Border woes and border bliss

Although I was supposed to be picked up early in the morning, the driver rang the hotel to let them know we wouldn't be leaving until closer to noon. As the day dragged on, the time was pushed back, and we didn't actually end up leaving until the middle of the afternoon. This was a disappointment (but about par for the course when trying to travel cheaply in Central Asia), as it meant that it would be dark by the time we arrived at the Tajik border. I figured that I would probably try to get out at Karakol and spend the night there, and then continue on to Murghab the next day, so as to be able to enjoy some of the high Pamir scenery.

And so it was that we arrived in Sary Tash at dusk, where we filled up on cheap Kyrgyz gas before leaving town and heading south towards the Kyzyl-Art border. Although the Trans Alay mountains on the southern side of the Alay valley look close, they are actually some 40km from the northern side of the valley—and the road to the border, unlike the east-west highway that runs through the Alay Valley, is rough and crumbling.

The Kyrgyz border station, Bar Dobo, is in the valley floor, at the start of a sub-valley that cuts its way up the Trans Alays. Getting stamped out of Kyrgyzstan was simplicity itself, as the driver simply grabbed out passports and ran into a nearby building where the border guards were located. By this time it was dark and cold at this altitude, so we were all happy to stay inside the right-hand-drive Pajero.

After being stamped out we started driving up towards the border, switchbacking up the mountain towards the end, before summitting at the the 4,280 meter high Kyzyl-Art border.

A Tajik border guard approached and took our passports from our driver. This is when the problems began: although I had a visa and the required GBAO permit, they were claiming that this border could only be used by tourists leaving Tajikistan, and couldn't be used to enter Tajikistan. Although this should have been true during the period when GBAO was off-limits to tourists, it made no sense now that the territory had reopened for tourists.

Of course, something could be arranged, but only if I paid them $100. This was pretty outrageous, and a price I wasn't willing to pay. My driver really wanted me to pay, as he would have to drive me back if I was rejected, and when I said that I only had $20 on me (this was really the only small currency I had on me), the border guards rejected this amount, and I was denied entry.

The driver thus had to bring me back down the mountain. There was a small building about halfway between the border posts, and although there was supposed to be someone there who would let people stay there, the building was uninhabited and locked up tight when we arrived. We had to go all the way back down to the Kyrgyz border post, and after a brief discussion they let me stay with the customs guards in one of the buildings.

I was kind of surprised by the border post buildings. Although they were in the middle of nowhere, they were much nicer than most houses you see in places like Sary Tash or Sary Moghul, no doubt because they were Soviet-built government buildings. Instead of having stoves for heating, all the buildings had hot-water radiators and were really quite warm. The rooms I was allowed to see were empty, with typical tapchan-style mattresses and bedding being laid out at night. Despite being Soviet built, and originally having a decent shower block

in the basement (the showers apparently no longer functioning, however),

the toilets remained long-drop outhouses.

One of the younger off-duty guards spoke pretty good English and wanted to know if he could play a video on my netbook. It turns out he wanted to watch a video that had been taken by a visiting TV station that was covering border security patrols (Tajikistan being a smuggling point for Afghan drugs, and this border being one of the borders through which drugs transit). But really he wanted to have a bit of a laugh about his boss, who was narrating one of their night patrols, but who was also so out of shape he had to stop and pant every minute or so as they walked outside.

Racism: one of the top American cultural exports

The next morning, we were joined at breakfast by an older officer who was quite the character. He spoke basically no English, but was an effective mime, and made fun of his partner when he heard him approaching, mimicking a trudging giant. He then said he had a wide nose, and looked African. Uh oh... do we have a Soviet-Kyrgyz racist here? I still don't know what to think, but he was just getting started and it was about to get much more complex. It turns out that—according to him—his partner actually did have some African ancestry, though it's difficult to see.

What's easier to see is that there is a generational and geographic difference in how people view race, and that American media doesn't always translate well or communicate positively; although this older Kyrgyz guy didn't know English, he did know the N-word. I don't think he knew how it is understood in Western—let alone North American—culture, but his younger colleague did and was clearly uncomfortable translating what he was saying. But basically, he started out by saying his partner was "half-nigger" (I'm going to use the language he used, because I think it's the only way to properly communicate the impact of what he said on my ears, and convey the complexity of the situation). Which was shocking for me to hear, and uncomfortable for his translating colleague to hear, but I honestly think he was oblivious to the baggage associated with the word. I say this because he then told me about how much he loved "niggers," saying he loved their lips and asses. He then went on to talk about the type of people he loved, including Halle Berry, Jennifer Lopez, and (somewhat surprisingly) Katherine Zeta Jones, asking me if I had any pictures of them on my computer. He then showed me pictures of himself he had taken with a couple of black American girls at the border, commenting on how beautiful they are.

It was an interesting experience, and as I said I'm still not sure what to make of it. There's certainly something to be said about the corrosive effect of American media in popularizing and even legitimating certain racist phrases and stereotypes, and while there's also some sort of sterotyping going on with the border guard (who also likely harbours anti-Uzbek sentiment, for example), I'm not sure if I should think of his stereotyping as qualitatively worse than North American stereotypes about Russian women, or "Asian" women, or anything along those lines. I mean, this is a guy whose only exposure to black people comes from movies/media and the very odd tourist: to the extent he harbors views about blacks that we would consider racist, to what extent is he or Kyrgyz society to blame, and to what extent is the West?

Anyway, after our interesting breakfast we went outside where they were inspecting a couple of old Soviet-era trucks coming back to Kyrgyzstan. They were largely empty, as I think they were used mainly to carry barrels of cheap Kyrgyz fuel into Tajikistan, but it took about an hour to inspect them. They put me on one of the trucks and we bounced our way down to the junction near Sary Tash, where I got out to hitch a ride west to the border.

|

| The border guards I stayed with. The guy in the middle is the one who loved Halle Berry, while the one on the left is his partner. The truck on the right is the one they put me on to head back down to Sary Tash. |

|

| Looking north towards Tajikistan, with my Halle Berry-loving friend. |

|

| The younger guards. The one on the left spoke English quite well. |

Back on the road to Tajikistan, this time via Karamyk

I was picked up after about a half hour by an old Soviet van being driven by some researchers on their way to Daroot Korgon, and from there I caught a share taxi to the border at Karamyk. Sitting next to me in the back of the car was a uniformed policeman who was obviously drunk, and who insisted I take his picture after I started taking pictures through the car window. He then wanted me to pay him for the privilege of taking his picture, but I just deleted it instead. The other passengers in the car were clearly embarrassed by him. Such is life.

|

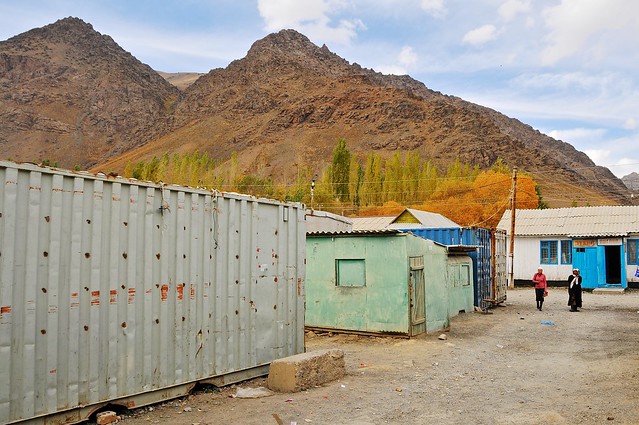

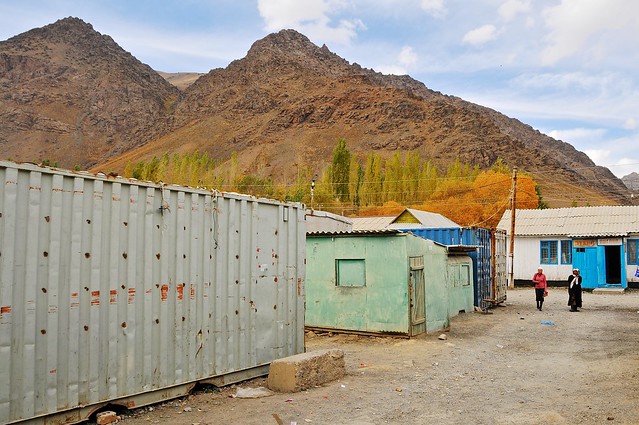

| Container market at Daroot Korgon. |

|

| On our way to Karamyk, between getting hassled by the drunk policeman. |

|

| I'm sure this would be stunning in the middle of summer, when the grass is green. |

The Karamyk border is usually closed, but it was open in response to the unrest in the pamirs. I'm not sure why the border is closed, since it's the most direct way to Dushanbe from Kyrgyzstan. Maybe now that the Tajik side of the road has supposedly been paved the road will be open to tourists, but I don't know. The Kyrgyz side of the border was painless, though the facilities were much more improvisational than they were at Bar-Dobo/Kyzl-Art, with repurposed vehicle bodies being used as official buildings.

|

| Border post. I believe I was actually stamped out of Kyrgyzstan in that structure. |

There's a substantial stretch of no-man's land between the border stations at Karamyk—about 12 km. I don't mind walking (though I had no idea how long the walk would be), and I began to walk the mountainside road between them. I had only just begun when a Kyrgyz guy pulled up beside me and offered me a ride to the Tajik side. It turned out that he wasn't actually going to Tajikistan but simply going to the border to pick up his family, who were returning from Tajikistan.

Welcome to Tajikistan. For realsies this time.

At the border I was quickly stamped in by the Tajik guards, without any unpleasantness or bribe demands. There was a long line of trucks waiting to be stamped into Tajikistan, and the guard told me to wait, and that he would put me on one of the trucks. It took them a long time to process these trucks, however, so I had lots of time to look around on the Tajik side of the border.

|

| Looking down the A372 to Dushanbe. Don't let the paved section fool you: it immediately turns to shit. |

|

| The houses in the village look more hospitable than in Sary Tash. Actual trees! |

|

| The elevation at the border is almost 1,000 meters lower than Sary Tash, as about 2,300 m. |

|

| The skinny little Kyzyl Suu river turns into the Vakhsh as it crosses into Tajikistan. |

|

| Trucks lined up in no-man's land, waiting to be processed at the Tajik side of the border. |

You read in guidebooks how many Tajiks look very European, but you'll also see people like the Uyghur being described as European-looking despite the fact that they only look European to the extent they don't look Han. At the border, however, there was this Tajik guy in blue jeans and a black leather jacket who was a little disheveled but looked for all the world like he could have leapt from an Aki Kaurismaki video, like a down-on-his-luck retro rocker.

|

| View from the road: the husband and a young boy sit on the donkey cart, while the wife walks ahead to open the gate and close it, and otherwise walks behind the cart. |

Rolling with truckers.

Although you sometimes see the A372 to Dushanbe described as the best road between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, it certainly wasn't in my experience. Sure, I was in cargo truck, but most of the road was very coarse stone along narrow roads hugging the side of a mountain, sometimes with boulders from rock slides. We averaged about 25 km/h on these stretches, and it was quite late at night when we pulled into a chaikhana to stop for the night.

By this time we had passed Garm, and had just rejoined the M41 on its run to Dushnabe: it had taken us about 6 hours to cover the 180 km. The food at the chaikhana wasn't bad, but was more of the same Central-Asian fare. I don't think The Hunger Games had even premiered when I left Canada, but a Russian-dubbed DVD of it was playing in the chaikhana. Since I was free-riding with these drivers, I figured the least I could do is pay for dinner, which they allowed me to do. I then slept on the tapchan (with the waiter on another tapchan) while the drivers retreated to the cab to sleep.

The next morning around 6:00 we had a simple breakfast and when paying I asked the chaikhana owner how much I should pay for the bed. He left it up to me, and I offered 20 somoni. He took 10 and gave 10 back.

The drivers were having trouble getting their rig started, however, which gave me time to look around the truckstop in the light, and spent a while roaming around within earshot of the truck.

|

| Pedestrian bridge over the Vakhsh river. |

|

| View from the outhouse, shared by many of the restaurants and chaikhanas at this truck stop. The chaikhana I stayed at is behind me to the right. |

|

| Bridge over the Vakhsh. |

|

| The Vakhsh is joined by the Obikhingou at this point. |

|

| Looking north as the Vakhsh sweeps around the bend from the east. |

|

| Southeast. |

|

| It's a multipurpose bridge, serving cars, trucks, donkey carts, pedestrians, and livestock. |

|

| Slow and slower trundle along this bumpy stretch of M41. |

|

| More of the same. Actually, this road is pretty decent compared to some of the stuff from the day before. |

The fate of truckers: checkstops, bribery, and interrogation

As we trundled on towards Dushanbe I would have to duck down out of sight every time we passed a police checkpoint, as apparently the police are eager to pull trucks over to ask for bribes for any reason. We had to stop and pay random bribes a few times anyway, with most of them being a couple of somoni or so (around 50 cents). As you get closer to Dushanbe the terrain gets flatter, the towns larger and more prosperous, and the roads better. Our bad luck continued as we had a flat tire and had to pull over to repair it, with a minor problem being that we didn't have a repair kit, so one of the drivers had to take a taxi to pick one up.

They were apparently driving from Osh all the way to Afghanistan, and this seemed to be their first time doing this trip. The definite tip-off was the fact that they didn't have a Tajik SIM card, which meant we had to stop on the outskirts of Dushanbe to find a shop to buy a SIM card.

It was around noon when we pulled into Dushanbe proper, where we were stopped by the police at another checkpoint on the M41. I'm still not sure why, but it was something more serious this time, as both drivers had to get out, as did I when the official looked into the cab. I think it was some sort of customs inspection or something, and after a brief conversation we had to go into a large and official ministry building, which—based on Google maps—may have been the offices of Migration Services. Once there the two drivers were taken to an office, and after waiting for a few minutes in the hallway I was taken to another office where I was asked some questions through online translation software. They wanted to know where I was going, what I was doing in Tajikistan, where I had joined the truck, whether I had paid the truckers for the ride, and whether I knew what they were carrying. I answered to the best of my knowledge, and then they sent me on my way by hailing a cab, asking me where I was going to stay (I didn't know but answered the Hotel Poytaht because it was the only hotel name I could remember) and then prepaying the taxi to take me there. I have no idea why we were stopped or what happened to the drivers, but I sure hope it wasn't my presence that got them into trouble.

At any rate, it was an eventful conclusion to a trip that was supposed to end in Murghab 30 hours previously, and ended in showcasing both the best and the worst of Central Asian governance.

Budget

October 9, 2012 from Osh to Kyzyl Art border: 1,610 som

- Seat in share taxi to Murghab: 1,500 som

- Samsa, fried things, cake: 70 som

- Sandwich & 2 x instant coffee packets: 40 som

October 10, 2012, from Kyzyl Art to a truck stop in Tajikistan: $5, 200 som, and 49 somoni

- Ride from Sary Tash turnoff to Daroot Korgon (95 km): $5

- Daroot Korgon to border (38 km): 200 som

- Dinner for three: 39 somoni

- Sleeping on Tapchan at Chaikhana: 10 somoni

No comments:

Post a Comment