Finding a share taxi to Osh was significantly more difficult than I

expected. There weren't any at the place indicated in the 2010 Lonely

Planet, and I kind of had to wander around Osh Market until I found a

place with randomly-parked cars half-full with people. Although the

going rate from Osh was only 1,000 som, I ended up paying 1,300 som for

the return trip. It wasn't all bad, though, as I was given the front

seat even though I was the last passenger, and because I was the last

passenger we left right away. It turned out that this was really just a

family returning to their home in Jalal-Abad, and they were picking up a

passenger to help pay for gas.

The car was a Japanese-market, right-hand-drive Lexus. It was about 6 years old, had pretty low mileage, and apparently he only paid something like $6,000 for it. Having lived in Japan, this really isn't that surprising: Japan has an aggressive licensing system known as

shaken that requires cars to undergo inspections every couple of years, and after a couple of inspections it generally becomes cheaper to

sell the cars on the export market than perform the repairs deemed necessary. Of course, because there is a limited market for right-hand-drive vehicles, the resale price is pretty low. Add in the fact that Japanese drive limited distances and take care of their cars pretty well (even if the inspectors feel repairs are warranted), and used Japanese cars are usually a very good deal.

From what I saw on the road, however, it seems that Kyrgyzstan is the only country in the area that allows for the import of right-hand-drive cars (Mongolia also does), which is a good deal for Kyrgyzstanis but a bad deal for others (Kazakhs don't have the same need for cheap cars, Uzbekistan taxes foreign-made cars so heavily that almost all vehicles are made by the domestic Chevrolet factory, and in Tajikistan the market for cheap cars seems to be met by cars stolen from Europe).

Shooting into the sun through a windshield isn't the best way way to take pictures, but it's a heck of a lot better than from the back seat (especially the middle seat, which I had on the way up to Bishkek), and I took advantage of the opportunity on the way south.

|

| The first 60 km from Bishkek you simply head west on a flat road that passes through numerous small villages and towns in the Chuy valley. At Kara Balta you turn south onto the M41, and head towards the Ala Too mountains to the south. |

|

| Passing through Sosnovka village, which marks the entrance to the mountain canyons and the exit from the flat and fertile Chuy valley. |

|

| The steep and narrow valley that the M41 runs through. |

|

| Switchbacks at the end of the valley. |

|

| Who needs road stripes? They wouldn't be obeyed, anyway, as overtaking the slow cargo trucks is a necessity. |

|

| Livestock aren't very good at driving within the lines, either. |

|

| We took a brief break midway up the pass to fill some water bottles from the fresh mountain runoff. |

|

| Looking down the slope at the M41 below. |

|

| Up the northern slope, with fresh snow. |

|

| Our car on the shoulder. |

|

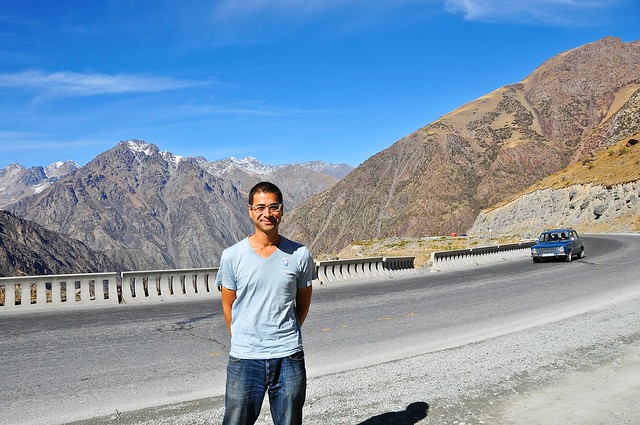

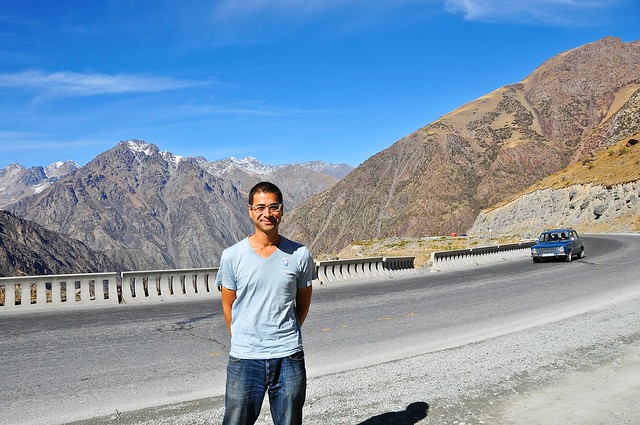

| The driver insisted on taking my picture, which is something I am not normally fond of. My T-shirt was almost white before being laundered with a few pairs of black Uzbek socks. |

|

| Near the peak the mountain opens up into a remote and isolated jailoo—it now makes sense why the livestock had to take the M41 down—before getting steeper again at the very top. |

|

| Switchbacks up the slope. |

|

| These trucks are really slow. |

|

| There's a 2.7 km tunnel through the top of the mountains. This tunnel is poorly ventilated, and in 2001 a few people died of carbon monoxide poisoning when a car stalled and traffic backed up in the tunnel. It's notorious among cyclists, especially the up-hill southbound stretch, and many hitch a ride through the tunnel (or are forced to by the guards). |

|

| One of the final switchbacks. This area was completely free of snow on my way to Bishkek a couple of weeks earlier. |

|

| Leaving the Too Ashuu tunnel, we get our first view over the wide Suusamyr valley. Just to the west of the southern end of the tunnel is a small ski resort, with a solitary chairlift running to the top of the mountain. |

|

| Views over the valley. |

|

| These Kyrgyz yurts are places to buy kumyz and grab something to eat. Coming from the south, it's basically your last chance, as to the north of the pass there are scant high-altitude pastures and the lowland Chuy valley is agricultural. |

|

| On our way down the much gentler, grassy southern slopes of the Ala Too mountains. |

|

| Heading west along the Suusamyr valley. |

|

| As the valley narrows, it also gently climbs, culminating in the easy 3,175 meter Ala-Bel pass at the western end—just barely lower than the much harder 3,180 meter Too Ashuu. |

|

| On the other side of the Ala-Bel pass the snowline shows the drop in altitude. |

|

| Dropping even lower, only the peaks are snowed. |

We stopped for dinner at a roadside diner between the Ala-Bel pass and Toktogul reservoir. At most of these modest establishments the menu is extremely limited, consisting mainly of big

manty mutton dumplings;

shorpo soup with chunks of mutton, potato, and possibly carrot;

lagman nooodles if you're very lucky;

kuurduk mutton chunks with onion and potato; as well as the ubiquitous

choi tea and naan. Even though menus are limited and basically all rely on the same ingredients, they often only have one or two dishes available. I initially asked for lagman. A minute later, word comes back there is no lagman. OK, how about shorpo? A couple of minutes later, no shorpo. OK, what do you have? Manty and kuurduk. Kuurduk it is.

|

| Along the northern edge of the deep-turquoise Toktolgul reservoir. |

|

| The variety in mountains and ranges along the M41 between Bishkek and the Ferghana valley is incredible. |

|

| The Kurpsay hydro-electric dam forms the Toktogul reservoir. |

It was only when we arrived at the turnoff to Jala-Abad that I realized that they weren't actually going to Osh, but that they lived in Jalal-Abad. There are a bunch of restaurants by the turnoff, and we pulled into them. I thought it was a bit strange to stop to eat so close to Osh, but only the driver got out, and the family explained they were going to Osh. The driver found me another share taxi to put me into, paid the driver, and in a couple of minutes I was on my way to Osh and the family was on their way home. It was after 10:00 at night when I arrived in Osh, and I asked to be dropped off at the Taj Mahal hotel.

Sometimes they don't want to let you stay in the dorm at the Taj, and the first time I was there they claimed not to have dorms but only rooms. This is obviously false, but I had no problem checking in to the dorm that night, despite my late arrival.

Budget

October 2, 2012, from Bishkek to Osh: 1,948 som

- Sandwich, coke, snack: 80 som

- Bus to station: 8 som

- Seat in car to Osh, via Jalal-Abad: 1,300 som

- Dinner—kuurduk: 220 som

- Pepsi: 40 som

- Bed at Taj-Mahal hotel: 300 som

No comments:

Post a Comment