After four nights and three days resting and recuperating in Osh (after arriving in the city on a cramped four-hour taxi ride I could barely straighten my knee and was seriously wondering if I would need medical attention), I decided to get things moving again and head to Jalal-Abad with a stop in Ozgen.

Although in Soviet times you could go straight across the valley from Osh to Jalal-Abad, the direct route now involves crossing into Uzbekistan before returning to Kyrgyzstan, so everyone now takes the route that skirts Uzbekistan and goes through Ozgon.

In CIS countries, the

marshrutka ("fixed route") is a staple of public transport. In Central Asia they're basically old Mercedes minibuses that have maybe 15 seats that travel a fixed route and pick up and drop off people along the way. Inside cities they can be jammed with people standing anywhere they can, while on inter-city routes they leave when all seats are occupied (though they may pick up standing-room passengers between cities) and not before. Prices are also fixed, and foreigners don't generally need to haggle. Share taxis between cities operate on the same leave-when-full principle, though haggling for prices in these sedans and minivans is essential (not least because many of them are simply private citizens or families making a trip somewhere and hoping to defray fuel costs). An added complexity is that on fares often changes depending on whether there is more demand in one direction than the other and whether there is increased seasonal demand. Perhaps the most difficult thing for travelers is that the places where share taxis congregate and leave depends on where they're going, and can change quite rapidly in ways that guidebooks can't keep up with.

Anyway, the trip to Ozgon was my first experience with marshrutkas, and it was actually quite easy since it left from the central lot near the bazaar, was clearly signed to Jalal-Abad, and only involved a 20-minute wait until it was full. Were that it was always so easy.

Ozgon

Ozgon gets a surprisingly tepid write-up in Lonely Planet, which usually turns on the hype over every little thing that could even possibly be described as an attraction. There isn't a lot to see, with the only real attraction other than its bazaar being an

Karakhanid-era complex containing an 11th century minaret and a 12-century tripartite mausoleum.

Despite being relatively modest in comparison to other Central-Asian sites, in the Kyrgyzstani context they must be some of the most important cultural artefacts that remain in the country, and they remain impressive in my mind for their warm, red, monochrome design and the sympathetic restoration they're been subject too. These aren't the over-the-top reconstructions you see in China or Uzbekistan, but a fairly straightforward mix of modern and surviving brickwork.

|

| The minaret sits next to a parking lot and Russian-style civic buildings. |

|

| Ozgon itself is on a hill at the edge of the Ferghana valley. |

|

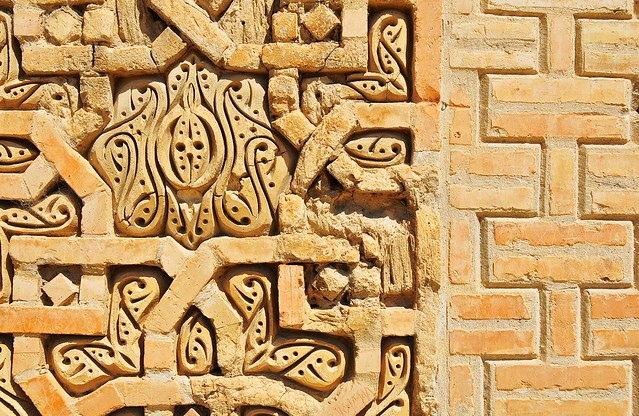

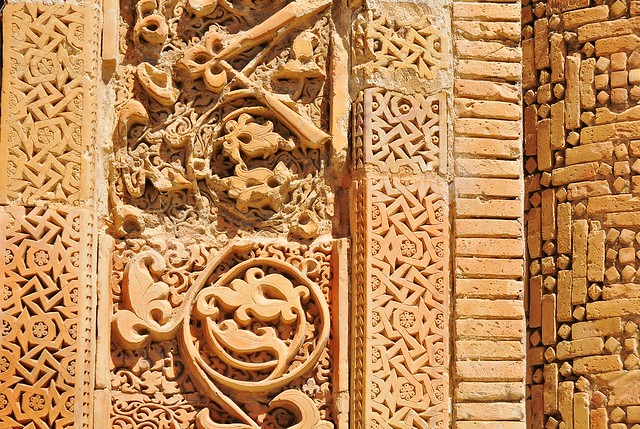

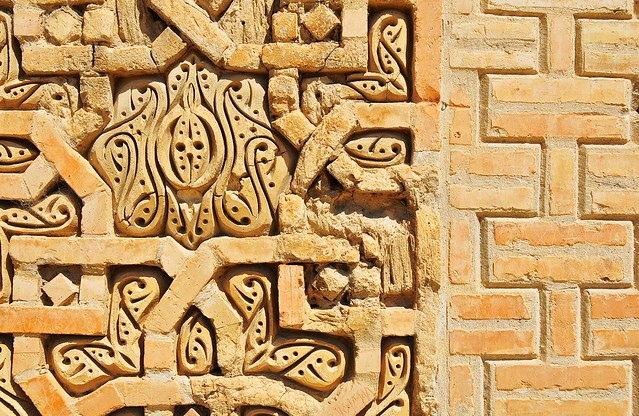

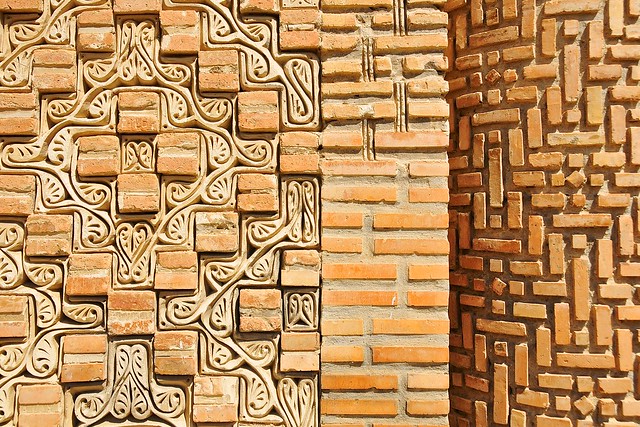

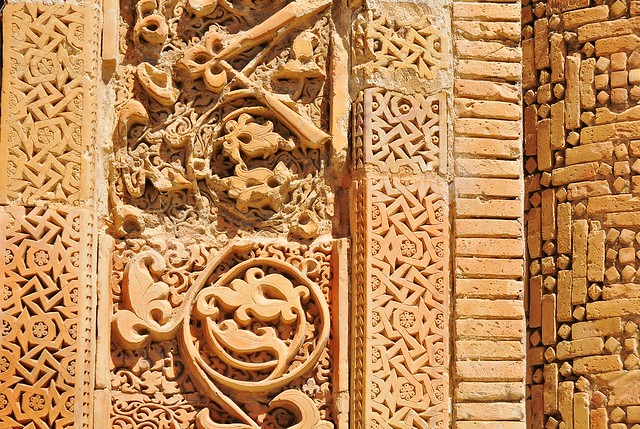

| The ornate brickwork of one of the mausoleum entrances. |

|

| The minaret and mausoleum. |

|

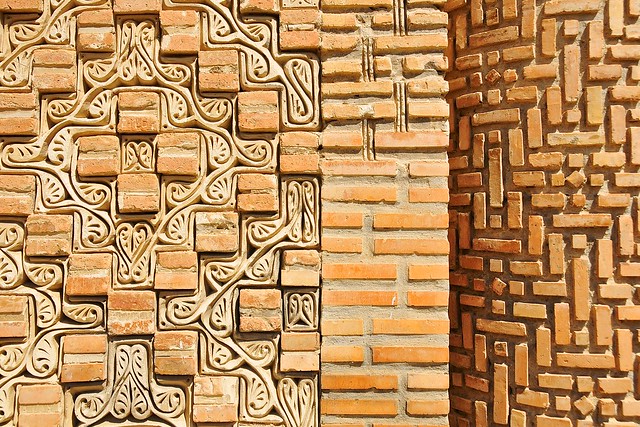

| Detail of the new and surviving brickwork. |

|

| View from the interior. |

|

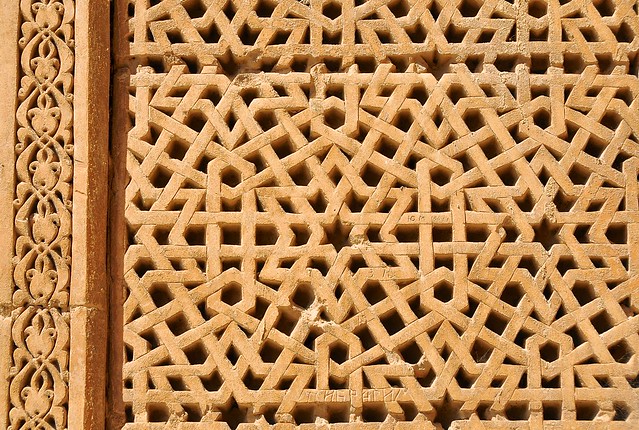

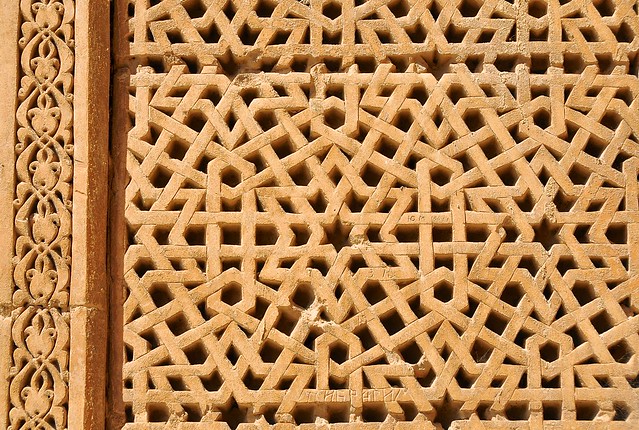

| Strong geometric designs. |

|

| The middle section's facade is almost completely reconstructed, while the outer sections seem to display more original brickwork. |

|

| More of the original brickwork survives in the upper levels. |

|

| In retrospect, I find the monochrome designs to be more interesting than the turquoises you see in places like Samarkand. |

|

| The restorations are just shabby enough to feel authentic. |

|

| Every surface is richly decorated. |

|

| Under the arch. |

|

| I think the scrubby bushes, rough benches, and general decrepitude convey the atmosphere of a typical Russian-Kyrgyz park quite well. |

|

| A modern mosque. |

|

| From the top of the minaret. I was lucky enough that the gate was unlocked and it was open for viewing when I arrived. You can see the foundations of some more ancient buildings on the right. A thousand years ago the views must have been truly magnificent. |

|

| Looking down the minaret steps. |

|

| The mausoleum from the excavation site. |

|

| On the other side of the parking lot is a Russian-style park, with a field of poppies and some trees. Add in the typically haphazard wooden benches, and the net effect is of a park that looks like it was designed to take of itself, under the expectation of benign neglect. |

|

| Uzbek woman walks through the park. |

|

| Shasklyk over smoky coals is a common Central Asian sight. |

|

| I'm the attraction as much as the market is. |

|

| It's easy to spot the Kyrgyz and Uzbek here: bare shoulders, tight pants, and stylish sunglasses mark the Kyrgyz, while conservative dresses are work by Uzbek. |

|

| Headscarf, covered knees, and skullcaps on the Uzbeks. |

I wasn't sure where the Marshrutka stand was, or if they would simply stop anywhere if I flagged them down, so I simply walked along the main road until I found other people also waiting, and joined them.

Jalal-Abad

I arrived at the Jalal-Abad bus station and made my way to what passes for downtown, which is actually on the eastern edge of town. There, I checked into the Soviet Hotel Molmol, torturing the surprisingly tolerant receptionist with my crude attempts to speak Russian. I ended up getting a single room for 335 som, although the bathroom only had cold water. It was still warm enough that this wasn't a deal breaker, but it's certainly not the semi-pleasant experience that a cold-water bathroom in Thailand can be.

I actually don't mind most of the Soviet-style hotels I've been in the rooms have managed to be airy enough, with translucent white curtains on windows that open up onto small balconies (sometimes more decorative and not actually accessible), providing a nice mixture or views and privacy. The furnishings are basic but functional, with retro appeal.

|

| Pistachio grove on the eastern outskirts of Jalal-abad. |

|

| A couple of young girls herd cattle at dusk. |

|

| The road. |

|

| Hilltop near the spa. |

|

| Pistachio tree and Ferghana foothills. |

|

| Beautiful and strange weeds on the arid hills. |

|

| Sheep grazing. |

|

| Since this land is pretty marginal, it's no surprise to see it being used as a graveyard. |

|

| Looking back over town at a shepherd and his charges. Unlike in China and Mongolia, almost all livestock has a nearby herder. |

|

| A mausoleum on the hilltop. The grave markers bear strong Russian influence, as many of the stones display photo-realistically etched portraits of the deceased. Or maybe they do this everywhere now. I don't know, as I don't visit many cemeteries. |

|

| The sun sets through the mausoleum. |

|

| The pollution of the Ferghana valley ensures red sunsets. |

I had decided against the Torugart pass, which meant that I also had to skip Tash Rabat. Tash Rabat, however, sounded very interesting, as it is an old silk-road caravanserai (even though I had no idea what a

caravanserai was, because it's a term that authors like to use without defining, you have to admit it

sounds very interesting) set in a remote mountain valley.

You can get to Naryn, the closest city to Tash Rabat, from Jalal-Abad by a bad mountain road that heads east to Kazarman. Because the road is bad, however, few vehicles take it, and it can be tough to find a ride. Of course, Lonely Planet and its terrible directions on where to find a ride or even get around town is of no help, which is hardly surprising given that Michael Kohn wrote the Kyrgyzstan section of the 2010 edition.

I was content enough to spend a day looking around for a ride while staying in a dirt-cheap hotel room, and I also had the opportunity to get a rare chicken

shashlyk (the Turkic, Farsic, and Russian word for kebabs) made of an entire leg and thigh cooked in a tandoor style. It was a welcome relief from the alternating cubes of mutton and fat that typify Central Asian shashlyk.

I wasn't able to find a ride to Kazarman or Naryn, so I decided to skip it for the moment—I always had the option of seeing it on my way back south—and head to the tourist-friendly mountain valley of Arslanbob instead.

|

| The entrance gate from the main Osh-Bishkek road to Jalal-Abad. I hitched a ride to Bazar-Korgon, he turnoff to Arslanbob, from here. The driver charged me an extortionate 80 som for the short ride. |

I was dropped off at the turnoff, and a curious Uzbek woman running a street-side naan and refreshment stand asked if I was going to Arslanbob and told me I could indeed catch the marshrutka to there from where I was, while also confirming that I overpaid for my ride. It's surprising how well you can communicate despite having no language in common.

Budget

September 4, 2012, from Osh to Uzgen to Jalal-Abad: 610 som

- Marshrutka to Uzgen: 50 som

- Marshrutka to Jalal-Abad: 60 som

- Water: 25 som

- Single room at Hotel Molmol: 335

- Internet: 50 som

- Snacks and drinks: 50 som

- Hamburger: 40 som

September 5 in Jalal-Abad: 585 som

- Single room at Hotel Molmol: 335

- Internet: 80 som

- Yoghurt balls: 10 som

- Hamburger: 40 som

- Grapes: 70 som

- Chips, bread, soda: 50

No comments:

Post a Comment