In the morning we had breakfast and then settled up for our room and board. Aydar asked 50 somoni but was open to negotiation. Meggy thought this was a bit much, but given that official homestays cost that much for a bed and breakfast alone, I thought his price was quite fair, especially given that we each had our own room and there was a western toilet... and especially since it had been a rough year for tourism with the region closed for tourists for most of the peak season.

We ended up paying 50, and Aydar helped us find a ride into Ishkashim. There's a fort near Ishkashim, on a hill between the road and the Pyanj river, which many tourists stop at and which is somewhat known for being frequently occupied by Tajik border guards who don't take kindly to unannounced visitors, but since we weren't in a private car we didn't stop. Most of the excitement involved in stopping at this fort seems to center on interacting with the border guards, anyway, so I don't think it was any big loss.

Once we alighted in Ishkashim we first headed west of town to the location of the cross-border Saturday market to confirm it wasn't being held, then came back into town and explored the regular, daily market. The market was pretty basic, but we picked up some fruit and snacks. Ishkashim seemed like a pretty basic town, and in 2012 there were somewhat surprisingly no real places to stay there, even though it was the jumping-off place for exploring the Afghan Wakhan. And even though not a lot of tourists explore the Afghan side, there are plenty of traders and local who do cross over into Afghanistan (or vice-versa), so the lack of options is somewhat surprising.

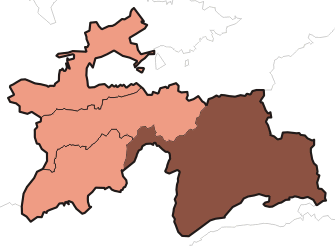

|

| Cool bus stop. Does this mean they had proper bus services in the Soviet era? |

|

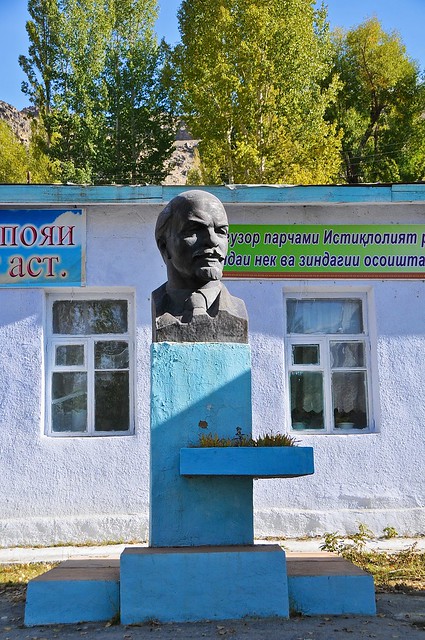

| More Lenin, with some of Rahmon's words of wisdom on the walls behind. |

|

| Interesting construction techniques: concrete supports on the lower level, stone walls, and rough wooden logs as floor and ceiling supports. |

|

| Building new shops in Ishkashim's market area. |

Strange happenings on the ride from Ishkashim to Khorog

We managed to find a car heading back to Khorog without too much difficulty. All of the other people in the SUV were young guys in their twenties, and out bags were stuffed in the back.

As we left town, we made a brief stop at a farmhouse just outside Ishkashim. These kinds of stops to pick up passengers and cargo are pretty normal, but this was a bit different, as we stopped about 100 meters from the house and they didn't want us to get out. The driver and his friend headed inside, then a couple of minutes later they came running back to the car, jumped in, and we immediately sped out of there. This is all very strange, as you never see anyone running, and usually no one is in a rush to get into a car (even if the driving is often quite manic). The concern was amplified when one of the guys in the rear seat started stuffing things into someone's bag—we couldn't see what he had r where he was putting it, but something was going on.

Meggy and I exchanged slightly concerned glances, and we were both a little apprehensive when we reached the checkpoint between Ishkashim and Khorog, as we were both thinking that possibly these guys had picked up (or stolen) some drugs or other contraband and put them in our bags to help smuggle them through security. It turned out we had no problems at the checkpoint and there was certainly nothing removed from our bags before we left, so while the circumstances around that little stop remained a mystery, it was likely much more innocuous than we imagined. Or maybe not.

Anyway, during the post-checkpoint ride to Khorog, we talked a bit with some of the guys, and it turns out that a couple of them were Afghanis from Afghanistan's Ishkashim who were studying and living in Khorog. I was a little surprised to hear this, as I kind of figured that Tajikistan would make things difficult for foreigners (from poorer countries) who wanted to live and study in Tajikistan, but apparently it isn't that uncommon in the region.

Back in Khorog

In Khorog we were dropped off at the taxi lot, and then decided to head over to the botanical gardens for the afternoon. Meggy was going to stay with the family she had stayed with the last time she was in Khorog (she had met a woman on her car ride from Dushanbe, and the woman had invited her to stay with her), so she went there while I headed back to Lalmo's. We met a half hour later, and took a marshrutka to the botanical garden, which is on the east side of town on a bluff south of the river overlooking the town.

I'm not quite sure what your typical botanical garden looks like, and October probably isn't prime viewing season, but this garden seemed to be mostly trees, with a path winding through it and a few picnic areas. On the south edge of the garden, overlooking the valley below, there is a large and impressive European-style house (currently undergoing renovation)—this building doesn't really have anything to do with the garden, but is one of the President's residences.

Behind the President's house is an orchard full of regularly planted apple trees, which were full of fruit when we were there. There was some fruit on the ground, and many apples which could easily be knocked loose by shaking the tree or throwing sticks up at branches.

After filling our pockets with apples, we returned to the President's house and headed down the grassy slope to the valley below, where we had spotted an interesting building near the river. It turned out to be a fancy chaikhana that was surrounded by a chain-link fence and locked up. I think it was used mainly during big events like Presidential visits and weddings. The guard came out to the entrance gate and after chatting with Meggy he let us in and gave us a brief tour of the exterior. It was impressive overkill: the sort of ostentatious but useless buildings you see being built in Dushanbe by people like Rahmon, and not the sort of functional infrastructure built in the Pamirs by the Aga Khan.

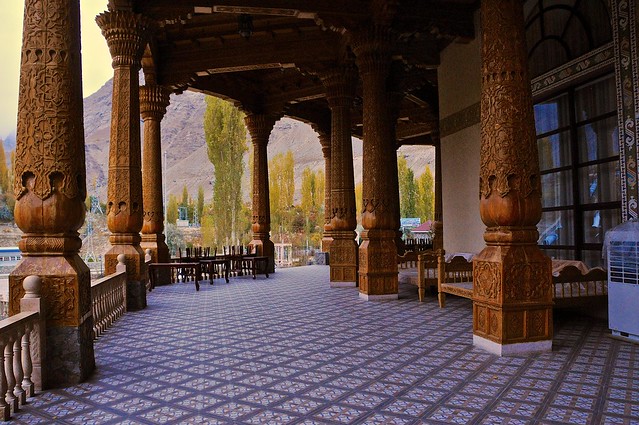

|

| The ornate and little-used chaikhana. |

The weather in Khorog was disappointingly grey and cool, which only served to remind us how lucky we had been with the brilliantly sunny and warm weather we had enjoyed for the last few days. When I got back to Lalmo's she said that she had forgot to ask me if I wanted to eat there that evening, and when I said I did (it was dark and I didn't want to head down into town to find the Delhi Darbar Indian restaurant, which is pretty much the default option for travelers in Khorog) she was kind of pressured to whip something up on short notice. Reminder: always let her know in advance if you want dinner, as if she has notice she can make pretty great stuff.

Speaking of food, while walking to Lalmo's, I had encountered a young boy who offered me some food. I declined, and in doing so I think I committed a serious faux pas. As I said earlier, the Afghan market and the borders with Afghanistan were closed at this time for Eid al-Adha, which commemorates the willingness of Ibrahim/Abraham to sacrifice his son for God/Allah. Today, Muslims who can afford to do so commemorate Ibrahim's sacrifice by sacrificing their best animal, which they then divide into three portions for themselves, their neighbours, and the needy—and that distribution of food is what the boy was doing when I turned him down. This sort of community spirit is something I love about Islam: their religious holidays are still very much about the community and the less fortunate, and taking care of them. Ramadan is all about depriving yourself of food so you can understand how the hungry feel every day, and breaking the fast is about inviting the community to share in your food. Now think of the largest Christian holidays and what they mean (or don't). It's because I found the philosophy behind Ramadan so appealing that I started to observe Ramadan in my early twenties: it's a holiday that makes sense, unlike my equally secular historical observation of Christmas.

Speaking of food, while walking to Lalmo's, I had encountered a young boy who offered me some food. I declined, and in doing so I think I committed a serious faux pas. As I said earlier, the Afghan market and the borders with Afghanistan were closed at this time for Eid al-Adha, which commemorates the willingness of Ibrahim/Abraham to sacrifice his son for God/Allah. Today, Muslims who can afford to do so commemorate Ibrahim's sacrifice by sacrificing their best animal, which they then divide into three portions for themselves, their neighbours, and the needy—and that distribution of food is what the boy was doing when I turned him down. This sort of community spirit is something I love about Islam: their religious holidays are still very much about the community and the less fortunate, and taking care of them. Ramadan is all about depriving yourself of food so you can understand how the hungry feel every day, and breaking the fast is about inviting the community to share in your food. Now think of the largest Christian holidays and what they mean (or don't). It's because I found the philosophy behind Ramadan so appealing that I started to observe Ramadan in my early twenties: it's a holiday that makes sense, unlike my equally secular historical observation of Christmas.

Budget

October 27, from Yamg to Khorog: 157 somoni

- Taxi from Yamg to Ishkashim: 25 somoni

- Taxi from Ishkashim to Khorog: 60 somoni

- Room and dinner at Lalmo's: 72 somoni ($15)