The return to Osh brought a welcome increase in temperature. Where the daily highs in the Alay valley were about 5°C, down in Osh—some 2,400 meters lower—the daily highs were right around 20°C.

2010 Osh Riots and ethnic tensions

Back at the Taj Mahal hotel I was joined in the dorm by a couple of journalists from Bishkek. One was a French guy who had come to Bishkek to help set up a French-language newspaper, and the other was a Kyrgyz girl who was working with him at the paper. I was surprised there was enough of a market for a French-language paper in Kyrgyzstan, but he said there was.

Anyway, they were in the Osh to write about the

2010 ethnic violence in the area. Lonely Planet had a little bit of information about this—which was somewhat surprising given that the guidebook was published in 2010 and most of their stuff seems to be written a year in advance of actually publishing it—but the journalists told me that the widespread and severe, and that the interim Kyrgystani government had commissioned an independent report on the violence, and then totally disavowed the report once its highly-critical findings were published. Somewhat strangely, the 2014 edition of LP is even less helpful on the issue, merely saying that the issue was controversial.

I downloaded and began to read the

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry into the events in Southern Kyrgyzstan in June 2010, and I also spoke with the guys at the Osh Guesthouse while reading the 104-page report. At the beginning, some of the things they told me seemed far-fetched, and I suspected they were exaggerating. It turns out their claims were pretty plausible, and I was more surprised after reading the report that their accounts of what happened in 2010 weren't filled with more rancor.

Pretty much everyone agrees that at least 400 people died, and that over two-thirds of those killed were ethnic Uzbeks (others suggest these total represent only a fraction of the actual deaths, given that those buried quickly in accordance with Muslim beliefs were not counted at all). They also agree that over 100,000 international refugees were created, as Uzbeks crossed the border to Uzbekistan

en masse. An additional 300,000 people were internally displaced within Kyrgyzstan—again, almost all of whom were Uzbeks fleeing the violence.

The immediate backdrop for this violence was the

overthrow of President Bakiyev in April 2010, but the longstanding tensions between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan and the Ferghana valley also played a large role: Uzbeks had been marginalized from participation in civil society and employment in governmental positions for a long time, and there was significant resentment of prosperous, urban, Uzbek businessmen from the mountain-dwelling Kyrgyz in southern Kyrgyzstan.

Now in the aftermath of Bakiyev's overthrow, there is widespread belief that Bakiyev and his supporters wanted to foment racial violence in order to demonstrate the need for a strongman-style leader in Kyrgyzstan (as in neighboring CIS countries) who could effectively and ruthlessly control the country. Under this theory, Bakiyev's allies and relatives in the region began to spread rumors about Uzbeks intended to create violence, and Bakiyev thugs may have initiated the violence. We do know that in May, after his April overthrow and exile, Bakiyev supporters took control of

government buildings in Osh, Jala-Abad, and Batken, although

control of these buildings were quickly recovered.

We once again see that tales of inter-ethnic rape is always a reliable way to incite violence. We saw it in the violence targeting Uyghurs in the

Shaoguan Incident in 2009 (which helped spark the Urumqi riots), and it seems to have been the most effective rumor used in June 2010 in southern Kyrgyzstan. After some small skirmishes on June 10, rumors spread of Uzbeks raping Kyrgyz girls at a university dormitory, and it seems that this rumor was spread to Kyrgyz communities in the mountains in an organized manner, prompting numerous Kyrgyz to come down to Osh and Jala-Abad from their mountain communities.

What seems to have happened after this is that Kyrgyz streamed into Osh and Jalal-Abad, and that the Uzbeks largely barricaded themselves into their districts in order to protect themselves. The arriving Kyrgyz then raided police stations and security vehicles that had been deployed by the police, seizing weapons and ammunition from these forces, who did not attempt to prevent them from doing so. Apparently a few Armed Personnel Carriers were also taken from the complicit police, and used to help break into Uzbek areas: direct military involvement seems probable.

Applying its evidentiary standard to the evidence, the KIC considers that there was some military involvement in these attacks. This arises from presence of expertly driven APCs carrying men in military uniform, the apparent readiness with which the military surrendered APCs, weapons and ammunition, the repeated system and order to the attacks and the evidence of planning in the specific targeting of neighbourhoods, people and property. Such discipline and order is not commensurate with the normal actions of spontaneously rioting civilian crowds.

Women were seized and raped, while men were tortured and killed. Police sniper rifles were also used against Uzbeks, though it's not certain if these were from civilians who had seized the weapons or from actual police or army officers. Those Uzbeks who could sought refuge across the border in Uzbekistan, while others fled their homes to seek refuge elsewhere in Kyrgyzstan.

Once the situation stabilized and peace returned to the area, almost all of those who were investigated and charged with violence were Uzbeks, and police failed to protect those Uzbeks from physical assault during their trials. It's clear that ethnic tensions continue to percolate in the region.

This happened only two years before I was in Osh and Jalal-Abad. Although many buildings had been burned out, I had failed to notice any, and if I did notice any I certainly didn't connect them to the violence. For someone coming from a stable and diverse country like Canada, it was really difficult for me to understand this level of ethnic strife, and to understand how people could continue to function as a society in the knowledge that there was so much widespread ethnic hatred which could be re-ignited at any moment. It was difficult to understand why there wasn't more anger from the Uzbeks. I'm sure that part of it is that as a tourist you simply aren't able to access and understand the tensions that simmer beneath the surface in most societies (I'm not sure that most tourists to the US really feel the the tense state of race relations there, even though events continually pop up that hint just how bad they are), but even accounting for this there simply seems to be a greater acceptance of—or resignation to—tremendous injustice, discrimination, and unfairness.

About the Osh Guesthouse and the guys that run it

Talking to the guys at the guesthouse about these issues was really quite interesting. They willingly and openly spoke about religion and Uzbek culture. Both of the guys were in their twenties. One was quite conservative and had a full beard and dressed in a robe, but was also quite progressive and open in a lot of ways (as you would have to be if you worked with Western tourists) with a love of gadget-laden digital watches. The other was also religious even though he wore jeans and T-shirts, and already had three kids in his mid twenties. The surprise—to me, at least—was that he had two wives. I was kind of shocked that this was allowed, especially given the country's Soviet history, but he said it was actually fairly common in practice even during the Soviet era. Only one of the marriages was a legal, government-recognized union, with subsequent marriages being only religiously-recognized.

For him—as for most Central Asians—Westerner travelers are a little weird in that we tend to be fairly old, mainly single, have little interest in having children, let alone many children. This isn't to say that all Central Asians want lots of kids—many don't—but pretty much all of them want at least one or two.

In more pedestrian news, I was able to pick up my GBAO permit from the Osh Guesthouse, meaning that I was set to head to Murghab, Tajikistan. The other news was that the guesthouse had received notice from the post office that they had a package, and when they picked it up it turned out to be my replacement boots from Blundstone Australia! Amazing service.

Transport to Murghab can be rather challenging, especially in of season. Osh Guesthouse can arrange travel, but this is mainly in chartering a vehicle. They'll put you together with other travelers, but you're still paying for the entire car and unless you can fill it up with 6 people, you'll end up paying more than if you can get a seat in a normal share taxi.

As I've said before, Osh Guesthouse is best used as a place to meet other tourists, and not necessarily to stay there (this is especially true now that a number of other fully-equipped guesthouses have opened up in Osh). And while the guesthouse also maintains a whiteboard where you can leave messages for other travelers and try to find travel partners, the guesthouse requires that all contact information be left with them. This ensures that transportation bookings go through them, and makes it more difficult to arrange for independent chartering (it is possible to book for cheaper than you can get through them).

After getting my stuff from the Osh Guesthouse I visited local share-taxi stands to see if I could find anything leaving for Murghab the next day, but was unable to find anything. Then I wandered through the market some more before heading up to Sulaiman Too for another evening visit.

|

| Dog trying to catch some sleep in the market. |

One of the things I talked about with the guys from Bishkek was how cheap produce generally was, and about how tomatoes had increased in price since my last time in Osh (they went up from about 10 som per kilogram to 18 som per kilogram). They said that in Bishkek they have an unofficial tomato index that fluctuates heavily based on the season, ranging from 10 som to well over 50 som in the winter. It's easy to take things like that for granted when living in the West, where everyday food may have been grown thousands of kilometers away, and as abundant as fruits and vegetables are in Central Asia during the summer and autumn, availability is purely seasonal.

|

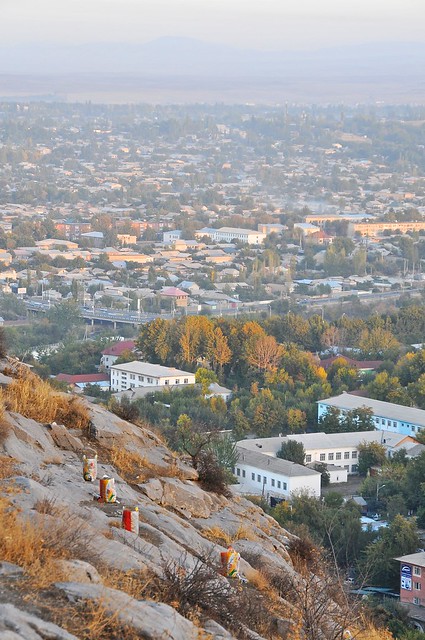

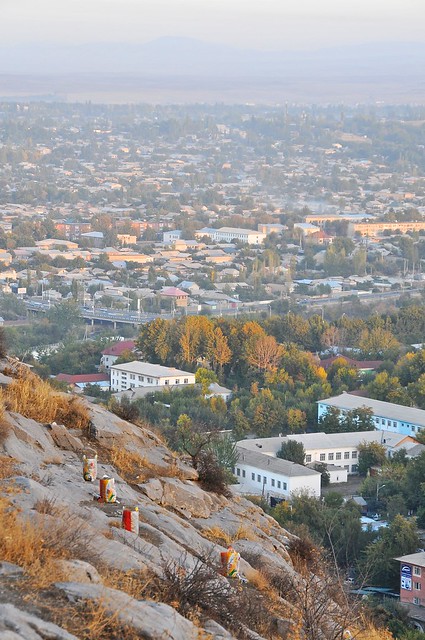

| Only the peaks are visible through the smog south of Osh, as seen from Sulaiman Too. |

|

| A little later, a little clearer. |

|

| West into the sunset. |

|

| Looking southeast. |

|

| It's a lot easier to climb to the top of the mountains on Sulaiman Too if you approach from the north, as the slopes are much gentler. |

|

| South from one of the peaks. |

|

| That next mountain is in Uzbekistan. |

|

| The Uzbek border is right at the edge of Osh, and you can take a city marshrutka there. |

|

| Looking northwest, out over Osh and Uzbekistan. |

|

| Burning brush and industrial emissions help make the Ferghana valley notoriously smoggy, while the surrounding mountains help trap it in the valley. |

|

| Sexy lady petroglyphs. I'm surprised we don't see more of these in ancient cave art, as opposed to deer and animals. |

|

| Women clean the slopes of the mountain, presumably for religious merit, collecting debris and trash in large sacks. |

|

| One of the fertility-inducing rock slides that predate the advent of Islam. |

|

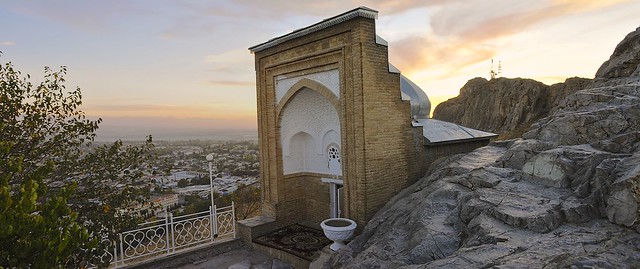

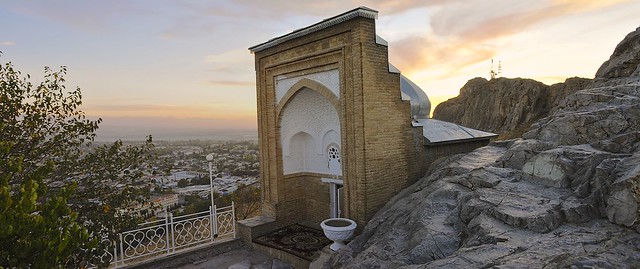

| Babar's mosque at sunset. |

|

| A great guy at a great (and cheap) snack place, on the southeastern corner of the mosque. Every time he saw me I got a hearty "Hey, Canada!" greeting. |

When I went down to the Agromak 4WD taxi stand, and told touts and drivers that I wanted to go to Murghab,

everyone offered to drive me there. Most offers came down to $150 for

the entire car, but one guy with a recent Mercedes E-class station wagon

went as low as $100, saying we could leave immediately and I could

sleep in the car since I would be able to fully recline the front seat.

I'm sure he would have picked up additional passengers and/or cargo, but

this is a screaming deal to Murghab, considering the Osh Guesthouse

would charge about $250 for a car there and a single seat in a share

taxi is 1,500 som (about $30).

I was to cheap for

that, and since I couldn't find anyone going to Murghab from the Agromak

stand (I think most had moved to the Murghab station outside of town,

though this information wasn't widely known at the time) I figured I

would instead get a ride to Sary Tash and then try to get something to Murghab from there. In retrospect, this would have been a terrible idea, as vehicles to Murghab tend to leave from Osh, not Sary Tash, and be completely full when they leave Osh.

Anyway, I had already agreed to go in a van and was waiting hours for it to fill up, when I started wandering around the Agromak stand while waiting. I then saw a jeep with a sign for Murghab in its window, and I decided to pull out of my van to Sary Tash (much to the disappointment of the driver ad other passengers also waiting for the van to fill up). I met the jeep driver as he was walking back, and he said that we should be able to pick me up the next morning, and that he would pick me up at around 8:00 at my place at the Taj Mahal. Fantastic. Even better, he quoted me the correct local price of 1,500 som, meaning no bargaining was required. (This kind of honest approach makes me wonder how much I should be bargaining, or perhaps lulls me into a false sense of security with other drivers.)

|

| The sign for a Murghab bound jeep, as seen in the Agromak 4WD lot. Try contacting the driver, who does the run regularly: he's friendly and honest! |

|

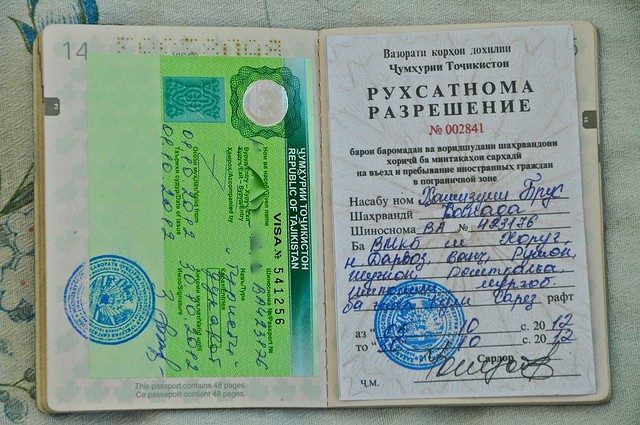

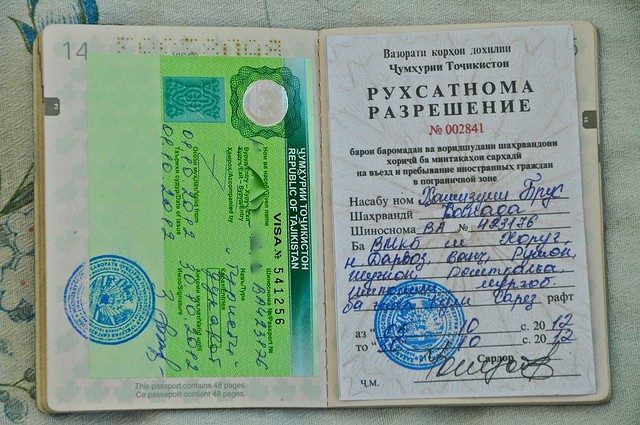

| My Tajik visa and the GBAO permit. For a document scanned in Dushanbe and printed in Osh, it felt surprisingly authentic. |

Budget

October 6, 2012 from Sary Tash to Osh: 987

- Room: at Taj-Mahal: 300 som

- Soups: 30 som

- Taxi to Osh: 430 som

- Chocolate, eggs, coke, sandwich, soup: 205 som

- Tomatoes: 22 som

October 7, Osh: 960

- Room: 300 som

- Candy: 120 som

- Sandwich, samsa, kefir, Hall's lozenges

- Eggs, tomatoes, apples: 100 som

- Shashlyk, kebab, naan: 90 som

- Blackberry jam, chocolate x 2, coke: 210 som

- Internet: 40 som

October 8, Osh: 569 som

- Ak Telpak felt hat: 100 som

- Samsa, 3 x meat pastry: 40 som

- Room at Taj Mahal: 300 som

- Coke, tissues, pastry: 64 som

- Ice cream, coke: 45

- Solomon Throne entrance: 20 som

No comments:

Post a Comment