I returned to Almaty with a broken Kindle and without my iPhone. This meant I had no internet-capable device, and no handy way to get my email (assuming a wi-fi signal). I also was in need of additional storage space for my camera, as my 70 GB of storage were just about up, even though I was shooting in jpeg.

Incidentally, shooting in jpeg was a huge mistake (which I should have known, if only I had done some serious testing before leaving). I had always shot RAW before, but I had relied on bromides about jpegs from modern cameras being good enough for just about anything. For whatever reason, the jpegs produced by my D300 are atrocious. I mean, I'm not just talking about banding problems, but about severe and rather incomprehensible haloing as a result of its image processing engine. It's almost like the clumsy masking that you can see in some HDR photos. If you're wondering what I mean by this, look at the picture of Khan Shatyr, below.

Look at the edge of the illuminated tent, and notice how the area around the tent is artificially dark, and how it suddenly turns lighter a fixed distance from the tent, as though the tent has a dark halo. This is with minimal adjustment to brightness and contrast, and with more manipulation (to brighten the sky, for example) the effect will only become more evident. This horrific and inexcusable effect more typically appears in pictures where a darker object like a tree is pictures against a bright blue sky, where the sky immediately around the object is artificially light. Do any manipulation and the haloing becomes quite obvious. I only discovered this when I returned home and started to do some serious work on my pictures, by which time is was too late.

Anyway, since I was running out of space I already knew I would need either some new CF storage cards for my camera, or a portable hard drive to move files to. Given the difficulty in finding the less common CF cards, as well as the heightened expense that such a specialty product would have in smaller markets (SD and micro-SD cards were much more common, given their use in mobile phones as well as car stereos in the CIS), a portable hard drive seemed like the most likely option. But after I lost my phone, I gave serious consideration to a netbook. Thankfully I was in Kazakhstan when this happened, which meant there were real computer stores with reasonable prices: everything in Bishkek was at least 50% more than you would pay in the US (and if someone had decided to import things like Google Nexus or Kindle Fire tablets they could make a killing there). I found a refurbished ASUS netbook without an OS for 32,000 tenge, which was a reasonable price even by the low, low standards of US pricing, and decided to buy it. It wasn't that difficult decision, given that a portable hard drive would have cost at least 10,000 tenge, and likely more.

The decision to buy was only slightly complicated by a Canadian guy at the Apple Hostel who was interested in selling his Nexus 7 tablet, something which had only been released after I started traveling. He was happy with his Nexus phone, but I ultimately decided against it since it didn't have nearly enough storage and I would need to buy a hard drive as well.

This Canadian guy was really, shall we say, interesting. He was in his late 40s, and was Armenian-Canadian. He spoke Russian fluently, and was taking a year off to travel mainly in China, where—in his experience—foreigners are treated like kings. When I disagreed with that assesment, he said that maybe it was only white foreigners who were treated that way (although he was slightly swarthy, he strongly resembled Ron Jeremy, and said that his copious arm and body hair fascinated the Chinese). I think he's really the one who reminded me that I'm not white and that I do get treated differently than white Westerners, but some fair-haired Europeans at the hostel also disagreed about white people being treated like royalty, so I suspect that things have changed considerably since the last time the Canadian had been in China.

Anyway, he was spinning his wheels in Almaty because he had somehow managed to lose both his passports and all his travelers cheques (who carries these, anyway? ATMs give you just as good, or better, rates) on the streets of Almaty. Am-Ex was refusing to reimburse him because they found his account of his loss suspicious, and the Canadians were unable to issue a new passport in less than either 30 or 90 days (based on my attempt to get a new passport in Washington, DC, I believe it was the latter): the best they would do was issue him an emergency travel document to allow him to return to Canada. His Georgian passport (more on that in a minute) was his lone ray of hope, as they said they would be able to issue him a new passport in under two weeks, though he would have to go to Astana to pick it up.

How, you may wonder, does an Armenian-Canadian get Georgian citizenship. Well, according to him, the President Mikheil Saakashvili was a rabid xenophile with a Dutch wife, and he had instituted a policy where any foreigner (or maybe any Westerner) who lived in Georgia for more than 3 months could apply for citizenship. So that's what this Canadian guy did, and he got his citizenship. As a former CIS member with reasonably close ties to other former-Soviet republics, carrying a Georgian passport made travel within CIS states considerably easier. It sounds preposterous, as did his claim that Saakashvili mandated that foreigners be given a free bottle of wine on arrival at the airport, but that was his story.

As a result of losing both passports and all the money he had on him, he had to make a lot of phone calls to different parts of the globe. This involves different time zones. Because this was very confusing, he decided on the basis of his confusion that everyone in the world should switch to a common time system. And since we would all be switching, anyway, why stop at the simple adoption to GMT or UTC? Why not go to a complete base-10 system, and away from 60 minutes and 24 hours? I pointed out that

Swatch Internet Time, with its 1,000 beats per day, embodies exactly this idea, but for some reason had not been widely adopted. He was very insistent that the idea was superior and that change should be foisted upon us, and could not be convinced otherwise.

For someone who looked like Ron Jeremy, he had a surprisingly intense interest in younger women. Although he had been in Almaty for less than a week, he had already gone on a date with a divorced Kazakh woman he had met through an online service. As a divorced woman with a daughter, I suspect her prospects in Kazakhstan were limited, and perhaps someone with a Canadian passport sound appealing. That's the only thing I could figure. He was also very enamored of this Georgian girl who had once interviewed him about how he obtained Georgian citizenship, saying she dressed like a hooker in her Facebook pictures, and was eager to show them to a Dutch guy who was going to Georgia. She was in her mid-twenties, and the Canadian said she was almost too young for him. The Dutch guy then asked him who he would consider to be too young for him, a question to which we never got a real answer.

Despite his quirks, he could be an interesting guy to talk to, as he speaks Russian fluently and Russian is what everyone in Kazakhstan speaks. Unlike in Kyrgyzstan, where Uzbeks will speak Uzbek to other Uzbeks, and Kyrgyz will speak Kyrgyz to other Kyrgyz (although the language are both Turkic, as are Kazakh, Uyghur, and Turkmen, there are enough differences to make them only as mutually intelligible as Italian and Portuguese, for example), Kazakhs will speak Russian even when amongst other Kazakhs. To a large extent this is because many Kazakhs speak no Kazakh, and even more are not fluent in it. Indeed, it is remarkable to hear Kazakhs actually speaking Kazakh in public.

The Canadian's view on this was kind of surprising, because he thought Kazakhs should use their local language more. The reason this was surprising was because he also thought that there should be no sympathy for people like the Georgians who insisted on using a backwater language with a unique writing system that effectively limited their economic opportunities as compared to if they all spoke Russian or another major language. In his mind, economic progress was really the only thing that mattered, which is why he was also effectively on the side of the Han in dismissing the complaints of the Uyghur and Tibetans in China. On the other hand, he was also critical of Japan, which hasn't apologized for war-time and colonial atrocities in Nanjing and elsewhere, and where the Prime Ministers continue to visit

Yasukuni shrine, where multiple convicted war criminals are interred. I pointed out that this kind of anti-Japanese antagonism only makes sense from a moral perspective, and not from an economic one, and that if we were adopting a moral perspective then the Han treatment of Tibetans and Uyghur were equally problematic.

He eventually got really mad at me and told me to stop talking to him when I pushed back against his time-zone idea and suggested that it would introduce a lot more problems than it solved. I think everyone else in the hostel (and life) was content to simply tolerate his views as the source of amusement, especially since he had some difficulty understand when people were taking the piss out of him. At one point he touched the screen of someone's laptop, then apologized for doing so. I said that he probably didn't like it when people touched his screen, and he said that when people at work did that to his computer, he would briefly excuse himself and walk to the bathroom, return with a mess of wet paper towels, scrub and dry his screen, then turn back to screen-toucher and ask them to continue their thoughts. He said this usually prevented them from doing it again. I suspect it prevented them from ever visiting him again.

But it was nice to go out with him and have him be able to translate things or decipher menus or ask what things in cafes were.

|

| The Green Market in Almaty is a nice mix of an organized Central Asian market and Western hygiene, especially in the central fresh-market area. The surrounding areas are just seedy enough to feel exotic and "authentic." |

Almaty is a very chic place. There are top-notch international stores and brands, and in many ways it feels like what I imagine certain Baltic states must feel like: very European and modern, but with unmistakeable traces of Soviet influence, or that it had been a little down on its luck not so long ago. The edges are roughest around the Green Market, but they never really get that rough.

Part of that is because of the people, who are really very young and stylish. The German girl I met in Xiahe said the women were really attractive (something I also heard from others), and it's true: they are. I'm not sure many of them are actually any different than Mongolians or Kyrgyz so far as fundamental appearance goes, but it's just that they dress like Russians, put as much money and effort into their appearance as Russians, and have very Western style sensibilities combined with the resources to implement those sensibilities. What does make some Kazakh women unique, however, is that the large numbers of Russians in the country have resulted in some Kazakh women being of mixed heritage, and many of these women (and men) can be incredibly stunning (and perhaps the only people from whom the word "Eurasian" actually makes any sense). Sometimes Russian blood manifests itself in light, sandy hair, which is sometimes explained as them being "real" Kazakhs, on the theory that many in Chinggis Khan's army had fair hair. Other times it's visible in a mixture of Asian and European facial features, or green eyes. Sometimes the effect can seem a little awkward, in a captivating sort of way, while sometimes it is simply stunning. People of mixed ethnicity are relatively rare, however, and it is even more rare to see someone who appears to be the direct result of inter-ethnic parents.

|

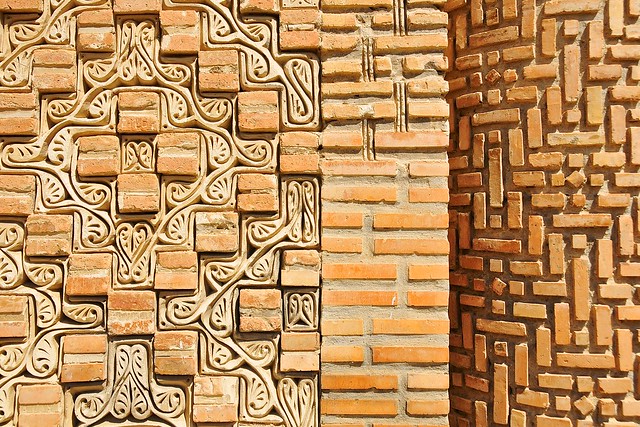

| Interior of the mosque. |