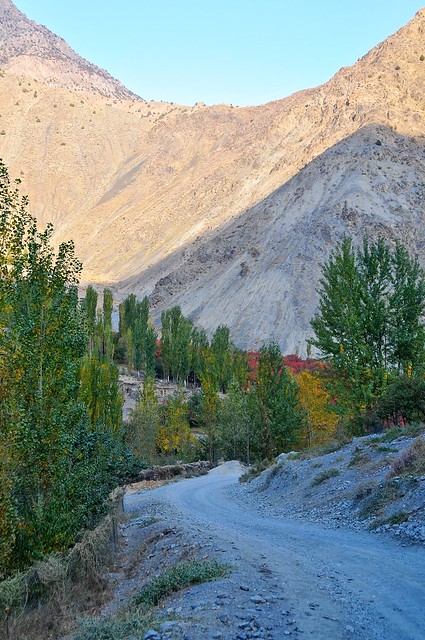

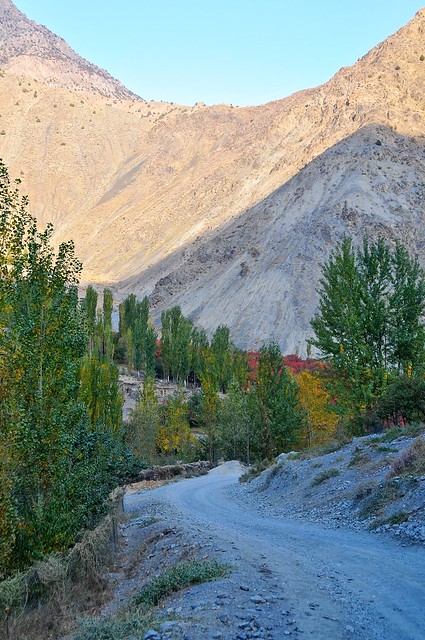

Walking down the valley to Shing

I woke up early in the morning to be on the road by 6:00, which is supposedly when vehicles went down to Penjikent. After waiting by the main road in the darkness with Jumaboy for a while, it became fairly clear that whatever vehicles there were had already left, so I started to walk down the valley in the crisp morning air.

|

| By 6:45 the sun was up and I was on my way down the valley. |

|

| Everything looks so different in the shade as opposed to the sun. |

|

| Lake 3, with lake 2 behind it. |

|

| Colours are warming up as the sun rises higher and the clouds make soft light, as I look back at the second lake. |

|

| The first lake at 7:45 am. |

|

| I can't get over the crazy clarity and colour of the water here. |

|

| Crystal clear or inky black? |

|

| An old man walks on a side path bypassing the switchbacks. |

|

| The morraine damming the end of the lake. |

|

| Such stark beauty. |

|

| The outlet from the first lake. |

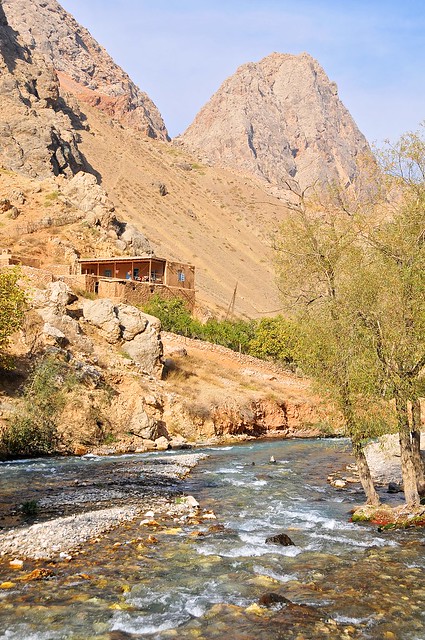

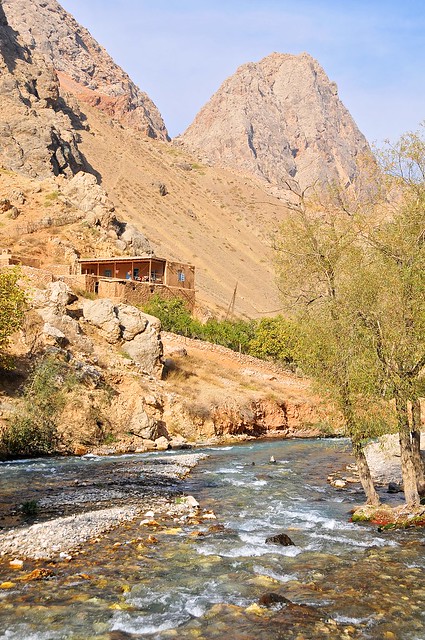

After the first of the seven lakes, with no more lakes or wide valleys in which villages can form, there are more houses directly alongside the stream. It was in one of these stream-side villages that I saw a rare sign of international aid: a simple water spigot bearing an NGO's logo. Aside from a similar water spigot north of Sary Tash, this was really the only evidence of international aid in the most impoverished communities that need it most; for the most part you see international aid spending in the capitals and larger cities.

Of course this overlooks NGO-sponsored community-based

tourism initiatives like CBT in Kyrgyzstan or ZTDA in the Fann

Mountains, but I'm not sure how much they benefit the entire community.

Sure, those families who are able to participate benefit, but I suspect

that most participants are already relatively wealthy members of their

villages, while those who are most needy simply can't participate.

That's not to say they aren't helpful, but I don't know how widely they

benefit the community (as opposed to infrastructure projects like

spigots). On the other hand, they are much better than the Han-run

hostels and hotels that dominate Xinjiang: there, you're not benefiting

any locals—wealthy or otherwise— but migrant exploiters.

|

| Below the lakes the Shing Valley is much more of a canyon. |

|

| Whenever the valley widens even a little you find patches of trees and houses. |

|

| A rare sign of international aid. but when you see the opulence of Rahmon's Dushanbe, you have to wonder why most of the country lives like this. |

|

| Need a bridge? Just turn the beds of some old trucks upside down. |

|

| Rugged beauty. |

|

| Villages are like oases in deserts. |

|

| Dust rises from a rock-crushing gravel factory in a small side valley. |

|

| A cave is used as an animal pen, with hay stacked out of the animals' reach. |

|

| Dusty tree in a stream. |

|

| The river widens near Shing. It was 9:15 by the time I arrived there. |

|

| You don't often see women carrying loads on their heads. |

It took more than two hours for me to make my way down to Shing.

I waited for a while in the parking lot in front of the market there,

but since I didn't see anyone else waiting around or vehicles waiting

for passengers, I decided to keep walking down the road and to try my

luck hitching with cars going down the road. After a half hour or so of

walking, I was picked up by a car going down the road, and they accepted

I wanted to go to Penjikent and we agreed on a price. I'm not quite

sure why this happens, but they were actually only going halfway to

Penjikent, which inevitably leads to disagreements about what I should

pay. I paid about half, and was able to quickly get a new ride in this

larger town from a couple of guys going to Penjikent. The cheerful

driver and his passenger obviously knew each other and were friends, and

we left without waiting for the car to fill up. When they dropped me

off they hopefully asked for extra money, but didn't mind when I declined.

|

| A mountain bus parked in front of the market in Shing. I wonder where it's going, as it's a bit of overkill for the road between Shing and Penjikent. |

|

| Bringing home the hay. |

|

| To me this house is evocative of a vacation home in a Mediterranean country, but I think the living conditions are just a tad different. |

|

| There are a surprising number of trees in streams and rivers. I wonder if their location isn't what protects them from being cut down for firewood, as trees seem to be either on private property or in streams. |

|

| Walking down from Shing. I was picked up about a kilometer from there, as the road joined with another from a different valley to the left. This picture is from around 10:30, and I arived back in Penjikent at around noon. |

When I went to collect my bag from the Alina Guesthouse, I spoke with the owner, who asked me how my trip was and where I stayed. When I said I stayed at the CBT homestays in Padrud and then Nofin—and that the Padrud one really sucked—he was surprised, as he said he knew the owner of the Padrud homestay and that he was away in Khojand visiting relatives He even tried to phone him, but wasn't able to get through to him. He figured that the guy I stayed with must have been his brother, which would explain why the experience was so crappy. I probably should have spoken to him before I set out, but I was worried about being pressured into buying/booking something through him.

|

| A rather attractive Soviet-era statue. |

After picking up my stuff I hopped onto a marshrutka headed to the market, and the walked east from there towards the taxi point for Dushanbe. I paid 90 somoni to get to Penjikent from Dushanbe, and even though I know some locals who paid more, I still though 80 was a reasonable rate. The first driver who approached wouldn't go that low, and as I moved on to the next cluster of drivers I was approached by a young guy who had been listening in. He said that he would take me for 80 somoni, and it turned out that he was just a guy who was visiting Penjikent with a friend and he wanted to get some extra money on the trip back. This was great, as we ended up leaving with only 4 people in the car, which meant more space and less waiting for the car to fill. Even better, we didn't make any restaurant stops along the way (which reinforces my belief that professional drivers get some sort of kickback or comped meals from the places they stop at).

|

| On the road back to Dushanbe, over the bumpy but beautiful A377 through the Zerafshan Valley. |

|

| It remains one of the most scenic roads I encountered on my trip: you certainly feel you are in another word, another century. |

|

| And how so many people scrape by on so little will remain a mystery to me. |

|

| Passing trucks on these narrow roads can be a bit scary when you're in a car, and in some places one vehicle has to stop in a wider area and let the other vehicle through... but if it's one truck passing another it must be a tight squeeze even there. |

|

| Can you guess where a stream runs? |

|

| View of Novdunak. Every patch of reasonably flat land is inhabited and/or cultivated. |

|

| Just outside Novdunak, on a very narrow stretch of road. |

|

| The village of Zerabad, just 3 km from Novdunak on the opposite side of the river. |

Back in Dushanbe, I checked back into the Farhang. Not as nice or central as the homestay, perhaps, but significantly cheaper, and with the assurance of a bit more privacy.

The next day was obviously centered around buying a plane ticket. There's not a lot to do in Dushanbe, anyway, so I mainly walked around enjoying the city and grabbing lunchtime plov at the market—probably my favourite meal in Central Asia, and certainly the best deal—before heading over to the Tajik Air office in the afternoon for more wrangling.

Round two in the battle to get a ticket on the flight to Khorog

I arrived at the ticket office and the same girl I spoke with earlier told me to come back in a day or so. I reminded her that I had been there the week before and she told me to come back that day. I don't know if she remembered or not, but she relented and told me to come back in the afternoon, around 5:00.

I left and headed up to the Turkmen Embassy to pick up my transit visa. Once again I went through the routine of checking in with the security guards at their hut in the alley outside the embassy, waiting for them to phone in your arrival to the embassy, and then siting on the bench outside until summoned into the embassy compound.This time I got a glimpse inside of the security guards's hut while they stopped to chat with an elderly local man, and was saddened to see that they basically seem to live in their tiny shack: there was a small bed running the entire length of the room, as well as a small stove and cooking equipment.

Anyway, when I was summoned to the consulate's office, he cheerfully asked me if I wanted to modify my transit dates, then quickly printed of my visa when I said the prior dates would be fine (there wasn't much to think about, as I wanted to use all of the days on my already-running Uzbek visa, and enter Turkmenistan as late as possible). Like pretty much everyone who applies through Dushanbe, I received the full five days, as well as the entry and exit ports requested. Not everyone is so lucky at other embassies, and when you add in the ability to modify your dates when you pick your visa up (within reason, I'm sure), Dushanbe is a terrific place to get your Turkmen transit visa.

When I returned to the Tajik Air office in the afternoon, there were more people waiting there, which is a good sign. After a bit of waiting the girl took my passport—another good sign—and then I settled in to wait with a few locals. One of them struck up a conversation, and it turned out that he was a Pamiri from Khorog who ran an art gallery there. We talked a bit about the difficulty of getting tickets, and he said that most Tajiks would also prefer to fly, especially since flying was not much more expensive than taking a share taxi, and could even be cheaper depending on the season. It turns out that the passenger traffic to Khorog is highly seasonal, with lots of students headed to Dushanbe in the fall and then returning home in the spring, so that if you wanted to go in a high-demand direction during the busy season it could be more expensive to drive than fly. But with limited passenger space on the planes and substantial uncertainty whether any given flight will even leave, it's easier to count on taking a share taxi.

Anyway, I was eventually able to plunk down my 440 somoni for my flight, and receive in return the paper tickets with red carbon, just like we used to use last century (my god, it feels strange to write that!). Now the only thing I had to worry about was getting up before dawn and making it to the airport for the indicated 6:30 departure time.

Budget

October 21, 2012, Padrud to Dushanbe: 208 somoni

- Breakfast: 10 somoni

- Taxi to Penjikent: 20 somoni

- Marshrutka within Penjikent: 1 somoni

- Taxi to Dushanbe: 80 somoni

- Cola, cakes: 15 somoni

- Ice cream, soup, soda: 5 somoni

- Dinner: 17 somoni

- Room at Farhang: 60 somoni

October 22, Dushanbe: 109 somoni, $55

- Turkmen visa: $55

- Plov (with bread and salad) at market: 4 somoni

- Dinner: 26 somoni

- Cola, ice cream, nuts: 10 somoni

- Popcorn: 1 somoni

- Buses: 8 somoni

- Room at Farhang: 60 somoni

No comments:

Post a Comment