The Marshrutka to Arslanbob drops you off in the town square, which is essentially a big gravel parking lot with a small statue in the middle. A short walk uphill along the river from the square is the CBT office, which should be your first stop.

CBT, or

Community Based Tourism, is a Kyrgyzstan-wide tourist initiative that helps connect tourists with local homestays and tour guides. The basic idea is that the central CBT offices help train the homestay and service providers, while certifying their offerings (homestays are classified according to the amenities they offer) and providing centralized booking services. In return, they receive a commission of about 15%, with the remainder going to the local operators.

CBT was launched in 2000 by the Swiss NGO

Helvetas, and my understanding is that they provided significant start-up funds, training, and infrastructure support. Unfortunately, CBT seems to have gone through some growing pains when Helvetas withdrew and turned over all operation to local Kygyzstanis. Some of the more popular homestays disliked paying a commission to the local CBT office, and withdrew. Some of the CBT booking offices started directing most or all tourists to favored homestays they might have connections with, meaning that only a select few providers actually benefited from the scheme. CBT offices throughout the country continue to offer varying levels of assistance, expertise, and availability, making it difficult to evaluate the CBT as a whole.

The CBT office in Arslanbob seems to be one of the best-run offices in the entire country, even if it does seem to support an unsustainably high number of homestays, at 18. They seem to provide fairly impartial allocation and travel advice/information, even trying to develop skiing in the area. They can also provide internet access through a cell-phone based modem, but this is pretty pricey.

Anyway, I opted for an English-speaking host, and homestay #13 was suggested to me. This was located a kilometer or so west of the square, near the access road leading up to the plateau that sits to the southwest of the village. The homestay was really quite nice, with all of the guest rooms located in a separate building with about three bedrooms and a common room that could collectively sleep about a dozen people. The houses feel quite Russian, with stucco walls, pastel colours, and lots of lace and floral prints.

As with most places outside of the major cities, there is no real plumbing and no sewer, which means long-drop outhouses. In practice, this typically entails a separate outbuilding with a cement floor with a narrow slot in it: a squat toilet. Even though it's an outhouse, you don't throw your used toilet paper down the hole, but in a bin next to the toilet (outside of Japan, it has been the norm to put used paper—which you've

typically supplied yourself—in a bin and not down the toilet). Depending on how well the toilet and pit has been maintained, it might not even be that unpleasant an experience.

Even places with long-drop toilets typically have hot showers, as it really doesn't require much more than a hot water heater and gravity. They'll be placed in another area, sometimes even in places with dirt floors, and while gravity alone doesn't lead to very good water pressure, they get the job done... just be sure to wear your flip-flops.

The host of our homestay was a schoolteacher who had been mayor of the village in the past (one of his prouder achievements as mayor was to eliminate hard alcohol from Arslanbob), and he—like over 90% of the village—was Uzbek. It's a little surprising to find so many Uzbek (the population of Arslanbob seems to be almost 10,000) in the mountains, but there is a surprising amount of farming in the village. Like most Uzbek families, this one was large, as I believe he had something like seven children, and would have been happy with 10 (it's a nice round number, and why wouldn't you want 10?).

|

| This stream runs in front of the homestay I stayed at. Even at the end of summer there was still abundant water flow from high-elevation snows and glaciers, and these streams (which run everywhere) are the source of water in Arslanbob, which otherwise has no central plumbing system and certainly no sewer: this was one of the only pipes I saw, as most water was sourced directly from streams. |

|

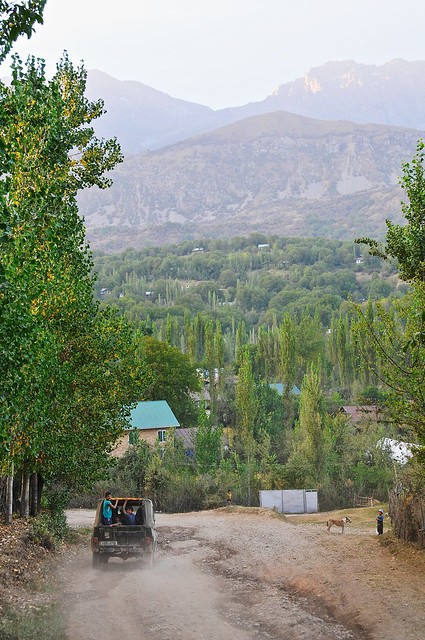

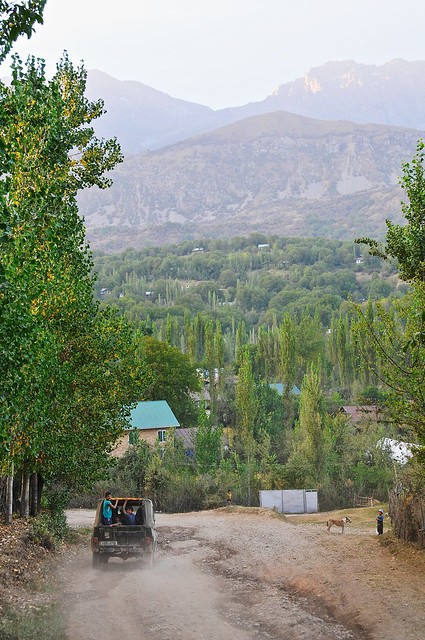

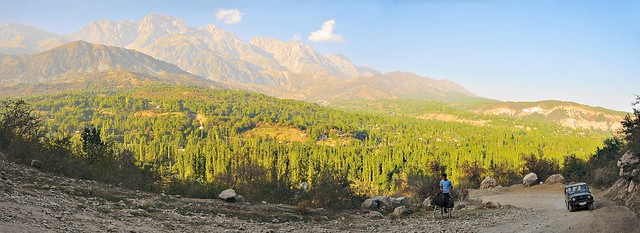

| Looking down the road up to the plateau. Everyone was coming down from a day working the fields up there, by ancient jeep, truck, donkey, and foot. |

|

| Apparently kids in Kyrgyzstan pose like soldiers at attention. |

|

| At ease. |

|

| Donkeys are a common form of transport, mainly for young kids and old men. |

Maike the volunteer cheesemaker, NGOs, and a culture of dependency

On my first night in Arslanbob I met the only other person staying at my homestay. It turned out to be a Swiss girl named Maike, who had actually been in Arslanbob all summer to help

teach the locals how to make cheese, on the theory that the locals could make a lot more money selling cheese than they could selling kefir or

kurut (dried yoghurt balls, which sound quite appealing but are really super-salty balls of disgusting).

It turns out that chessemakers work long hours and, even in Switzerland, don't get paid very much. For Maike, it was a real sacrifice to take three months off work and pay her way to Kyrgyzstan to volunteer there. I figured that—even aside from the dependency problems I've seen with NGOs before—a Swiss worker was likely to encounter some culture shock when it comes to Central Asian workers, so I asked her if she had had any problems. Unsurprisingly, she had.

Before deciding to come to Kyrgyzstan, Maike had tried to do he due diligence to make sure it was worth it, and to make sure she would be able to have a positive effect, making sure that she would have willing students and enough milk. She asked how many liters of milk per day she would have access to: 100, 1000, or how much (it apparently takes about 10 liters of milk for one kilogram of cheese)? She was assured she would have as much milk as she wanted. Of course, this turned out not to be true, and her milk supply was severly constricted for two main reasons: one, most of the cows were in high pastures, making milk in the valley fairly scarce; and two, the locals have such a culture of kefir that they were loathe to divert milk to cheese making.

This would be discouraging enough on its own, but the difference in punctuality and work ethic was another chock to her system. In Switzerland, she was accustomed to getting up around five and working until late, so she figured that asking for a 9:00 start would be more than generous. But to her disappointment the girls would show up at fairly random times, and sometimes those girls assigned to bring milk would show up empty-handed, and without an apology or excuse.

After adjusting and discussing her frustration with other NGO workers in Bishkek, I think she came to terms with what she was doing and accepted that she was having a positive impact, even if it wasn't as she had imagined: some of the girls really were quite good at the cheese-making, and she had actually taught them the skills she wanted to, even if it was unclear whether they would turn their skills into a sustainable money-generating business.

It turned out that my first day there was also her last, and that in honor of her last day there the CBT office was giving her a small ceremony at dinner. It was nice, but it was also sad. Although they thanked her and although their appreciation was no doubt sincere, there was also no sense that Maike had actually made any sacrifice or that this was anything other than a big, long vacation for her. At one point the host said that she should come again next summer, and that they would probably have more milk for her next time. And this, I think, is part of the problem with NGOs and their endless supply f money and projects (though tourists like myself probably contribute as well): it creates the expectation and belief that there are foreigners who have too much time and money and nothing better to do with it than spend it on projects in developing countries. Instead of looking at these projects as opportunities, there's an understandable tendency in aid-rich countries to see them as entitlements or foreign-led initiatives that the locals have little vested interest in. Obviously the way these projects are designed and led has much to do with this, as it is true that many NGO projects are designed with little attention to the actual needs or desires of the local communities they pretend to serve, and many NGOs are staffed by salary-chasing consultants on fat compensation packages who have little knowledge of—or interest in—the country they're working in that year. But as things played out with Maike and Arslanbob, it just seemed like an unfortunate situation all around. I wonder if they're still making cheese in Arslanbob.

(A note about

kurut: although she hated pasteurized cheese, Maike absolutely refused to eat

kurut, on the basis that it was prepared very unhygenically and unless she had made it herself she would be very wary of it. Obviously many people around the world eat it without problems, but apparently the reason it is so salty is that you really need that much salt in order to ensure that it isn't dangerous, like salt-cured meat or fish.)

|

| Uzbek woman coming down from the highlands with a donkey load of milk. |

|

| The big waterfall is up there somewhere. |

|

| In the height of spring I imagine this stream-bed must be a torrent of water. |

|

| On the final scramble to the waterfall viewing point. |

|

| The large waterfall is 80 meters high; much taller than it looks in this stitched panorama.. |

|

| A drunk Kyrgyz tourist insists on posing with me. |

|

| His fellow tourists were more subdued. |

|

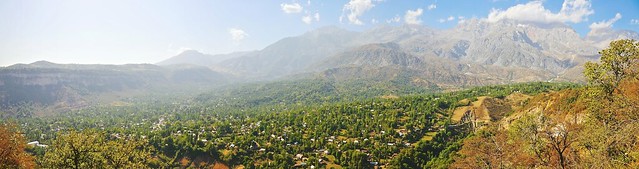

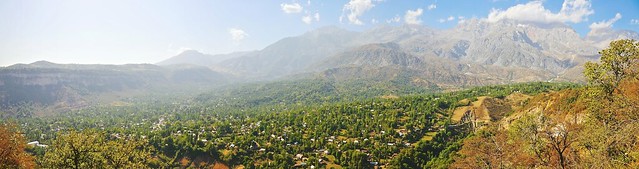

| The southern plateau in the distance. The village of Arslanbob lies at an elevation of only 1,600 meters, which isn't terribly high compared to other places in Central Asia, and thus has lots of trees and a decent climate for raising crops. |

|

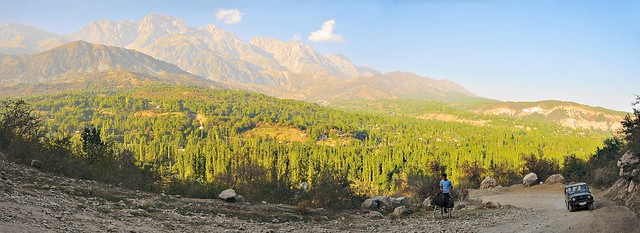

| In many ways the valley feels very Swiss, with lots of open pastures and relatively little tree cover compared to the Canadian Rocky Mountains I'm more familiar with. |

|

| Why do gravel roads feel so much more authentic and exotic? |

|

| This isn't a terribly bad road, so far as Kyrgyzstan is concerned. |

|

| Rough stone fences to constrain livestock. |

|

| Back in town, Uzbek schoolboys say hello. |

|

| The small waterfall is 23 meters high but much wider. It's also much easier to get to, just on the eastern side of the village, with an easy path and a bunch of souvenir stands and snack shops as you approach. |

Both the small and large waterfalls seem to have spiritual meaning, as they are reputed to boost fertility and are adorned with votive scarves. There's also a holy rock located near the large waterfall. All of these shamanistic spiritual sites in the midst of a deeply Uzbek region calls into question my theory that sedentary Uzbeks are less shamanistic and that it's the nomadic Kyrgyz who are more shamanistic and less orthodox in the practice of Islam, but I'm also unsure who the main visitors to these spiritual sites are (the guys who were at the large waterfall with me were definitely Kyrgyz) and when Uzbeks moved to the Arslanbob region.

|

| Haystack above the small waterfall, on the way to the walnut forest. |

|

| Harvesting onions beneath walnut trees. This is apparently the largest walnut grove in the world, and supposedly the source from which walnut trees were exported to the west. |

|

| Arslanbob panorama, with the southwestern plateau on the left, and the mountains with the big waterfall on the right, and the valley with the small waterfall on the bottom right. |

|

| On the way down from the walnut grove. The world's biggest walnut grove looks like a bunch of trees, but the views from the edge are spectacular. |

|

| Precariously stacked hayrick along the path. |

|

| The path down the hill. |

|

| This is what a walnut looks like on the tree. The shell lurks beneath the fleshy green bits. |

|

| Arslanbob from the eastern walnut forest. On the bottom right you can see the path to the small falls, with a row of souvenir shops on the way. |

|

| Uzbek schoolgirls. The classical Krygyzstani (and I assume Russian) schoolgirl uniform is something like a French-maid's uniform, with a white apron over over a black dress. We only see variations of it here, most closely with the girl in red. Notice how they're all wearing pants under their skirts, likely as a result of being Uzbeks. |

|

| The cliff-side road up to Arslanbob's southwestern plateau. |

|

| A hay truck on the way down. Most of the trucks and vehicles up there look like they're over 50 years old: this one looks much newer than most. |

|

| On the way home for the night. |

|

| Harvesting onions on the plateau. |

|

| Typical Soviet truck. |

|

| There are lots of surprisingly lush fields on the plateau. |

|

| Riding a donkey home. I wonder why there were no houses up on the plateau: perhaps the winters are too harsh, and the road too inaccessible? |

|

| You see a lot of cows up here. In the high summer they are kept at even higher altitudes. |

|

| Picturesque tree. |

|

| These guys were digging potatoes when I passed by, and came up to say hi. |

|

| Back to work. Hay, potatoes, corn, and onions seemed to be the biggest crops. |

|

| In contrast to the jeans and T-shirts worn by the men, Uzbek women always wear traditional dress. |

|

| A cow eyes me, and I him. |

|

| It was surprising to see gently rolling hills in the mountains like this. |

|

| Unlike Mongolians or Kyrgyz, Uzbeks aren't great horsemen (and I don't think I saw any horses being ridden), so I wonder why I saw so many in Arslanbob. Milk for the production of Kymys is a possibility, but given that Uzbeks are not much given to alcohol and that Kymys is more or a Kyrgyz drink, I'm not sure if this makes sense. |

|

| I'm used to seeing lots of hay, but always in square or round bales—certainly nothing like these hand-piled stacks. |

|

| Hill-top hayrick in the dying light. |

|

| Without cows there can be no kefir. And that would be a shame—just ask Maike. |

|

| Sunset over the mountains. |

|

| Horses in the valley. |

|

| It's a bit surprising to see dogs in Arslanbob, given how religious the Uzbeks are. |

|

| Young Uzbek women on the way home. |

|

| Old men ride their donkeys home. |

Ethnicity, citizenship, and nationality in CIS countries

At dinner I met the other guest who had showed up that day: he was an older American tourist who had booked a tour through CBT's Bishkek office, arranging for a guide and driver to take him around the country for a couple of weeks, while staying at CBT homestays along the way. He had taken the old hippie trail through Iran and Afghanistan on the way to India when he was younger, and was still able to enjoy traveling some forty years later.

What was more interesting to me, however, was talking to his guide, who introduced me to the foreign concept of "nationality." A couple of times on my trip (including by a border official) I had been asked where I was from, and then asked my nationality. To a Canadian, this is redundant and makes no sense. I'm from Canada, I'm a Canadian citizen, and my nationality is Canadian. But in the Soviet system, nationality is distinct from citizenship, and is used to mean something like ethnicity, except that it is an official category included on identification cards. So although both the tour guide and driver were both Kyrgyzstani citizens, the tour guide's nationality was Russian (a small minority in Kyrgyzstan, and almost all in the north) while that of the driver was Kyrgyz. In places with significant mixtures of nationalities, like the Ferghana valley, it is always possible to tell which nationality someone is from by their ID card, even if they can pass for someone else. For a Canadian, it's easy to see the pernicious uses such a system of nationalities can be put to, as well as how it divides and segregates a country. Of course, this is part of the reason that the system was designed that way, as the Soviets were experts at keeping their populations divided.

On the other hand, I'm sure it makes some conversations much easier. I mean, non-white citizens of places like Canada get the "But where are you

really from?" question all the time, and simply asking for someone's nationality would make the process much more elegant. But I prefer the inelegant, ugly way the question works in English, as it makes it pretty plain what you're really asking, and doesn't flatter the inquirer into thinking it's a graceful question.

Anyway, the guide said that for many people the question of nationality was divisive, but that he thought the country would be better off if they could abolish it and simply think of themselves as Kyrgyzstani (of course, as a Russian minority he probably had a different perspective than Kyrgyz or Uzbeks).

Day three

Arslanbob was a nice place to relax, and since I wasn't feeling 100% recovered from my last day and night in China, I decided to stay another day.

I went to the market, where I looked around and ended up buying some socks. As it happens, Uzbekistan is one of the largest producers of cotton in the world (the Soviets decided it would be a good idea to grow cotton there by irrigating the arid deserts with water from the Aral sea, a decision which has led to the Aral drying up and the shoreline now being dozens of kilometers from where it once was), so they had lots of Uzbek cotton socks. I like flat-knit cotton socks, and it's increasingly difficult to get socks that are more than 75% cotton. At about 60¢ per pair, these black cotton socks seemed to be a pretty good deal, so I bought a few pairs.

A couple of weeks later, when I did laundry in Almaty, this turned out to be a bad idea: these socks were not colour-safe, and they dyed all my laundry into different colours. The effect was anything but subtle, to the extent that when I opened the laundry machine I wasn't sure if someone else had snuck their laundry in. All light coloured shirts—pink, blue, white—were all a light grey-blue colour. A bright yellow shirt was now bright green. Repeated washings would not alleviate the effect.

Down in the fresh area of the market, I met a British cyclist and volunteer from the northern valley of Talas talking with a local beekeeper, who wanted to know how to say certain things in English. "100% pure organic honey!" A real character, and his honey was pretty good. Nearby were piles of potatoes, which I had seen being harvested by hand. They were selling for about 10¢ per kilogram.

|

| A small stream seems out of place in the middle of this pasture. |

|

| Cows amble along the mountain roads. |

|

| Instead of heading up to the big falls, I turned to the left and up a side valley, which led me to a grassy pasture at the top. These high mountain pastures are known as jailoos—"summer pastures"—because they are where the herds are moved in the summer. |

|

| Weird plants on the jailoo. |

|

| Apparently if I kept going to the end of this jailoo I would have eventually run into the holy rock. But since the sun was about to set behind the mountains, I decided it was time to start heading back down the valley. |

|

| View from one pasture to another. |

|

| A herd of horses on the jailoo. It's much easier to understand they are social animals when one sees them running wild, and not in stables. |

|

| Wind-swept tree. |

|

| These mountain streams seem to sprout out of nowhere and incongruously run down the high parts of hills, and not the valleys. |

|

| The sun sets early in the mountainous areas. |

|

| The streams not-so-randomly fork and branch, as they're often diverted for irrigation purposes. |

|

| A last look back at the mountain. |

|

| If you look on the left, you can see a small canal that has been dug into the hillside to channel water. These canals are everywhere and ensure that every house and field has a water supply, and they explain why you see little water channels in unlikely places, and not only in the valley bottoms. |

Budget

September 6, 2012, from Jalal-Abad to Arslanbob: 785 som

- Tandoor chicken shahlyk, coffee, and bread: 90 som

- Share taxi to Arslanbob turnoff: 80 som

- Marshrutka to Arslanbob: 50 som

- CBT homestay: 350 som

- Dinner: 180 som

- Drinks: 35 som

September 7, Arslanbob: 620 som

- CBT homestay: 350 som

- Dinner: 180 som

- Internet: 90 som

September 8, Arslanbob: 600 som

- CBT homestay: 350 som

- Dinner: 180 som

- Drinks & ice cream: 70 som

No comments:

Post a Comment