It was pretty easy to find a ride back to Mary, as cars stopped on the side of the highway just out of town to pick up passengers. I was able to get a ride from a local just looking to make a bit of extra money as he headed back (at least that's what I assume was going on, as he didn't haggle hard or try to rip me off) for 3 manat, or about $1.10.

Back in Mary

It was fairly late when I got back to Mary that evening, and I had some interesting times with the guys in my room. One of them walked me down to a nearby eatery/bakery that was still open, and was a bit confused when I asked if they had potato samsas instead of the typical mutton ones—he needed convincing that I wasn't a vegetarian, and nobody in the region can quite believe that you might find a samsa that is 60% mutton fat to be somewhat unappealing—and I settled on bread when they didn't.

Back in the room, discussion turned somewhat naturally to the government and subsidies. They're the ones who first told me about the 1,400 liters of free gasoline that everyone gets every year, and they also said that all utilities are also free. And while this may buy a modicum of contentment, such measures don't really convince anyone that the government—or life under it—is good. And although Turkmenistan was a much more closed and inward-looking society than others in Central Asia, these guys were very much looking outside their borders. In fact, so much so that the conversation soon segued into them saying that they were happy I was sharing their room, and that when they went to Canada to look for work, they would all stay with me. Ulp. I kind of invited this by answering their questions about how much welders can make in Canada (though, like lots of embarrassed tourists, I low-balled the figure because I think it's very hard to imagine the different cost of living). They, however, were quite serious about this, asking my address and my phone number. I gave them my grandmother's, since I had no place of my own, but kind of had to refuse when they said they would call it to check. I'm not going to confuse my 93-year-old grandmother by calling her up from halfway around the world when she hasn't heard from me in 6 months. They finally relented when they called their mobile network and found out it would cost $6.00 per minute to call Canada. So this was another interesting experience, but again made me wonder about the exact nature of Turkmen hospitality.

Final Thoughts on Merv

Despite me not having enough time or daylight to see everything—no doubt because it was almost 12:30 by the time I got there and the sun sets early in mid-November—I believe that Merv is easily doable in a day, and I had no problem walking it. In the summer heat it might be another story, and I can understand why a car is recommended... even though I would personally still try to walk it, with plenty of water.

If you take the early train or an early bus or share taxi to Bayram Ali, you should have plenty of time to see the royal villa built for Tsar Nicholas, check out the bazaar, and to walk to pretty much everywhere in ancient Merv. If you decide to rent a car, I suspect you should be able to combine Merv with a trip to Gonur Tepe as well, especially if you do this in the summer and start early.

Budget

November 14, Mary: 31 manat

- Coffee and potato snack: 2 manat

- Bus to Merv and taxi back: 3.6 manat

- Bread: 2 manat

- Coke, chips, wafers: 6.2 manat

- Merv ticket: 17.2 manat

No comments:

Post a Comment