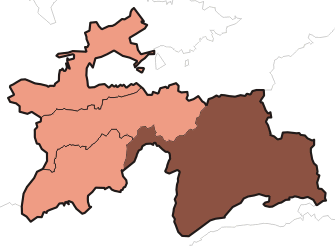

GBAO: the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast

Basically all of the Pamirs and the entire southeastern knob of Tajikistan falls within the administrative region known as Gorno-Badakhshan. And if ever there was a part of the country that could be said to contain nothing but rocks and water, it would be the GBAO, which occupies 45% of Tajikistan but has only 220,000 people (about 3% of the population).

Pamiris are Ismaili Shias, while most Tajiks are Sunni

The region is not only geographically distinct, but ethnically and religiously as well. The northeastern part of the GBAO, along the Pamir Highway from the Kyrgyz border until at least Murghab, is mainly Kyrgyz, while the western GBAO and areas near Afghanistan (which are significantly lower, though still above 2,000 meters) are mainly Pamiri. Pamiris have their own languages, but like Dari and Tajik, these languages are minor variants of Farsi and seem to be mutually intelligible for the most part. The main point of distinction between Pamiris and the Tajik is religious: while lowland Tajiks are Sunni, like 90% of Muslims in the world, Pamiris are Shia—and more specifically, Ismaili (which are only 20% of Shias).

Attending university in Calgary, I knew quite a few Ismailis: we had a sizeable population of Gujarati Ismailis who worked as traders and settled in East Africa, but were then

expelled from countries like Uganda after they gained independence (Indian merchants being convenient scapegoats). Many seem to have

somehow made their way to Calgary. Indeed, the beloved mayor of Calgary,

Naheed Nenshi, is an Ismaili Muslim of Tanzanian extraction.

So who are the Ismaili's? Well, here's an excerpt from a great piece on Ismaili Islam on Paul's Travel Blog:

The Tajik Pamirs and northern Pakistan share not only mountainous

terrain and certain ethnic/cultural links but also religion: Ismaili

Islam. The Ismailis are Shiite Muslims who believe that the true

seventh Imam was a man named Ismail rather than his younger brother

Musa, as the Twelver Shiites (such as those of Iran) believe. While

during certain periods, such as the Cairo-based Fatimid Empire, Ismailis

were a powerful force, today they form a small minority of Muslims,

often scattered in remote mountainous terrain.

The historical distinction between Ismailis and other Shiites may

seem minor, but, over time, this simple succession dispute has led to a

universe of divergence, as Ismailis have become among the most

progressive of the Islamic sects, in stark contrast to the Shiites of

Iran. Indeed, the distinction between Ismailis and other Muslims has

grown so great that one (Sunni) Kyrgyz woman in Tajikistan told us that

the Tajik Pamiris were not even Muslim. Of course, despite the strong

lingering of pre-Islamic beliefs and traditions the Ismaili Pamiris are

in fact Muslim, as are the Ismaili Hunzas of northern Pakistan, but it

is true that the Ismaili worldview of the twentieth and twenty-first

centuries is clearly a world apart from some other sects of Islam, and,

to this outsider, far more appealing.

Ismailis are also different from most other Muslims in that they have the Aga Khan as a living spiritual advisor, whom they see as a direct descendant of the seventh Imam, and more importantly they believe that he is able to interpret the Quran in the modern context. I suppose this might make him something like the Pope, but the Aga Khan is quite different than the Pope in that he is an extremely modern man (in this he more resembles the Dalai Lama), was born in Switzerland, and is something of a playboy. Imagine Tony Stark as the leader of a branch of Islam and you're not too far off. I mean, his parents were divorced and his father then married Rita Hayworth, which tells you a lot about his family and their values—especially given that his grandfather was the prior Aga Khan and passed on his duties to his grandson because he wanted even more modernity from the future leader.

The net effect of having a branch of Islam being led by this Swiss-born spiritual leader is that Ismailis are hugely progressive by the standards of just about any religion, and the hugely wealthy Aga Khan remains close to his followers and spend hundreds of millions of dollars per year through his Aga Khan Foundation and Aga Khan Development Network to advance the development of his people and their surrounding communities.

The impact of the Aga Khan and the magnitude of his contributions are most apparent in the GBAO—and in Khorog in particular—as so many of the things that make the town so special have been funded by the Aga Khan. From quite literally building bridges that connect communities and countries, to providing food aid during the civil war, to spending in the medical community, to providing education, to hearing people in the streets tell you that they do things (or don't do things, like drugs) because of the guidance of the Aga Khan. One area where you see a real difference is in how women are treated. Unlike in the ultra-conservative Fann Mountains, women play a real role in civil society and assume positions of leadership within families. Girls are not second-class citizens, women don't run away from even the most fleeting contact with men, and there seems to be no thought of denying them education because of their sex. It's no coincidence that the homestay I stayed at is known as Lalmo's homestay, and not Lalmo's husband's homestay: women are empowered to a startling degree.

The post-Independence Civil War

Now, in the paragraph above, I alluded to

the civil war. Tajikistan is the only one of the Central Asian CIS countries that devolved into civil war following independence from the crumbling Soviet Union, and given the cultural and logistical differences between the GBAO and the rest of the country perhaps it's no surprise that Badakhshanis and the lowland Tajiks were on opposing sides... or that the lowlanders won.

The current President, Emomali Rahmon, came to power as a result of the civil war, and he has basically been the only leader that an independent Tajikistan has ever known. In the wake of the civil war it seems that Rahmon granted government positions to a number of warlords and opposition leaders in a attempt to placate them and ensure a measure of government support—something that was probably of special interest given the strategic importance of the GBAO given its long borders with China and especially Afghanistan.

Despite these concessions, there has been a long history of tensions between the Pamiris and lowland Tajiks. Part of this tensions is religious (many Tajiks think that Ismaili Islam isn't a pure or legitimate form of Islam, epsecially since it views the Quran as open to interpretation by the Aga Khan) and part of it is a resentment by the Pamiris that the government treats them unfavourably (you certainly hear people saying that there were better services during the Soviet era, and although you hear this in lots of former second-world countries, in the Pamirs I think there is the suspicion that the decline has been due to them being Pamiris and not lowland Tajiks). Virtually everyone in the GBAO will self-identify primarily as something other than Tajik, be it Kyrgyz or Pamiri.

First impressions: walking from the Airport to Lalmo's

I don't know what I was expecting from Khorog. Something high and harsh, maybe. Small and rough. And definitely running north-south along the border with Afghanistan. On pretty much all fronts I was surprised. Although Khorog is at an elevation of over 2,100 meters, the town is surprisingly green and full of trees. And for late October, it was a lot warmer than I expected, and pleasant to walk around in the sun. Heck, this would be better weather than one would expect in Calgary, and the climate also supports a greater range of trees. Looking at weather profiles for Khorog, however, it seems like a remarkably temperate city, with the average high in October of 18°C (65°F)—only in January is the average high below freezing.

And despite the harrowing road journey from Dushanbe, Khorog didn't feel as isolated as I expected. The markets were well stocked—certainly much more so than I saw in Kyrgyz Alay Valley communities like Sary Mogul, Sary Tash, and Daroot Korgon. Maybe this shouldn't be so surprising, as it actually lies on the closest road to China, which would run through the Pamir border of Qolma before running through Murghab and Khorog on the way to Dushanbe.

Among the ubiquitous Chinese goods at the market there were some distinctly Pamiri items like huge and bulky socks and knitted toques ("knit cap" in American). Perhaps the only way the town revealed its isolation was in the food situation, as there didn't seem to be many restaurants.

|

| An old Soviet-era social-realism style painting on a pole. |

|

| The "Hitler" look is apparently respectable in Tajikistan. Or maybe it demands respect. Or fear. Or something. Based on some things I later saw in Murghab, this guy appears to be some sort of government official. |

|

| Khorog lies along the northern and southern slopes of the Gunt River, just before it joins the north-south flowing Pyanj river, which forms the border with Afghanistan.The Gunt almost seems bigger than the Pyanj. |

|

| Lalmo's homestay. When I was there she was putting a roof on her house. |

Lalmo's is on the northern side of town, up a hill, across from the popular

Pamir Lodge. To get to the entrance you have to go onto the grounds of

the school next to it, and then take the stairs up from the playground. I met Lalmo and dropped off my bag, agreeing (given the paucity of food options in town) to have dinner that evening at Lalmo's, and then headed back down to town to explore.

|

| A grove of trees just west of Lalmo's, in resplendent fall colours and draped with laundry and bedding being aired out. |

|

| Looking northeast from the local cemetery, which is high over the river. |

|

| Stones on the north face of the mountains spell out a message of welcome for the Aga Khan. |

|

| West along the Gunt. |

|

| Fresh graves from the recent unrest. Piola cups are turned over and smashed over a stone on the grave. |

|

| Just a dusty road on the north side of the river. |

|

| Lenin surveys the town. |

|

| New houses being built in the traditional method: with thick stone walls, which will be covered by plaster and ultimately look like Lalmo's. Even though these houses rely mainly on freely-available stone, they are becoming less common because of the sheer number of stones required for such thick walls and the expense of hauling them from the countryside. |

|

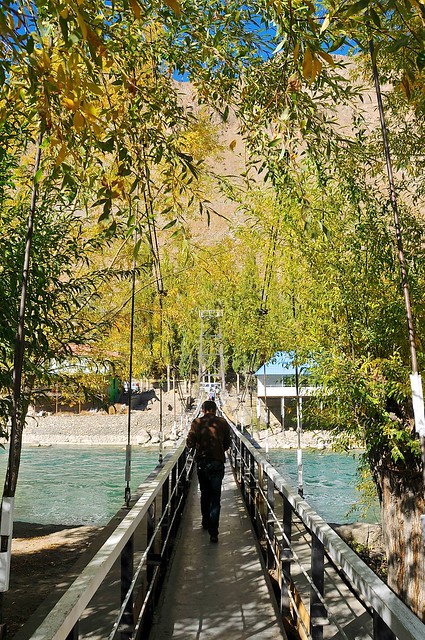

| Pedestrian bridge leading to the market that sprawls along the river. The taxi lot for the Wakhan valley is on the south side of this bridge, where I'm coming from. |

|

| Near the middle of the bridge. |

|

| Looking east up the Gunt. |

|

| And west towards the Pyanj. Those mountains ahead are in Afghanistan. |

|

| The north side of town. I bet in the depths of winter the north side sees barely any sunlight. |

|

| There are lots of stray dogs in Khorog, which is something you don't see pretty much anywhere else. Despite being stray they are friendly and approachable, no doubt because the Pamiris will fed them and be nice to them. I bought some fried foods at the market (hot dogs, eggs, and doughy things are popular) to give to some dogs. |

|

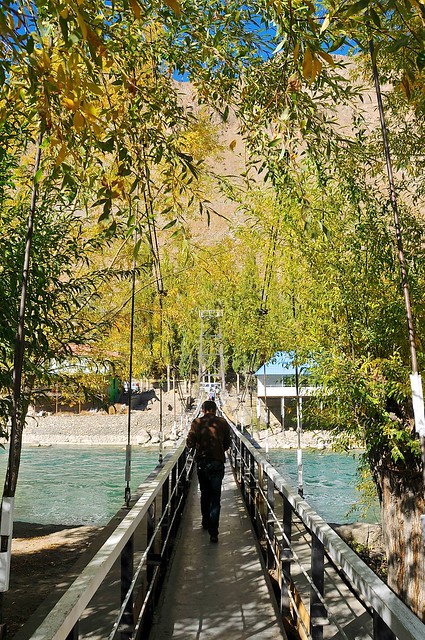

| Another pedestrian bridge near the north-side covered market and the shops around it (which is also where the parking lot for cars to Murghab leave from). |

|

| Looking east. Khorog's Central Park is straight ahead on the left bank. |

|

| Another view of the welcome message for the Aga Khan. |

|

| Trees in Central Park. I don't know why, but there's something very special about the combination of closely spaced trees on a green lawn, with deep shadows from light streaming through their trunks. |

Down in Central Park are a few souvenir shops and tourist information agencies. These operations all seem to be supported or founded with the assistance of international NGOs, and the people in the tourist offices were knowledgeable and friendly. When they heard that I wanted to possibly visit the Afghan Wakhan, they warned me that the borders would be probably be closed for the Muslim holiday of

Eid al-Adha, which commemorates the willingness of Ibrahim/Abraham to sacrifice his first-born son to Allah, and that the Saturday market in Ishkashim would also be closed for this reason. This was disappointing, but good to know.

More surprisingly—but perhaps not that surprising given how few tourists were in town as a result of the GBAO only recently being re-opened—they seemed to know pretty much all the tourists in town, as they told me that there was a Swiss lady in town who was also going to the Wakhan. They didn't know where she was staying, but they said she would also likely be going there soon.

|

| Apparently during the civil war food was in such short supply that Central Park was plowed up and food planted there. The Aga Khan provided food aid during the worst of the famine and has helped reconstruct the town as well as tons of money for the region afterwards. |

|

| The moon rises over the mountains to the south. |

|

| In the summer this is full of water and acts as a swimming pool. I wonder if any women use it: in the Fann Mountains it would be unimaginable, but seems realistic in the Pamirs. |

|

| Thanks to the efforts of the Aga Khan Foundation and other NGOs, Khorog feels like the most well-educated spot in Central Asia outside of maybe Almaty and Astana, and certainly with the highest level of English speakers, making the appearance of this sort of English-language slogan less surprising. |

|

| The hills north of town in the afternoon light. |

Back at Lalmo's I found she had laid out the bedding for the night, and I was happy to discover that her house had both a western-style flush toilet in its own little room next to the entrance as well as a good shower in the adjacent laundry room. In retrospect it's surprising how new her house and its facilities felt (when traveling on a budget you either get facilities that either actually date from the Soviet era or which feel like they do), which gave her homestay a curious feeling of being both new and traditional... which is actually very much in keeping with the progressiveness and traditional culture that characterizes Khorog.

|

| Dinner at Lalmo's. I might have been disappointed that it wasn't traditional Pamiri food if the roast chicken and french fries weren't so good. Given the general lack of restaurants in town and how expensive they are, $5 for this spread is actually pretty good value. |

|

| Breakfast the next morning. |

|

| My kurpacha in the guest room, with the morning sun streaming in. Her kurpachas even had sheets that were very similar to Japanese futon sheets, with an open area on the back. |

|

| What I assumed to be local dormitory accommodation for students. |

Before heading to the taxi lot for Ishkashim and the Wakhan I stopped by the Afghan consulate to see about getting a visa. The folks at the consulate were friendly and helpful, and also warned me that the borders would probably be closed between Thursday and Monday. Given that my Tajik visa was running out, and would expire on the 30th, I knew that even under the best of circumstances I wuold only be able to visit Afghanistan for two or three days at most, but I decided to get a visa just in case it turned out to be possible to make a visit, however brief (and I'll also admit to doing so in part out of a vain desire to collect another visa and another country). But whereas I had been told in Pingyao that an Afgahn visa could be obtained in a couple of hours for $35, and that the fee should be paid at a bank in downtown Khorog, the consulate officials were asking for a $50 visa fee plus a $50 urgent-processing fee, all to be paid to them in cash. This kind of situation reeks of graft, and it's pretty clear that they would be pocketing the lions share of what they were asking for. I told them I couldn't pay that much, and they quickly cut their price to $50 plus a $20 processing fee. This was acceptable to me, not least because it was the price quoted to me in Dushanbe for three-day processing, so I coughed up $70 and got my visa in minutes. And all without even entering the consulate grounds, as they simply cracked open a window in the metal gate to their compound courtyard, and talked to me through that.

On to Ishkashim and the Wakhan!

|

| I lose towels all the time, and often just use a dirty T-shirt as a towel since I'm somehow less likely to leave those behind. In the market I saw this towel and had to get it, even if it is huge (it was also really thin, so it didn't take up that much space or weight). I still wonder what a Pillsbury Dough Boy beach towel was doing in Khorog. |

|

| The bridge to the covered market area. |

Budget

October 23, from Dushanbe to Khorog: 536 somoni

- Flight from Dushanbe: 440 somoni + 10 somoni in overweight charges

- Assorted fried items a the market: 8 somoni

- Apples: 5 somoni

- Internet: 1 somoni

- Room: 48 somoni ($10)

- Dinner: 24 somoni ($5)

No comments:

Post a Comment