As I said in my previous post, share taxis to points north of Dushanbe don't actually leave from the cement factory but from a kilometer or so north of there, where the buses that run along Rudaki turn around (the map below reflects this starting point, which you can see if you zoom in). When I eventually found my way there, I was quickly able to find jeeps going to Penjikent, and negotiated a seat for 90 somoni (almost as much as a seat from Osh to Bishkek, which is about three times longer). Transportation prices in Tajikistan are fairly high, in part because the roads are pretty bad, and in part because fuel is considerably more expensive than in Kyrgyzstan. (You're also more likely to have to bribe a policeman in Tajikistan, too.)

The first stretch of highway as you head north from Dushanbe runs through an increasingly rugged valley that is the backyard for Dushanbe's rich and powerful, who maintain palatial estates along the river. The town of Varzob is possibly the epicenter of ill-gotten wealth, and includes a Presidential retreat complete with imposing fences and security. After Varzob the valley becomes more steep and there are precious few opportunities to build mansions as the road hugs the hills as it wends its way through the Fann Mountains.

|

| The M34 somewhere past Varzob but before the Anzob tunnel. |

|

| Though not particularly high, the Fann Mountains are rocky and support little vegetation. Or maybe it's more accurate to say that whatever vegetation that may have existed has been long since stripped by the peoples who have lived there. |

The M34 between Dushanbe and Khojand is paved from start to finish, with the curious exception of the

Iranian-built Anzob tunnel, also known as the

tunnel of death. Officially opened in 2006, this 5-km-long tunnel bypasses the Anzob pass to the east, allowing the M34 to remain open—and northern Tajikistan connected to thre rest of the country—all year, regardless of the amount of snow in the Anzob pass. The problem is that this tunnel really isn't finished, as the surface inside the tunnel isn't paved, and is potholed and full of water year round as a result of spring-water that leaks into the tunnel from the ceiling. And despite the notoriety of the tunnel through Kyrgyzstan's Too-Ashuu pass, this tunnel is even more poorly ventilated, as there is only one fan in the middle of the tunnel, and its ineffectual whirling does little to clear exhaust fumes from the road. Supposedly the tunnel was to be completed in 2014, but I have difficulty believing that. (

Edit: as of 2018 the tunnel is in good condition, with no potholes or water, and added ventilation, though apparently it can still get pretty polluted in there.)

There are also a number of smaller avalanche sheds along the road leading up to the tunnel, but these kinds of tunnels are much simpler since they are designed simply to protect the road from avalanches by allowing snow to wash over the roof. They're usually pretty short and just cover typical avalanche zones.

|

| After leaving the Anzob tunnel the road switchbacks and hairpins down and around the side of the the mountain. |

|

| Descending from the tunnel. |

|

| The road down below is part of the road leading to the old Anzob pass. |

|

| About to meet up with the old road. |

|

| In some ways the views are familiar to the Rocky Mountains (craggy mountains and aquamarine mountain streams), but the cultivation of tiny scraps of land and the ability to grow fruit trees is utterly alien. |

|

| Absolutely no piece of flat, arable land is allowed to lie fallow. |

|

| A small mountain-slide has necessitated the rebuilding of a valley road. |

|

| There are relatively few villages or patches of vegetation along the north-south M34. |

|

| We stopped at a small restaurant for lunch near the Rabot, not far from the turnoff to Iskander-kul. These kinds of stops are annoying and

inefficient to a Westerner like me, but time has relatively little value

here: why else would people wait hours for share taxis to fill up? |

|

| High tension power lines follow the road. |

|

| A freshly-washed carpet set out to dry. |

|

| Crossing the Zerafshan river in Ayni, only a few kilometers from where the road to Penjikent splits off from the M34. |

|

| It was a bait-and-switch: instead of going over the old suspension bridge (which is the typical bridge design in Tajikistan), this road featured a newer concrete span. |

The rugged Zerafshan Valley landscape: exactly what I had hoped and expected from Central Asia

As we leave the north-south M34 highway that runs between Dushanbe and Khojand, and turn off onto the east-west A377 running through the Zerafshan Valley towards Penjikent, the landscape changes noticeably. The mountains are a warm brown, and the valley is dominated by the Zerafshan River that cuts its way through the mountains, creating steep banks and a ravine-like feeling for much of the valley. Every now and then—mainly when it intersects with side-valleys feeding into the Zerafshan river—the valley widens out into and treed villages pop up. There you find tall poplars and colourful fruit trees showing their autumn colours, softening the otherwise dry, dusty, and harsh landscape. This is the first time outside of China that I've seen the sort of landscape I had been anticipating from Central Asia, and it remains one of my favourite places along my trip.

|

| On the A377 to Penjikent, just outside Ayni. |

|

| We're fairly high above the river. |

|

| Poplars and dusty mountains are kind of what I was hoping the silk road might be like, and the Zerafshan valley delivers. |

|

| The road switches from one side of the river to the other, as some sections are too difficult to build roads on. |

|

| The mouth of every little valley running off the main Zaravshan valley gives rise to a village. The broader the sub-valley, the larger the settlement. |

|

| You can see how the roads are carved into the side of the mountain, with precipitous drop-offs. Passing big trucks on these narrow, stony roads can be nerve-wracking. |

|

| The closer you get to Penjikent, the wider the Zerafshan valley gets and the more fields and houses you see. |

|

| You can see how dusty the roads are. |

|

| Rolling in to Penjikent, near the end of the Zerafshan valley. |

Penjikent

As we entered Penjikent everyone got dropped of at their home. As usual, I was one of the last, and I asked to be dropped at the traffic circle at the western end of Rudaki, as that's where the Elina guesthouse is. It's actually tucked into a little sidestreet, so I didn't immediately see it, and I ducked into a market off Rudaki to get supplies. I came out and then found the Elina after a little searching, and the owner said he had seen me get out of the taxi and had called to me, but I apparently tuned him out.

There are nice little rooms at the Elina that open into a central courtyard, and the shared bathrooms were a lot nicer than those at the Farhang in Dushanbe. At 50 somoni, I thought it was a pretty good deal. The owner is a friendly guy, and he offers tours as well. I'm always a little leery of guesthouses that also offer tours—especially after China—as I tend to suspect that they'll offer less than impartial advice and encourage you (subtly or not) towards their offerings. And since there were two tourist information offices in Penjikent, I decided to direct pretty much all of my tourism-related questions there.

The next day I headed out along Rudaki to explore the city. The Museum (official title: Republican Historical and Regional Museum Named After Rudaki) was close to the Alina and completely unmemorable—literally, as I don't remember a single thing from the interior.

|

| The museum. |

|

| I remember nothing of the museum, which is hardly a ringing endorsement of its contents. but hey, it's not like there much else to do in town. |

|

|

| View from the museum steps. |

|

| The museum's fire station. I feel safer already. |

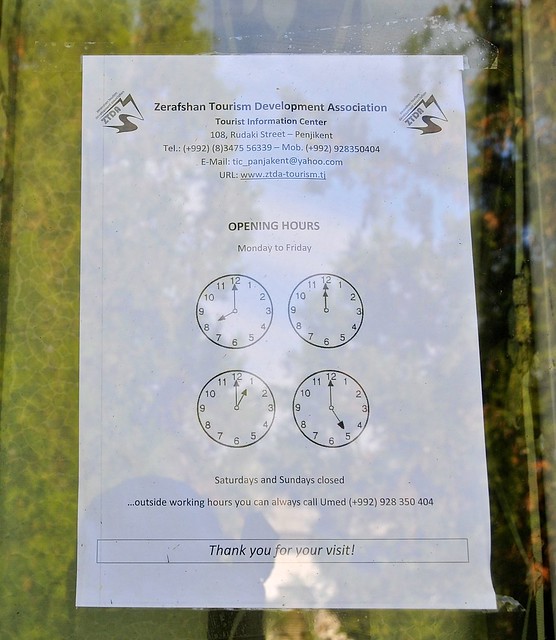

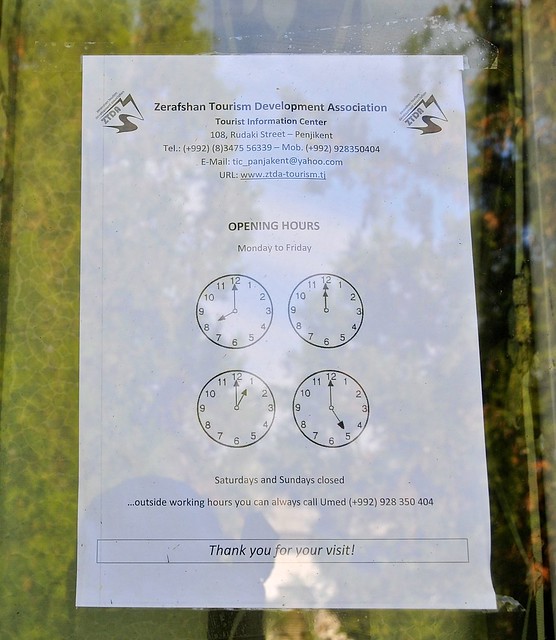

The next stop was the two tourist information offices, both of which are within about a block of each other on Rudaki. On the northern side is the Zerafshan Tourism Board, while on the south side is the ZTDA Information Centre. ZTDA is the Zerafshan valley's version of CBT—a network of homestays and local tourist services that funnel money into local communities. Somewhat surprisingly, they were an inferior source of information about not only independent tourism in the region, but about the homestays they offer as well! In contrast, the Tourism Board office was much more helpful with where one could go, how to get there, the homestays one could stay at, and much more. They also had a number of detailed topographical maps of the area (which I photographed, in case I decided to hike between the valleys), and seemed much more knowledgeable about the area.

|

| In case you want to get in touch with the ZTDA, here's their contact info. |

|

| The ZTB was much better, though, so I would recommend contacting them first. |

I asked about the possibility of starting in the Shing valley and staying at homestays in a Haft-kul (seven lakes) region, and then doing a day hike over the pass to the adjacent valley and down to Zitmud. He was a little pessimistic about this, and his concerns were reasonable given that the days were short and the weather cold. But one concern he voiced—and I heard it from others, too—was that wolves could be a problem. As a Canadian, it seems ridiculous to worry about wolves, but I suspect they are a greater concern to locals who have witnessed their handiwork on their livestock (though I think the availability of lots of goats and sheep makes it even less likely they would ever attack a human). I kept the possibility of crossing from one valley into the next in the back of my mind—the highest pass would only be 3,300 meters—but also acknowledged I would probably not end up doing so (though if I had a GPS I may have felt more comfortable doing so).

|

| Penjikent stadium. |

After the tourist offices I continued east along Rudaki

until I came to the market, which was fairly interesting. As by far the

largest town in the valley, villagers from all along the Zerafshan head

to Penjikent to do their shopping, so you see a lot of people in

traditional rural dress.

I then headed south from the

market through residential districts towards the hill-top ancient city,

which is mainly a large expanse of scrubby dirt, with the occasional low

wall of rammed earth outlining buildings that have long since crumbled,

but there were also a few sections of higher walls and excavated rooms.

A nearby museum contained a number of interesting artefacts in its single room, but in all honesty there's not a lot to capture the imagination or hold your attention.

|

| These ants had worn a path through the straw at the ancient city. These little ant trails were one of the more interesting sights in the archaeological zone. |

|

| Some of the more impressive ruins. |

|

| You have to have a good imagination to picture what this might have looked like a thousand years ago. |

|

| One of the better-preserved excavations. |

|

| View over Penjikent from the northern edge of the archaeological zone. |

|

| Houses are surrounded by walls, making it difficult for a tourist to know what neighborhoods really look like. |

|

| Some walls are extremely impressive (or maybe just extremely new?), hinting at the splendour that may lay behind. |

|

| Interesting Soviet-Tajik movie theater. |

Because people come down from the villages to the market in the morning, and return home in the afternoon, you can really only go to places like the Shing valley in the afternoon. I spent my morning seeing more of the same things I had seen the day before, spending more time at the market. I arranged to leave my bag at the Elina Guesthouse, and left for the mountains with only my camera bag with some toiletries and a few articles of clothing stuffed inside—all the better if I actually decided to hike from one valley to the other.

|

| Buses and share taxis to valley communities leave from the lumber yard just north of Penjikent's market. |

Budget

October 16, 2012, Dushanbe to Penjikent: 162 somoni

- Jeep to Penjikent: 90 somoni

- Bus, 2 samsas, lime drink: 8 somoni

- Naan, tea, lagman: 12 somoni

- Room at Elina Guesthouse: 48 somoni

October 17, Penjikent: 88 somoni

- Internet: 3 somoni

- Dinner: goulash, naan, tea: 12 somoni

- 2 super snickers, cakes: 11.5 somoni

- Museum & ruins: 5 somoni

- 1.5 liter cola: 5 somoni

- Room at Elina Guesthouse: 48 somoni

No comments:

Post a Comment