About Haftkul and the Shing Valley

The rugged Fann Mountains that line the southern side of the Zerafshan Valley are home to

a number of gorgeous lakes, as well as lots of hiking opportunities. And although many of the lakes really require you to hike in and stay at Soviet-era Alpager camps, tent camps, and/or your own tent, the Haftkul (literally, "seven lakes")—also known as the Marguzor Lakes, after the largest of the seven lakes—in the Shing Valley are a relatively accessible way to dip your toes in the Fann Mountains. Buses to Shing (located below the seven lakes) run daily, as do share taxis to villages further up the valley. Because traffic is dominated by valley-dwellers who go down to the market in Panjikent in the mornings and return home in the afternoon, you can spend the morning in Penjikent (which is really all the time you need to see it) before going up into the mountains.

Making life even easier for the visitor is that there are a number of established ZTDA homestays in the valley, which assures you that you'll be able to find a place to stay. In all honesty, even if there weren't homestays you could probably find a place to stay in any village in the mountains, as locals will welcome you if you look like you need a place to stay (and probably even if you don't). Just be sure to offer them some money when you leave, and insist they take it (or pass it to a daughter if they really refuse), especially if they don't seem rich.

While I would have liked to have seen some of the more remote lakes, I was in the shoulder season and I didn't have a lot of time to extend my stay in the region (I wanted to be back in Dushanbe to pick up my Turkmen visa as soon as it was ready, as I had limited time on both my Tajik and Uzbek visas), so I decided to take things easy and head to the Shing Valley—while being open to crossing over to the next valley if it seemed reasonable. And to facilitate any hiking I might do, I arranged to leave my bag at the Elina Guesthouse and take only my camera bag and a change of clothes into the mountains with me.

Afternoon arrival & preliminary explorations

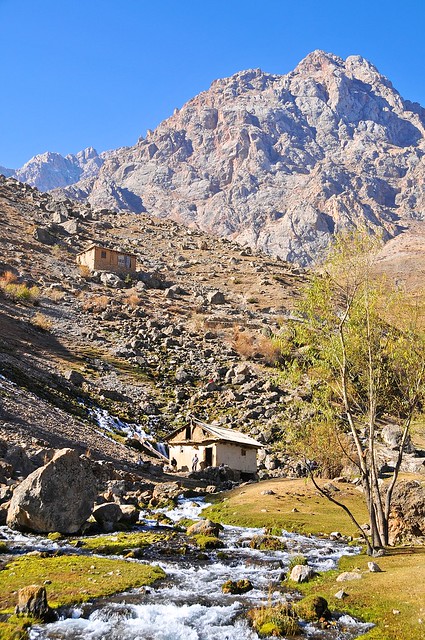

I ended up getting a share taxi from the lumber yard in Penjikent, and they were able to take me all the way to the uppermost ZTDA homestay settlement of Padrud. The Shing Valley starts just to the east of Penjikent, and as you head south up the valley the communities become smaller and smaller, and the road gives way to gravel and then becomes rougher and rougher.

The introduction to the seven lakes is a doozy, as the lowest of the seven lakes has an incredibly clear yet blue colour, and at the end of the lake you enter a series of rocky switchbacks as you pick your way up the rocky natural dams that separate the lakes. Although all of the lakes have been formed by rock dams, I'm not sure if these are the result of landslides (the highest dam in the world—the 567 meter high

Usoi damn in the Tajik Pamirs—was formed by an earthquake in 1911) or as the result of glacial rock deposits known as moraines. I suspect moraines.

Those switchbacks are probably the most dramatic section of road in the entire valley, and they lead up to the second and third lakes, which are almost on the same level and are quite close to one another. After that, it's a couple of switchbacks up the the 1.6-km-long fourth lake, the southern end of which is where Nofin is located, and then up the valley towards Padrud, which is located on the rocky dam that forms the fifth lake.

On the way up to Padrud I discovered that one of the guys in the taxi ran the Padrud homestay, which was a bit lucky. We got dropped off outside the homestay, but the gate around the compound was locked, so he had to go retrieve a key from somewhere. In retrospect this is a bit weird, but I didn't think anything of it.

When we entered the house it was a bit weirder, as the table and living area was dirty, with peanut shells, crumbs, and candy wrappers on a greasy table next to the ZTDA folders and price lists, and the host did nothing to even try and tidy up or anything. Whatever. I was just interested in dropping off the change of clothes and toiletries I didn't want to carry with me, so I let the host know that I would like to also order dinner for that evening, and then I headed out to explore.

|

| Walking up the hill toward the tiny fifth lake, Hurdak. |

|

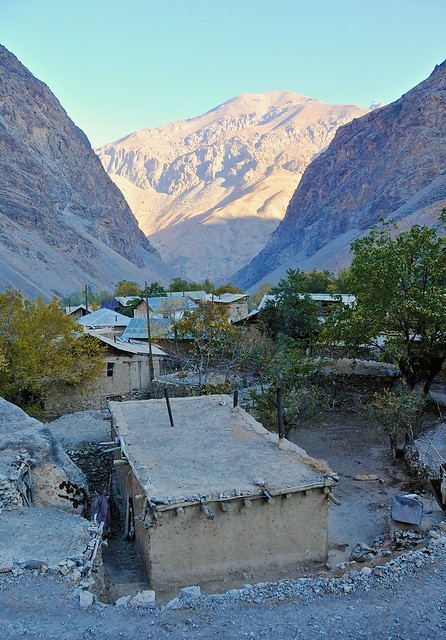

| Near the top of Padrud village. |

|

| This freshly-washed carpet isn't likely to dry very quickly in this weather. |

|

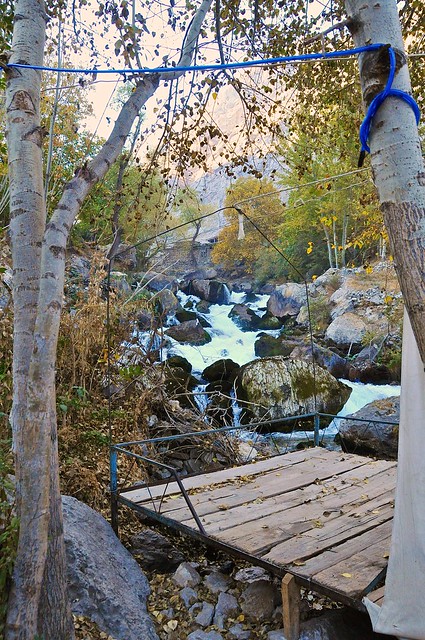

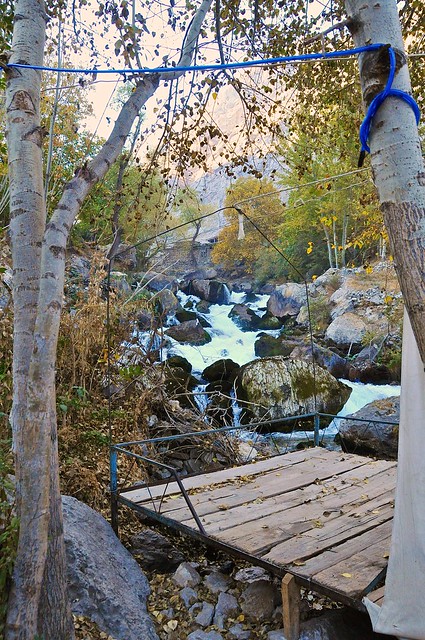

| Rickety little bridge near the outlet of the fifth lake. |

|

| Circles of cow dung stuck against a rock to dry. I wonder how many trees the mountains could support in the absence of man. Probably quite a few. The lack of anthropogenic deforestation really makes the Rocky Mountains I'm used to look very different than these sorts of mountains. |

|

| The road up from the fifth to the sixth lake. |

|

| Looking down towards Padrud over the little dot of the fifth lake, surrounded by steep mountains. |

|

| Cows making their way down to the lake. |

|

| Looking back

as I walk the road along the sixth lake, Marguzor. In the middle of the

picture you can see four or five tourist cabins built on the southern

shore of Marguzor. |

|

| Looking north along the edge of Marguzor. You can see the high rocky dam that formed the seventh lake. |

|

| Looking up at a mountain that still enjoys the sun. |

|

| Panorama of Marguzor. |

|

| The end of the sixth lake. You can see how much higher the water has been in the past. |

|

| Looking east. If I wanted to hike to the next valley, the pass would be up at the end of this side valley. |

|

| Looking down at Marguzor. |

|

| 5:45 and there's almost no useful daylight left as I walk along Marguzor Lake back towards Padrud. |

Padrud: worst homestay ever?

The homestay wasn't any cleaner that evening when I arrived, and "dinner" was one of the worst meals I had anywhere on my trip—and certainly the worst value for money.

In general, prices in Central Asia aren't as cheap as you might expect—and certainly much more expensive than in Southeast Asia for a lower standard of food/accommodation—with even basic menu items like shorpo or manty usually being at least a couple of dollars and basic accommodation being ten dollars or more. Prices at official homestays are usually fairly high (the standard in Tajikistan seems to be $10 for bed and breakfast, and $5 for dinner), but they also pay 15% to the organizing NGO which ideally provides support, advertising, training, and applies standards so that tourists get a reasonably consistent and professional experience. (One of the things that the ZTDA seems to look for is a large housing compound with green space, which unfortunately seems to limit opportunities to those that are already somewhat prosperous.)

At this homestay, however, things were seriously off the rails. Dinner consisted of some old barley unceremoniously scraped from a pot and dumped on a plate, supplemented by a chunk of meat, and served with a small pot of tea (that wasn't refilled). Strangely, the host dined with me (hosts usually leave guests alone while they eat), eating directly out of the pot and using his fingers to scrape up the barley and grease remaining in the pot. Even though I find the typical five-dollar price for meals to be somewhat steep (and more than I would pay if not eating elsewhere), they are typically pretty decent meals with a variety of dishes. I was really shocked by this meal, and was surprised when he actually charged me the full $5 for this horrible meal which I would expect to pay maybe one dollar at a restaurant.

After eating he showed me to the guest room, which was basically a large but dark room under the main room in the house, filled with kurpacha mattresses stacked against a wall. Like most homestays, here was a long-drop outhouse building a short walk away, and a hot-water shower in another building. Showers are easier to provide than toilets, as you just need an electric hot water tank mounted next to the ceiling, with a gravity-fed shower head running from it. Floors tend to be rough cement or even a wooden platform over bare dirt, and runoff water simply escapes outside or into the garden.

Anyway, after dinner I had a shower, settled into bed in the unheated room and watched a movie or two while wondering how the hell this homestay ever received certification from ZTDA.

In the morning the breakfast was simple, with bread, tea, and an egg. After the night before, I wasn't expecting much, and although I had considered using Padrud as a base, I had easily made the decision to move to a different homestay that evening... and I understood why the helpful guy at the Zerafshan tourist information had recommended staying with Jumaboy in Nofin instead of the better-located Padrud homestay.

|

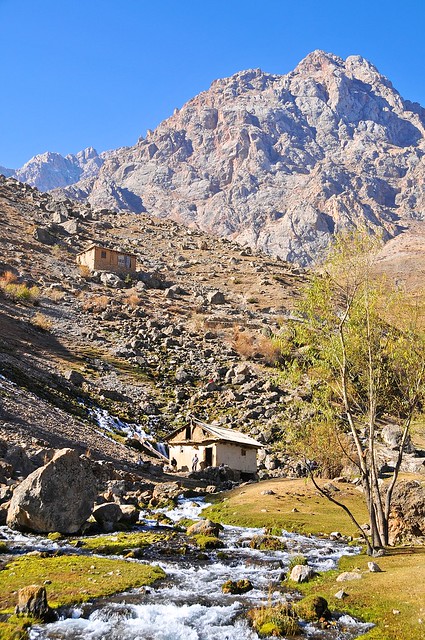

| River-side tapchan tea bed at the Padrud homestay. I'm sure it would be idyllic in summer evenings. |

|

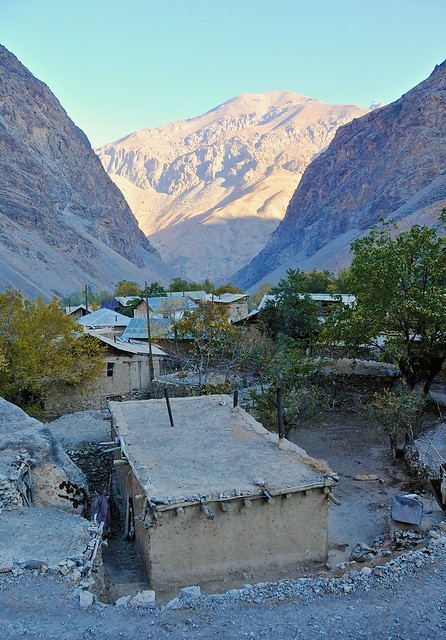

| Looking down over Padrud. |

|

| Kids near the local school want their picture taken. |

|

| Striking a pose. |

|

| Approaching the fifth lake, Hurdak. |

|

| Unfinished houses. |

|

| Hurdak lake. It may not look it, but the mountains are right on top of you, and I only got this image by zooming all the way out to 18mm, shooting in portrait, and then stitching five images together to make this panorama. |

|

| Marguzor is the largest of the seven lakes, at about 1.7 km long. |

|

| A village next to Maruzor. On the left you can see the high natural dam forming the seventh lake. |

|

| You see many more donkeys than motor vehicles roaming these roads. |

|

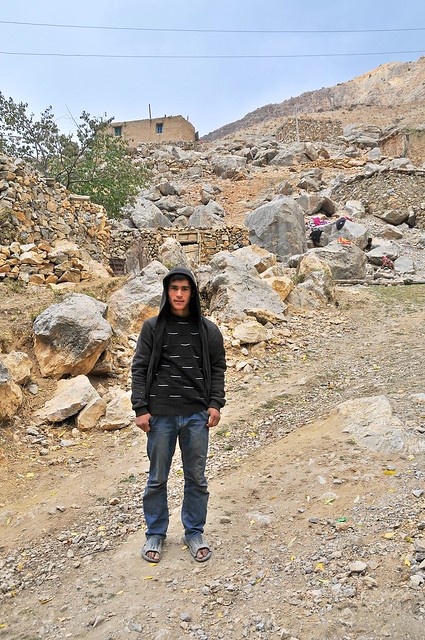

| Man and mountain in perspective. |

|

| Roads are blasted through the mountain sides, resulting in rocky overhangs. Thankfully there isn't much vehicle traffic, as spots to pass are rare. |

|

| Looking back at the lake. |

|

| The broad inlet to the lake, which looks like it would historically be covered in water. Possibly it is every spring, when the meltwater is at its highest? |

|

| It says something about the modernity of the region that the 50-year-old truck is the less common form of transport shown in this picture. |

|

| Looking up the northern slope of side valley that would lead to the neighboring valley. |

|

| Lots of houses, but little visible means of sustenance. |

|

| The Holonichiston river as it flows between the seventh and sixth lakes. |

|

| I was surprised at how close this house was to the waters that came within feet of its walls, at the base of the natural dam. |

|

| Looking back down the valley. |

|

| Everyone, everywhere, loves some graffiti. If they're old enough, you get to call them petroglyphs. |

|

| There are houses just about everywhere you can imagine houses being built, and many even where you can't. The same thing goes for fields. |

|

| The nice thing is that all the lakes are connected by road, which means none of the walk is overly steep or a difficult scramble. |

|

| Lone house by Hazorchasma, the seventh lake. |

|

| Rocky beach at the end of the lake. |

|

| The road ends at the outlet of lake seven, and from there you have to follow a narrow footpath around the western edge of the lake. |

|

| Along the path. |

|

| Just like the rocky road down-valley is more scenic than a modern sealed road, this stony path is more scenic again. |

|

| Partway along the lake. |

|

| Shelter near the upper end of the lake. |

|

| Young family taking their livestock down the valley. The girl instinctively left the scene when I went to take their picture, and I had to assure her that I wanted her in it, too. |

|

| Donkeys carrying loads of alpine hay down the valley for the winter. |

|

| The harder the life, the more picturesque it is to our eyes. |

|

| Bridge over the inlet to the seventh lake. |

|

| Livestock pens at the top of the lake. The Uzbek border is only a few kilometers away, at the top of the mountains at the end of this valley. |

|

| Stone cairn near the pens. |

|

| Starting my way back down the lake. I considered heading further upstream, and taking the path you can see on the other side of the lake that curves around into the valley to the left, but decided that if I wanted to see all the lakes that day I had best not push any farther. |

|

| At about the midway point of the lake. The water level in this lake seems about as high as ever. |

|

| On my way back down the lake I encountered this old man and his son. |

|

| The son trying out my camera. It's around noon and sunny, but still a bit chilly. |

|

| The old man makes his way up the lake. |

|

| From a shaded portion of the trail. |

|

| Where the road ends: in a meadow next to the seventh lake. |

|

| The outlet passes through the meadow before going down the rocky dam. |

|

| Lets cultivate some land in the middle of a rocky landslide. |

|

| It boggles the mind that this tiny patch of land has been deemed fit for cultivation. |

|

| A girl bringing a bundle of firewood down from the valley. There were a surprising number of trees and bushes up here, which is perhaps less surprising given the lower population density near the seventh lake. |

|

| Dogs here are less wild and dangerous than in Mongolia or China, but are still very much working animals—not surprising given the Islamic view that dogs are unclean. |

|

| Gathering firewood seems to be women's work pretty much everywhere in the world. But up here almost everything is women's work. |

|

| Instead of following the road back down the valley I took one of the goat trails along the side of the mountain, staying at the same elevation or climbing slightly. |

|

| Looking back at the dam and down at Marguzor. |

|

| Views up the other side of the valley. |

|

| Looking east. Tavasang pass, leading to the next valley is somewhere up this side valley. |

|

| Looking south across this side valley. Lots of houses, connected to nearby plots of land. |

|

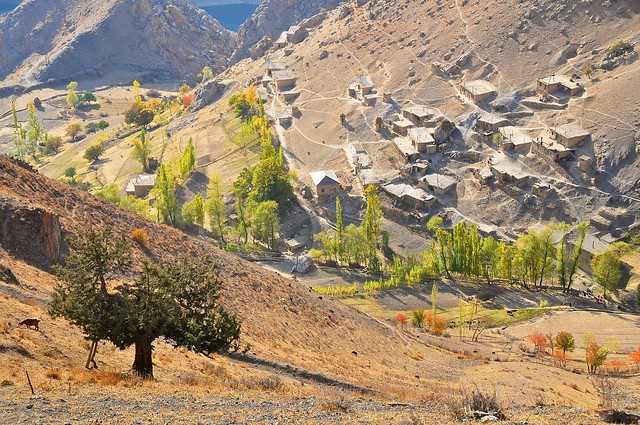

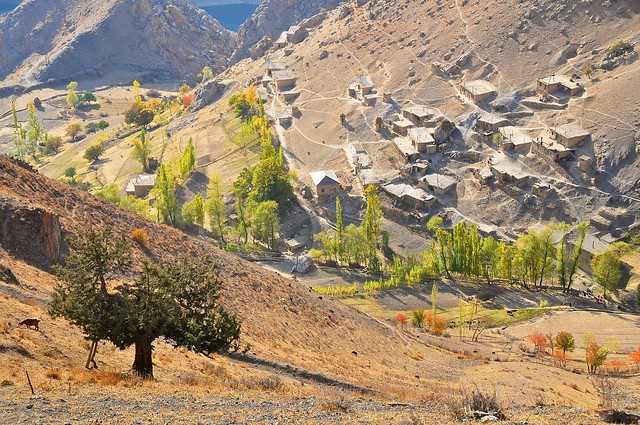

| The hillside village of Tiogli, with a few cars. It's surprising that so few of the houses have satellite dishes, especially after seeing so many gers in Mongolia with them. |

|

| A rare piece of flat land, the grass shorn by goats or sheep. |

|

| Livestock pens and shepherd huts on this little plateau. |

|

| Looking down across the valley and over Marguzor. |

|

| A shepherd's hut, and ridiculously steep fields on the other side of the valley. |

|

| Goats foraging. |

|

| This girl was looking after a few goats and agreed to pose for a picture. |

|

| So many houses! So few signs of anything to live off of! |

|

| Colourful laundry hung out to dry. |

|

| One of the last houses up the valley. |

|

| Up towards the pass. |

|

| A hawk soars above the village. |

|

| A woman looking down the valley, perhaps observing a jeep unloading its cargo from the market in Penjikent. |

|

| Channels in the ground are reminiscent of the mountainside irrigation I saw in Arslanbob. |

|

| A rare spot of flat ground at the upper end of the village. The 3300 meter Tavasang Pass should be up the valley and to the right. |

|

| Looking down at the jeep, which had attracted quite the crowd. |

|

| Parked at the end of the road, it was packed to the gills. |

|

| This was as about as close to the village as I got, for reasons to be discussed below. |

|

| A donkey waiting to be loaded up. |

|

| An old man walks up a scree-covered pathway. |

At this point, entering the village from slightly above, I was about halfway up to the top of Tavasang Pass, but I even after descending the other side it would be quite a walk to the nearest known homestay in Zimtud, and I had no decent maps.

Anyway, I wasn't really thinking of it at the moment, but was quite enjoying my walk and I started to walk through the village. Well, some local women really

didn't want me to do that, and they kept waving me away. So I retreated back

along the path and detoured above and around the village by climbing up a steep rocky slope to get above it. They

didn't like that too much, either, and made gestures from afar, but I wasn't about to abandon my walk

and retreat to the valley for nothing.

|

| Looking down at the village, after my detour up the mountain. |

|

| From this angle it almost looks like they have somewhat normal fields. |

|

| A cow in the high pasture. |

|

| Looking down at Marguzor. |

|

| The women here are incredibly conservative. Not only did they not want me to enter the village, but women working as shepherds actually ran away from me when they saw me approaching along the goat paths here as I walked along the mountain ridge! And it's not like I was close, either, as I would be about 100 meters away when they ran. |

|

| There were no large herds of animals, just a few scattered goats and a cow or two. |

|

| A goat lying in the sun. |

|

| Hay is piled in a platform around this tree, out of the reach of animals. I guess goats don't climb trees here. |

|

| Another tree platform. |

|

| Dusty buildings blend in to their surroundings. |

|

| Every scrap of land seems to support a family or ten. |

|

| Hay stacked on rooftops. |

|

| Looking down at the village. |

|

| Village houses, where the roofs are some of the only flat ground around. |

|

| This valley is completely hidden from the road, from where you would never suspect a couple hundred people would be living a couple hundred meters away. |

|

| Looking back over the ridge I came from. If I had been able to walk through the village I could have taken that road, but as it is I walked high above it. |

|

| On a ridge above this village a young girl played cat and mouse with me, moving ahead of me to stay out of sight but peeking at me every now and again. |

|

| Down at village level. |

|

| Steep switchbacks connect the village to the road around Marguzor. |

|

| On the road back to the fifth lake. |

Real hospitality in Padrud

Although it was only noon when I had reached the far end of the seventh lake and begun my trip back, after taking my time in the side valley by Marguzor, it was after 4:00 by the time I made it down the mountain to the lake-side road, and almost 5:00 by the time I was back in Padrud.

As I was walking through Padrud I was stopped by one of the guys with whom I had shared my taxi ride up from Penjikent the day before, and he asked me what I thought of the homestay, and if I was hungry (despite his lack of English and my lack of Russian, it's surprising how easily I managed to understand him). He was totally unsurprised when I said it was pretty bad, and he invited me to have tea with him.

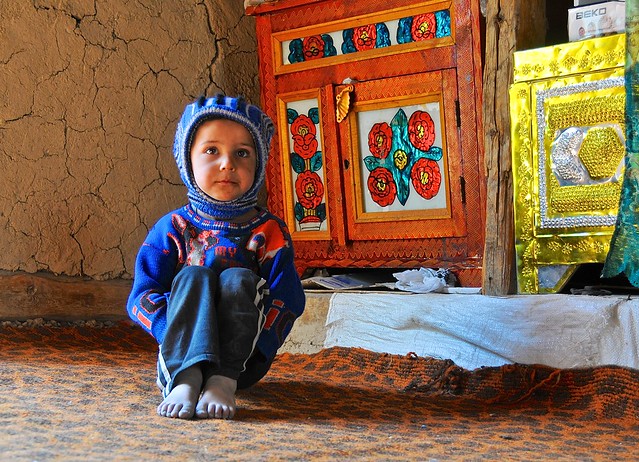

He had a tiny shop in the front of his home, and I was invited into the sleeping and living quarters, where I met his grandsons, and used my camera as an ice-breaker with them as I let them roam around with it to their hearts' content. His wife stayed in the kitchen/women's room, and his granddaughters came and went (but mainly went). Even (or especially) here it was easy to see how traditional this valley is, as I very much got the sense that it would be rather taboo for me to much contact any post-pubescent women, and the young girl who I did see a bit of was very clearly a second-class person relative to her similarly-aged brothers.

But anyway, he served me the typical snack of tea and old bread (fresh bread seems surprisingly rare in the mountains, and I didn't see the tandoors that are ubiquitous in lowland areas). This tea & bread combination is often mixed in a dish known as shir-choi, which is salty milk/buter tea with the old, stale, and hard bread mixed in—at least you don't break your teeth on the bread that way.

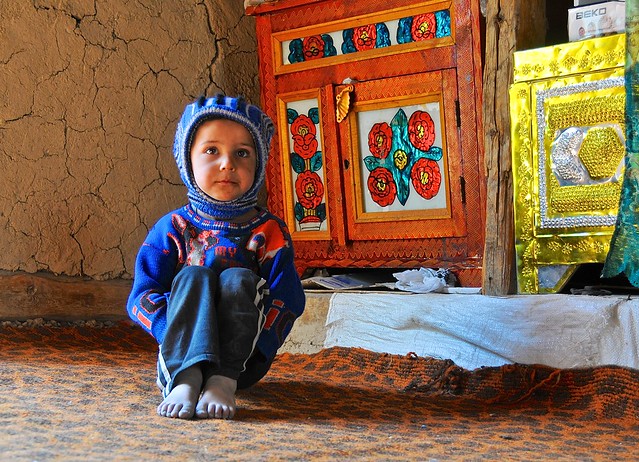

|

| Cute kid, but absolutely filthy—it's a hard life. He was the middle grandson. |

|

| Bread served on a cloth which serves as the table. And a bag in which to store the bread. |

|

| My gracious host. |

|

| One of the girls pops in for a minute, while the older brother snaps their picture. |

|

| The youngest girl was the only one who spent any time in the room. |

We talked a little, and I was able to answer a few things because 90% of conversations go the same way. The first thing people want to know is where you're from, followed by your age and whether you're married and have a family. They don't understand why someone over 25 would be unmarried and without children, and I found it difficult to understand why they would ask someone traveling solo if they were married (though the reality is that many families are forced to live apart, so being somewhere for a long time without your spouse isn't as unusual for them).

I reciprocated by asking about his family, and this was one of the first times I was able to really put a face to the statistics I had heard about. He had a large family, and was taking care of his son's children. Like up to a third of Kyrgyz and Tajik men of working age (the money these men and women send back home constituted up to

47% of Tajikistan's GDP in 2012), his son was working in construction in Moscow to send money back to his family. The problem, as he acknowledged, was that Tajikistan really had nothing but rocks and water, and there were no jobs to be had. Tajikistan's economic poverty was only amplified by Soviet policies that had encouraged large families, and even though he obviously loved his family he said he thought that two or three kids would be the ideal family size. It's such a hard life, and only harder without the centralized spending and support they enjoyed during the Soviet era.

I soon had to leave to make it down to the Nofin homestay before dark, and as I left he invited me to return the next afternoon, saying that his wife would me making plov that day (a bit strange since plov is seen as a masculine dish—the Central Asian equivalent of grilling steaks, I guess). After my experience with the Tajik guy I met in Dushanbe, I accepted his invitation and intended to keep it.

Jumaboy's homestay in Nofin: pretty darn good

I had a bit of difficulty locating Jumaboy's homestay in Nofin, given that it was twilight by the time I arrived there, and had to ask a local boy where it might be. Like the Padrud homestay, it was in a large compound, and after banging on the steel door for a while and listening to their dog bark at me, I pushed my way inside their and found Jumaboy's wife who welcomed me. And although she didn't have much time or notice to prepare dinner, the meal was far better than what I had the night before, and the service much more professional and attentive.

|

| Impromptu dinner at Jumaboy's. |

|

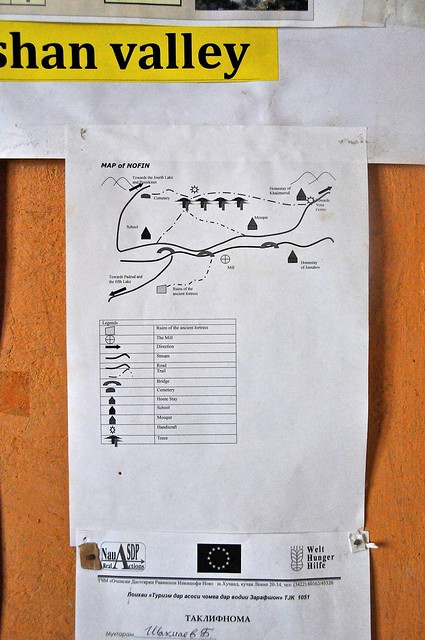

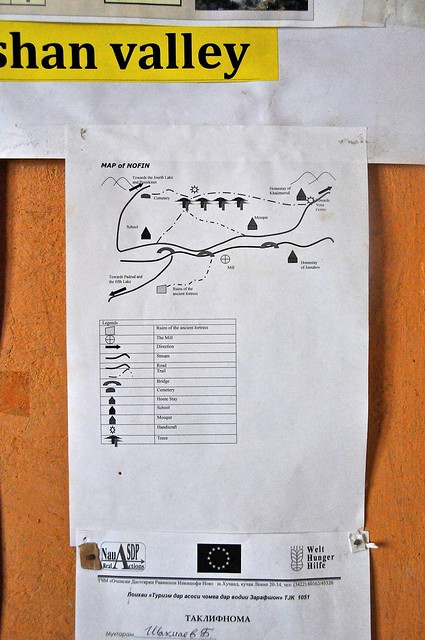

| Map of local sights in Nofin. Apparently there's the ruins of an ancient fort. |

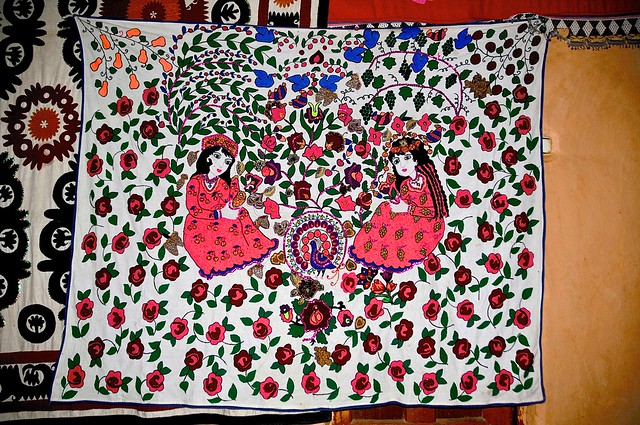

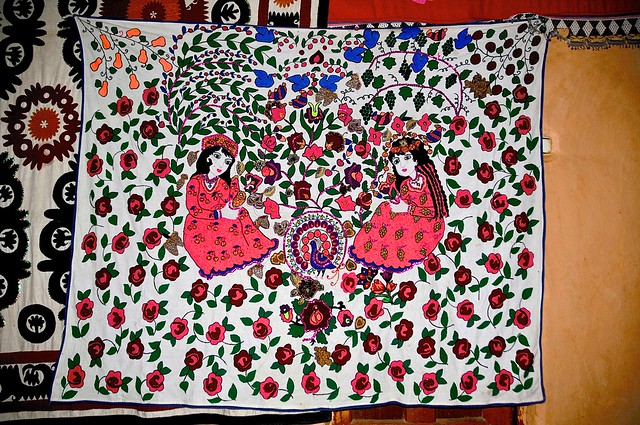

Jumaboy's homestay was pretty nice, and it was apparent that his family took it seriously. They were building some new rooms on the other side of his property, near the stream, and the rooms were decorated with the traditional

suzani needlework tapestries. While lighting the fire in the evening (the wood didn't last long, and isn't realy an eco-friendly solution, but I appreciated the gesture) the wife accidentally left behind her notebook which contained her personal Russian-English dictionary of important words and terms (along with how to pronounce them in English), which was actually pretty helpful for me in picking up a few Russian words.

I still think the ZTDA homestays are overpriced, and certainly there not something your average dirt-poor villager can participate in, but I can also see how they are useful for a small segment of the local population.

Anyway, the next morning I decided to explore the downstream section of the seven lakes, as thus far I had only seen lakes five, six, and seven.

|

| The Nofin valley joins up with the Shing valley up ahead. |

|

| You can see how high the water gets in Nofin lake, and how low it was when I was there. |

|

| Even so, one of the access roads to this cluster of houses is underwater. |

|

| Why are there houses on the side of a mountain? |

|

| It seems they always keep their donkeys saddled here. I'm not quite sure why that is. |

|

| Nofin is a deep turquoise, similar to many Rocky Mountain lakes and rivers. The colour comes from micro-fine glacial silt, ground from mountain rock-faces as glacial ice slides over it, which is then suspended in the water where it scatters light the same way atmospheric particles disperse light and make the sky blue. |

|

| It's always nice to encounter still water that cleanly reflects scenery. |

|

| The road along Nofin lake. |

|

| View of the third and second lakes, Soya and Hushyer. There are only a couple of hairpins leading down to Soya, but it's still pretty picturesque. |

|

| A flat, meadow-like area at the outlet of the third lake, Soya, with a mountain cliff-face on the other side. |

|

| Ladybugs cover the tree trunks. |

|

| They were crawling under the bark to hibernate for the winter. |

|

| The water level on this lake seems unaffected. |

|

| The elevation difference between the third and second lakes is minimal, as is the distance between them. |

|

| The Holonichiston river leading to the second lake, Hushyer. |

|

| This unusual wood and mud building, constructed on top of an animal pen, sits on the rocky dam below the second lake. |

|

| A strange little building. |

|

| Five switchbacks leading down to the first lake, Mijgon. |

|

| If you're on foot it's much faster to skip the switchbacks and walk straight down the rocky slope. |

|

| Huge boulders the size of small houses litter the slope. |

|

| View from atop one of the boulders. |

|

| Taking it all in. |

|

| The first lake has incredible colour: crystal clear, yet also deep blue. Somehow all the silt that we saw in the upper lakes has been filtered out of the water, probably when the river flowed beneath the surface between the second and first lakes. |

|

| It's pretty amazing. |

|

| Given the population density and lack of sanitation or sewage system, it's surprising the lakes bear little sign of pollution. And in general, you see little litter—certainly much less than what you would expect to see if this was in China or Mongolia. |

|

| View from the road. |

|

| The outlet from the first lake. |

|

| A tree in the rocks at the outlet of the first lake. |

|

| This lake, too, is only slightly below the high-water mark. |

|

| I needed to head back up the valley in order to make my date with the shopkeeper. |

|

| But that wasn't going to stop me from taking pictures of the switchbacks and the lake. |

|

| As you can see. |

|

| I wasn't kidding. |

|

| Along the second lake. The good thing about walking the same path in both directions is that you get to see things you probably would have missed if you didn't keep looking behind you to see where you came from. |

Tajik taarof?

In my earlier post on Dushanbe, I talked about the Iranian concept of taarof, which is a system of ritualized offers which are not to be taken literally. Like, I offer to do something for you, but only out of politeness and you are meant to decline. Although this practice reaches its apex in Iran, the extreme hospitality of Muslim and Central Asian sometimes feels like it must be like this, as it can feel like there are so many offers of hospitality that there must be an expectation that some of it will be declined. In Dushanbe I had an experience which suggested hospitality is not taarof, and that I had offended by not taking an offer as seriously as I should have, which is why I took this offer of hospitality in Padrud quite seriously.

But when I arrived at our appointed time of noon, it was clear that he wasn't actually expecting me. This led to a very brief period of uncomfortableness, but this quickly passed as I played with the kids, who were happy to see me regardless. We talked more about family and life in Tajikistan over some tea, and he surprised me by appearing with some grapes (the season was rather late for grapes, so I have no idea where he would get them). So although it was still an interesting visit, it has made me wonder about just how real taarof is in Tajikistan. Probably I was wrong to accept given how poor the family is, even if simple plov requires little more than rice and carrots, and despite his assurance that his wife would have been making it anyway.

|

| The oldest boy took the camera into the women's room/kitchen. I wouldn't have even known she existed, otherwise. |

|

| This is the oldest kid. He was full of energy and used to being the boss. I don't know if the oldest boys are like this in all families, but he was clearly treated as the most important child. He used my glasses as a costume, intentionally putting them on upside down. |

|

| The middle girl is suddenly shy. |

|

| The middle boy and I. |

|

| The three boys. |

|

| The oldest boy didn't want to share my camera with his brothers, and started doing kung-fu on them while his grandfather was out. I told him he couldn't use my camera if he was going to hit them, so they just started shadow boxing and I let the others try my camera. |

|

| Is this kid cute, or what? |

|

| The girl was so cute and so smart (she later stopped her brother from pulling the ropes in front of her face) that it's heartbreaking to know that,

simply because she's a girl, she will have even fewer opportunities and

less freedom than her brothers. |

|

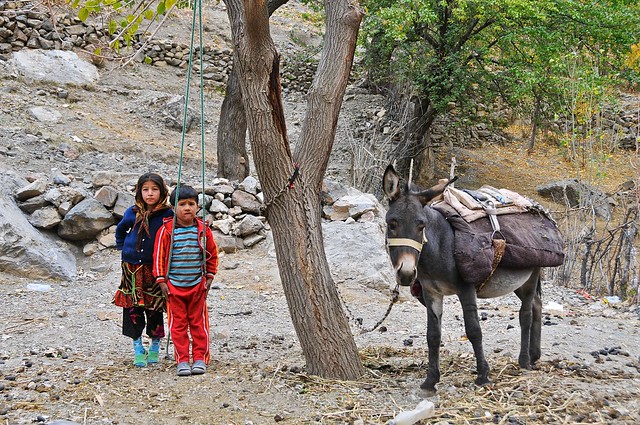

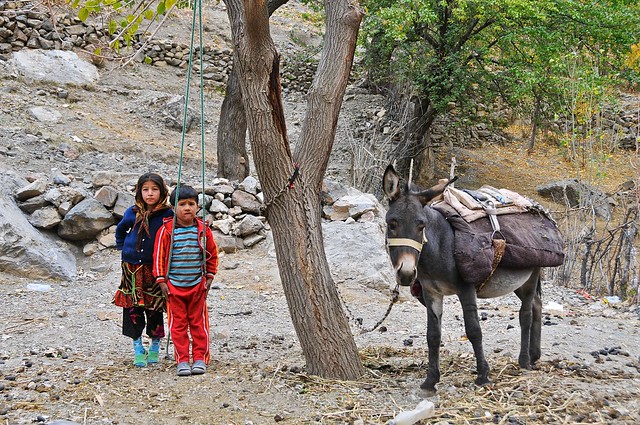

| Next to the family donkey. |

|

| Little brother joins in. |

|

| I'll be honest: I'm conflicted about this picture. I wanted to include the donkey, but only because to my western sensibilities it is more exotic to show the family and their donkey. And this feels horribly exploitative, because I'm intentionally conveying a message that the family isn't aware of and isn't how they would want to be perceived. |

|

| And here is a version cropped in camera. Well, at least both of them kind of suck. |

|

| Upper Padrud. |

|

| 360° view from the middle of Holonichiston river. |

|

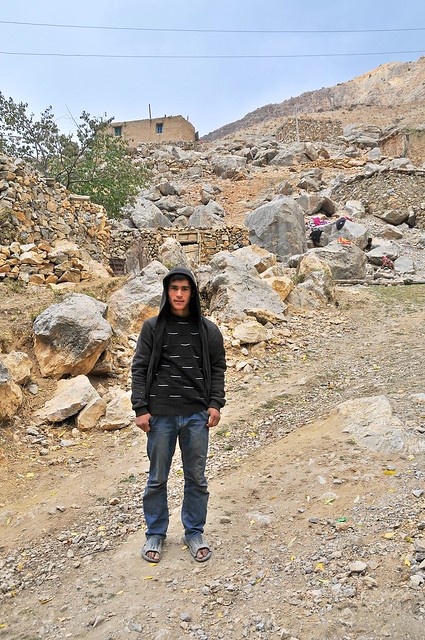

| Another local in Padrud. |

|

| As in Kyrgyzstan, you only see old men and young boys actually riding donkeys. |

|

| The Holonichiston flows into the fifth lake. |

|

| Looking down over the fifth lake to one of the uppermost houses in Padrud. |

|

| Two little calves by the side of the fifth lake. |

|

| Passing by the shopkeeper one last time on my way back to Nofin. I didn't want to insult his hospitality, so instead I bought a bunch of snacks from him and gave the kids some of my chocolate (and made sure they shared with the girl). I probably should have figured out a way to give him some money, but it would have been difficult to do without insulting him, In retrospect, giving him money and asking him to buy something for the kids would have been a good solution. |

|

| A panorama from the southern side of Nofin valley, near the cemetery. |

|

| Around to the northern side, looking down to the main Shing valley. |

|

| Looking down at Nofin lake from up behind Jumaboy's, with the fort ruins down the hill to the left. |

|

| Looking up the Nofin valley. |

|

| Ruins of the old fort in the foreground, with Nofin lake below. The ruins are about as well defined as most of the ancient city in Penjikent. |

|

| Jumaboy's homestay. The homestay rooms are in the middle of the picture, above the ocher stripe. The room with lots of windows is where I ate, and the sleeping room was next to it. |

|

| He was building what appear to be more private lodging when I was there. The stream running down the Nofin valley is right behind them, and the entrance gate is to the left. |

|

| Outside water basin with whimsical decoration. |

|

| Homestay room. Western-style beds are an unusual feature for the region. The walls are decorated with suzani. |

|

| Most homestays just use the kurpachas you can see stacked on the wall. |

|

| Dinner on the second night. |

|

| Perhaps the only thing I didn't like was the sales show Jumaboy puts on during your final night. He brings out carpets and suzani and gives a little sales pitch. I think the pricing is pretty fair (the suzani pictured was listed at 480 somoni, or about $105, while a kelim carpet was 530 somoni) and a lot of people might appreciate the opportunity, but it feels a little bit of a hard sell to me, like resorts that offer deeply discounted or free accommodation so long as you listen to their time-share pitch... except you get no discount here. |

Budget

October 18, 2012, Penjikent to Nofin: 110 somoni

- Coke (5) and 2 samsas (8): 13 somoni

- Share taxi to Nofin: 25 somoni

- Room at Nofin ($10): 48 somoni

- Dinner ($5): 24 somoni

October 19, Padrud: 90 somoni

- Breakfast ($2): 10 somoni

- Wafers, soups: 8 somoni

- Room at Jumaboy's homestay: 48 somoni

- Dinner: 24 somoni

October 20, Padrud: 82 somoni

- Breakfast ($2): 10 somoni

- Room at Jumaboy's homestay: 48 somoni

- Dinner: 24 somoni

job site

ReplyDeleteGreat post! I’ve been on the job hunt recently, and a lot of the advice you shared resonates with what I’ve been learning. One platform I’ve found useful for posting job openings is freepostjobs.com. It’s a great resource for employers looking to post job listings without any fees, and I’ve seen many success stories from both job seekers and employers alike. If anyone’s interested in learning more about posting or searching for jobs, I’d highly recommend checking it out! Keep up the great work with your posts! jobs in durban