The Gates of Hell

Because of my late night of internetting, I got a pretty late start on the 31st. I went to the supermarket to spend the last of my som, got some fried snacks from my favourite vendor next to the mosque, then hopped a marshrutka to the Uzbek border (which is just on the northwestern edge of Osh). It was a little after 1:00 when I arrived, and although there were lines at the Kyrgyz exit post, it only took a few minutes to pass through.

But after I passed into no-man's-land between the two border posts that I realized the insanity into which I had passed. This wasn't the big multi-kilometer gap that often exist between border points (and which frequently function as opportunities for mandatory but extortionate taxi shuttles): as an urban border point, the border-control outposts were close to each other. But because Uzbek border officers are ridiculously slow and engage in detailed searches and questions, people are stamped out of Kyrgyzstan much faster than they're stamped into Uzbekistan. So it was that there were hundreds and hundreds of people crammed into a space the size of a high-school gymanasium, which was completely uncovered and exposed to the mid-day sun. In the height of summer it must be excruciating, and extremely dangerous. The Uzbek exit from this no-man's-land compound was a gate, with a sturdy chute leading up the gate: think of a cattle pen and you won't be far wrong.

When I initially arrived, there were these touts perched on the railings of the chute that led to the actual gate to the Uzbek customs/passport area, frantically shouting with the people trying to cross into Uzbekistan. I had no idea what that was all about, but it wasn't official in any sense of the word, and certainly didn't reduce the crush of people trying to push their way to the front of the line. Also, women and men were segregated, with men on the right and women on the left.

Anyway, shortly after I arrived in this pen, a Kyrgyz border guard showed up and started pushing everyone around, and dragging people out of line and then pushing them to the back of the "line." This wasn't gentle pushing, but hard shoves that made a few people fall down, including some women. One elderly woman objected to this, and got slapped in the face after she pushed back. But after pushing people around for a while, and forming a quasi-line, he would leave for a few minutes and a knot of people would reappear near the chute... with the net effect that those who stayed in the line ended up further and further back, while those who pushed forward were able to consolidate their forward position when the soldier came out and re-formed the line.

Anyway, after going through this for about three hours—during which time one smartly-dressed family was given VIP treatment and escorted through the border by a guard—I was further from the gate than when I started. So when the policeman left for an extended period, I joined the throng of people pushing their way to the very front, and the touts re-appeared. It seems that these touts (who didn't seem to actually be taking any money, so perhaps "tout" is the wrong word) act as unofficial gatekeepers, and assign people numbers. This kind of makes sense, but works very poorly in practice since everyone pushes to the front despite having a number. Now, since I had no number, the touts were saying I could not exit, even though I had been there for over 4 hours. So this is one of the few occasions I decided to take advantage of the tourist's privilege of being something of a jerk, and I started to get really loud and shout at this guy who was trying to pull me away. This is really out of character for me, since I tend to speak quietly. Actually, I was just acting like them, as I had the group of 3-4 touts shouting at me, and I figure it's fine to shout back. This resulted in one of the touts, whose face I was in, getting rather startled and grabbing me by the neck as though the was going to choke me. This didn't go down very well with the crowd, who could clearly tell I was a foreigner by the way I was shouting in English, and they made the guy get away and let me join the next group to enter the chute. While in the chute an elderly lady behind me lost consciousness as we were being crushed against the fence by all the pushing from behind, with the heat no doubt making things more difficult. They had to pour a couple of bottles of water over her before she regained consciousness. I'm surprised no one dies at border crossings like this (heck, maybe they do), and it was somewhat ironic that there was a big billboard on one of the walls indicating that the OSCE had provided assistance to this border point.

Once inside the Uzbek border office, everything is serene and things move very slowly despite there being multiple border officers and only a few people admitted at a time. You have to fill out a detailed form asking for how much money you have (if you exit with more money than you bring in, you will have a problem), any valuables you have with you, and other questions. Then you have your bags inspected and X-rayed. I figure they process about 25 people per hour at that speed.

Megi passed through this border a few days later and indicated that foreigners/tourists are usually let through immediately and not made to wait with the locals, but that wasn't my experience. And even though I can possible pass for a local in appearance (but not in dress), I'm pretty sure the border guard knew I was a tourist since he seemed reluctant to push me nearly as hard as he was pushing the locals, and I told him in English that I had nowhere to move. At any rate it was an interesting insight into local life, and the trials and tribulations they endure. Needless to say, however, it wasn't a great introduction to Uzbekistan.

I didn't have much time in Uzbekistan—my visa expired on November 15th,

since the embassy in Dushanbe decided to ignore the dates on my

application and LoI and start the clock on the date of issue—but I

decided that since I was in the Ferghana Valley I should see something

there. Given that Margilan has a large bazaar that is only open on

Thursdays and Sundays, and that it also has a silk workshop, I decided

to spend my first full day—a Thursday—in Margilan.

On Uzbek taxis and black-market exchange rates

A short distance from the border is a big parking lot where people gather to meet those crossing over, as well as taxis for shared transportation to other cities. Most of these taxis were for Andijon or other larger cities, and it was difficult to find people going to Margilan. I was a little worried since it was after 5:00 and getting dark by that point, but I found a car heading to Margilan and we began to bargain over the price. Now, taxi drivers everywhere try to rip people off, but in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan the initial quote tends not to be outrageous: at most you'll be quoted twice the normal price, and usually the asking price is maybe 50% more expensive than you should pay. So that was my baseline for comparison, and although Lonely Planet indicates how much transportation should cost, their prices seem absurdly low in comparison to the distance covered (it's 120km to Margilan) and the price you would pay in Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan (subsidized fuel prices are responsible for this). I was originally quoted six times the proper price, and ended up paying double the price that locals in my car paid when they arrived in Margilan.

Of course, to pay for my taxi ride, I first needed to obtain some Uzbek som. Getting som in an efficient way is more difficult than you might imagine, for a couple of reasons: Uzbekistan has a black-market currency exchange rate that gives you about a 30% better rate than the official rate, meaning it is always better for travelers to exchange their dollars on the black market; and there are almost no ATMs (it seems like there are less than 20 in the entire country, while in Kyrgyzstan and Dushanbe it was very easy to get dollars from ATMs) that accept international cards and dispense dollars.

When I explained to the driver that I needed to get some som, as I only had dollars, he made a quick phone call and arranged for us to meet a money changer in a town near the border. We pulled up to a random place and out came a woman to change money. As I wasn't sure if I would be getting a good rate (it's difficult to get up-to-date information on the current black-market exchange rate), I only changed $100. Of course, since the exchange rate was approximately 2,800 som to the dollar, and the biggest note is 1,000 som, I ended up getting a big bundle of money. I started to count it (Burma has similarly ridiculous currency, and I learned that sometimes the changers try trick you by using different denominations, especially when changing a lot of money), but after doing a spot check I figured everything was in order. The rate I received was 2,670 som per dollar, which was actually a decent rate.

I wasn't able to see much in the darkness, but my initial impression of Uzbekistan was that it was much more highly populated and developed than Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which is perhaps unsurprising since I was in the Ferghana valley, which is flat and fertile in a way that most of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are not.

Margilan

When we arrived in Margilan, I was dropped off near the cheap hotel mentioned in LP, but when I rang the bell at the locked lobby, the operator told me that they were no longer allowed to accept foreigners and that the only place in town was the Hotel Atlas, and he asked a couple of nearby kids to show me the way there. I already had a good idea of where it was, but I let the kids lead me to the main street on which the hotel was located. On the brief walk we were joined by some of their friends, and they asked me to take their picture. After this, however, they asked me for money (for their guide services or their picture, I'm not sure), which I declined.

|

| My guides, shortly before I refused to give them any money. |

I started walking down the main road leading to the Atlas, stopping at a supermarket (which felt more like a specialty shop, with waist-high shelves, lots of things behind counters, and lots of staff hanging around) and checking out some of the stores I saw. Things in Uzbekistan felt surprisingly different.

|

| Apparently leeches are used in Uzbek medicine. Note the weird mixture of Latin and Cyrillic scripts in this sign. Uzbekistan officially switched from Cyrillic to Latin for Uzbek, but Russian is written in Cyrillic, so I'm not sure what the change really accomplishes except adding another script. |

|

| These kind of smart-looking boutiques aren't much seen in in Kyrgyzstan or outside of some parts of Dushanbe, and are part of what immediately makes Uzbekistan feel more prosperous. |

The Lonely Planet suggested that the Atlas should have reasonable rates, but one look at the building and it seemed highly unlikely. It was an impressive building with an elegant lobby, and when I inquired they said their cheapest room was $55. I'm not much one for negotiating hotel rates, but I was in a jam but they wouldn't budge. There's no way I'm going to spend $55 on a hotel room, though, so I left to try and find some place to spend the night. I ended up finding a traditional chaikhana that was open 24 hours, and I spent the night there drinking tea. I don't think it would be possible to do this anymore (in Uzbekistan you have to stay at registered hotels at least every few days, and they've started to require that you stay in a registered hotel every day when you're in the more-religious Ferghana Valley), but it was an experience.

That's not to say it was a pleasant experience, however, as it was full of weird little moments that you simply wouldn't see in Kyrgyzstan on Tajikistan. I fired up my netbook to watch a movie, and I was interrupted by a guy who just walked up to me, sat down next to me (sitting partially on my camera bag), removed one of my earbuds and stuck it in his ear, then started pressing buttons on my computer in order to try and play the movie (I had paused it). There were no salaams or the customary questions, he just launched into this. His first attempt to communicate with me was to gesture that he wanted to buy my netbook. A very weird encounter. A little later a man walked up to me and said a prayer, then asked for money. Definitely not the greatest welcome to the country.

I left as it started to get light out the next morning, exploring the town. It was pretty dead, and even the mosque was empty (a bit surprising given the traditional dawn call to prayer).

|

| Almost all cars in Uzbekistan are Daewoo or, if newer, Chevrolet. This is the result of domestic car factories formerly owned by Daewoo but now controlled by Chevrolet, plus onerous duties on cars imported to Uzbekistan. The little Chevy Spark is very popular. |

|

| Inventive fast food joint. The inverted arches resembles the Cyrillic character for "sh," suggesting they sell shaurma/shawarma. |

|

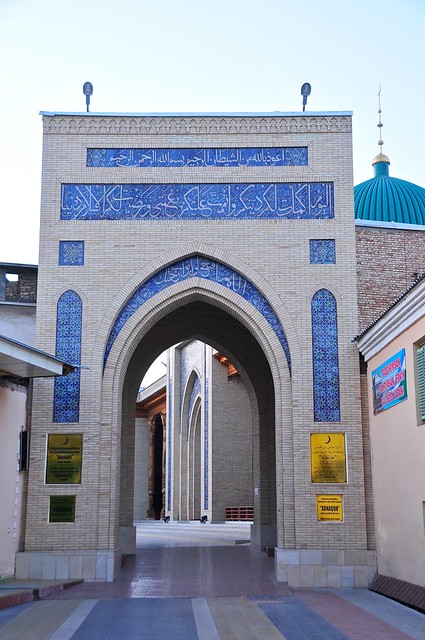

| The entrance to a mosque and madressa in central Margilan. |

|

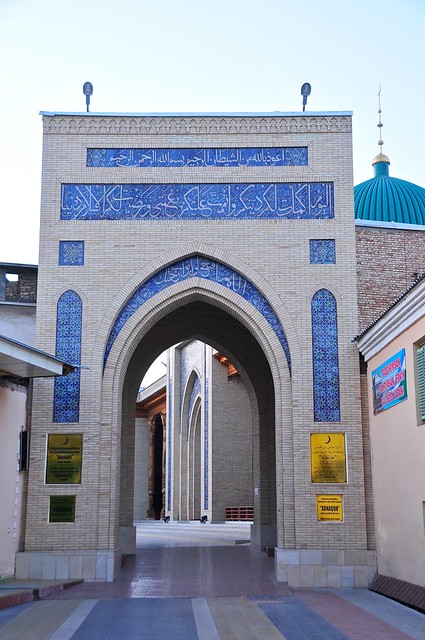

| The new building is flanked by old wooden parapets on the madressa. |

|

| View from madressa stairs. |

|

|

| View from the top. |

Yodgorlik Silk Factory

As it began to get later and the town came alive, I tried

to find one of the main attractions in Margilan: the Yodgorlik Silk

Factory. Good luck trying to find this place on your own if you only have the Lonely Planet to go by, as many locals either don't know where it is or can't give directions decent enough to find it. I added it to Google Maps so it should be there now (but if it's inaccurate, you also know who to blame), but I had a heck of a time trying to find it when I was there, even after asking locals.

Much of what you see at the Yodgorlik is the same as at the

Atlas workshop in Hotan, except that here you get a guide who speaks English, and a bit better explanation. The people at Yodgorlik also seem to be actually practicing the traditional silk-making techniques, whereas at Atlas it seemed largely for show.

As my guide was starting the tour, one of the workers approached him to talk. Now, the worker was female and my guide was male, and since Lonely Planet describes Uzbekistan's Ferhana Valley like it is the most conservative place in all of Central Asia I expected the conversation to be distant and formal. That said, I was surprised when they started by shaking hands and then talking in a very friendly way—you simply wouldn't see unrelated Uzbek men and women shaking hands in Osh, let alone in somewhere even more conservative like the Fann Mountains.

|

| The cocoons are softened in hot water, then strands from a bunch of them are gathered together |

|

| They're then threaded through a grommet. |

|

| Then spread out again under the upside-down bowl, then bought together again at the top of the canvas, then fed to the spinning wheel. |

|

| Cocoons and the silk worm inside. |

|

| Tying bundles of silk in preparation for dying. The tied sections resist the dye, and you have to re-tie the bundles with each successive colour. |

|

| Some of the spices and plants used to naturally dye the silk. |

|

| The same sort of looms that we saw in Hotan. |

|

| Except there are more people weaving here, and the room is appropriately scruffy and cramped as befits a real, working factory. |

|

| They also have (very noisy) automated looms at Yodgorlik. |

|

| In their shop they sell not only silk products but carpets and ceramics. |

|

| These kinds of ceramics are very common at all tourist sites in Uzbekistan, and are actually quite attractive. In nearby Rishtan there's a famous workshop. |

Kumtepa Bazaar

Kumptepa is a huge semi-weekly bazaar on the outskirts of Margilan, operating on Thursdays and Sundays. For some reason Lonely Planet seems quite enamored of this bazaar, but we obviously have very different tastes given that they also like Osh's bazaar a lot, too. But although Kumtepa is big, is pretty darn soulless, with an industrial feel and little charm. Sure, there are large sections selling silks and fabrics, but you see this at a lot of bazaars, and much of the bazaar deals with hardware, parts, and other random things.

It is pretty easy to get there, though, as regular marshrutkas run there from the east-west road running past the central green market, which is just north of the Yodgorlik workshop.

|

| Sewing machines, bric-a-brac, home appliances, and all sorts of stuff are sold at Kumptepa. |

|

| Woman sell nuts and fabrics, but most of the sellers are men. |

The green market

Back in town, the green market was actually a lot more interesting to me. As in Dushanbe and Almaty, they artfully stack their produce in little pyramids, which is so much more appealing than random piles of fruits and vegetables.

|

| There are often sections devoted to pickled vegetables, including a surprising number of Korean salads. |

|

| Women sell the salads, while men sell the produce. This style of covered market is typical of Uzbekistan. |

Margilan to Tashkent

With the help of a local I was pointed in the direction of the gathering point for share taxis to Tashkent, and once there I stuck to my guns and negotiated down to the price listed in Lonely Planet. This actually involved the driver pretending he wouldn't agree and me standing around for a while until another driver agreed (not much risk with this strategy, as you're going to be waiting for the car to fill up, anyway). The upshot was that I paid 27,000 for the 315km ride from Margilan to Tahskent—the exact same as I paid for the 120km ride from the border to Margilan.

|

| Hay stacked by the side of the road. |

|

| A motorbike and cargo-carrying side car. |

The Ferghana Valley is separated from the rest of Azbekistan by a small

chokehold of the Tian Shan mountains, pinched from the north by

Kyrgyzstan and the south by Tajikistan. The Kamchick Pass rises to 2,267

meters, while the Ferghana Valley is between 400 and 450m, while

western Uzbekistan is even lower. There's a police checkpoint in the

pass, where documents are checked (Uzbekistan seems fearful of Islamic

funadmentalism, and the Ferghana Valley is the most devout region of

Uzbekistan).

|

| Billboards on the mountain ridges hint at Uzbekistan's economic development. |

|

| These weird frames that look like they might be for placement of solar panels—or for preventing avalanches in the winter, line some of the slopes. |

It was dark by the time we arrived in Tashkent, which has a population of over two million. On the outskirts of Tashkent there was another weird inspection station, but I think this one had more to do with tolls or car inspection than anything else, as we got out of the car while it drove to some inspection station, then rejoined it when it reappeared about 100 meters down the road. This happened to pretty much all the cars on this road, so there was a bustling business in selling snacks and refreshments. It was all a bit bizarre, and although we were still quite a ways from he city, signs of urbanization were evident soon thereafter, as Tashkent is a sprawling city.

We were dropped off somewhat near the train station, and I followed a tram line back to the station, and after checking out the train schedules I took the subway to Chorsu, where I tracked down the Gulnara Guesthouse in the old town (the main street on the border of old town is full of upscale bars and KTV joints, so stepping off them into the old-town alleys is interesting).

Tashkent is pretty expensive, and at the Gulnara it was 42,000 som—$15—for a bed in the dorm room, breakfast included. That being said, the guesthouse was actually pretty nice, with real furniture like a real house, and not the spartan decoration and cheap furniture that you tend to see in guesthouses, hostels, and cheap hotels. What's more, it had an actual bath in one of the bathrooms, so I was able to indulge in a short bath for the first time since Jeti-Oguz. As a bonus the Gulnara issues registration slips for stays of even one night (you need to stay in a registered hotel at least once every three nights, where they give you registration slips that you may have to show to the police or border officials, but some hotels won't register you or give you slips unless you stay a certain number of nights).

Budget

October 31, from Osh to Margilan: 270 Kyrgyz som + 31,300 Uzbek som

- Fried goods: 30 som

- Chocolate, snickers, bread, cookies, tissues, coke, etc: 240 som

- Taxi from Dostyk to Margilan: 27,000 som

- Internet: 2,500 som

- Drinks: 1,800 som

November 1, from Margilan to Tashkent: 81,700 som

- Grechka, tea & sugar at overnight chaikhana: 6,400 som

- Taxi to Kumptepa: 1,800 som

- Taxi to Tashkent: 27,000 som

- Room at Gulnara: 42,000 som

- Bread, 2 drinks, carrots: 3,200 som

- Internet: 1,600 som

- Subway: 700 som