Like almost everyone—including most of those who travel there—I had no idea what to expect from Central Asia and the 'stans. Whatever expectations I did have as I entered from Xinjiang, however, were confounded by the reality I faced in Osh: although Osh is in one of the most religiously conservative areas of Central Asia—and certainly the most conservative urban area—the overwhelming impression, in sharp contrast to Kashgar, was Russian. The music was Russian pop. The architecture was Soviet Russian, with large communist blocks and stucco houses with tin roofs— no mud brick here. The language was Russian, as it remains the

lingua franca throughout former Soviet CIS (

Commonwealh of Independent States) territories—especially when talking with foreigners and outsiders. Even for the native Kyrgyz and Uzbek language, the script was Cyrillic and not the Arabic seen in Xinjiang. Russian food was back on the menu. Sandwiches, Russian-style hamburgers, and western bread were common, as were cheese and sour cream. Cleaning products—both of the household and personal variety—were a much more prominent section of local supermarkets, and bathrooms tended to bear evidence of their use.

In some ways it was like being back in Mongolia, except the Russian influence was even greater in Osh, and of course in Mongolia I hadn't had a more authentic version of Mongolia to compare Russified Mongolia to, whereas in Xinjiang I had exactly this sort of contrast in Central Asian life.

Another way Osh and Kyrgyzstan resembled Mongolia was in terms of how many people looked. Ethnic Kyrgyz (and Kazakh) look very Asian, and quite Mongolian, which is fairly unsurprising given their proximity to Mongolia and Chinggis Khan's vast empire. Kyrgyz and Kazakhs also traditionally shared the Mongolian nomadic lifestyle and herder lifestyle. Kyrgyz are not very religious and enjoy drinking.

Although in Kyrgyzstan, however, Osh has a majority population of Uzbeks, who—like the Uyghur—are more Caucasian in appearance. Uzbeks are also religiously conservative—especially those in Kyrgyzstan, as the government in Uzbekistan has cracked down on devout Islam in recent times—and dress much more conservatively, with women covering their hair, and men often wearing beards. Between their physical appearance and their dress, Uzbeks look much more similar to Uyghur than Kyrgyz do.

As one might expect, the nomadic, herder Kyrgyz typically live in the mountainous areas of Kyrgyzstan, while the Uzbeks live in the valleys, plains, and other fertile areas where they can farm. Osh is on the edge of the Ferghana valley, at the border with Uzbekistan, and consequently has a majority Uzbek population. It probably would have made more sense to put Osh in Uzbekistan, but under Stalinist border-formation policies, the Soviets thought it best to relocate both ethnicities and borders in order to ensure that the republics would be ethnically divided amongst themselves, as this was thought to be a way from any of the republics ever becoming cohesive enough to unify against the central Soviet government. The result of this government-by-division is that many Central Asian states have ridiculous borders that make little geographic or ethnic sense, as well as significant internal tensions.

Anyway, after getting only a few hours of sleep in an Ulugqat ditch the day before, I was really tired when I arrived in Osh. I was also a little banged up, as I had hurt my knee while taking a fall while running back to the truck I was hitching in (we were stuck in a queue near the border, during which time I ventured a fair distance away; when the trucks started up, I ran back, worried that they were going to be moving more than a hundred meters or so) and I had to limp up the stairs in the hotel. This meant I slept in and took things pretty slowly in Osh, especially since things were so cheap compared to China. 400 som (about $9) for a single room with shared toilet and shower? I was paying that much for a dorm room in Kashgar.

Finally adjusting my watch to Xinjiang time (which is the same as Kyrgyz time), I gained two hours in which to sleep in (which also means I basically lost two hours of daylight), and I took full advantage of this on my first day in Osh. I then moved from the Alay hotel to the Osh guesthouse, mainly because the Osh guesthouse was where everyone stayed in Osh, and was the best place to meet people and get travel information. Osh guesthouse is basically a Soviet-style apartment, converted into a place that sleeps 10 or 12 people. It's noisy, cramped, and hard to find, but its a good place to meet people and the two Uzbek guys who run it are interesting to talk to.

After settling in, I went to explore the city.

Lonely Planet talks up the market quite a bit, describing it as one of Central Asia's largest bazaars and a great place to buy things. In reality, it's much less impressive than it sounds, as it's basically an network of a cuple of parallel shopping alleys lined with stalls that run north-south on both sides of the river, with smaller market squares appearing as little nodes along the alleys. Compared to Xinjiang, it wasn't particularly impressive, and it would be far from my favourite Central Asian market. Probably the most interesting part would be the fruit and vegetable market, which runs on the east side of the river on a pedestrian street, and terminates not far from the Osh guesthouse.

|

| Sewing machines ranged from treadle-operated to modern plastic appliances. Any male wearing a skullcap is almost certainly Uzbek. |

|

| Baby bassinets display obvious Russian influence, with local embellishments (such as the fabric choice). |

|

| Dried fruits and nuts, in an old Russian-style section of the market. |

Heading south from the market, there's a river-side park that follows the river for a considerable distance. This is a Russian-style park, which differs substantially from a Chinese -style park. Instead of artificial ponds and lakes with beautiful common spaces, you have a jumble of trees and dilapidated paths, with scraggly grass and a slightly seedy atmosphere.

Towards the southern end, near the monument to Lenin, there was a small amusement park and Ferris wheel, and an old airplane on a pedestal. I looked around at the plane, hopping up to look inside through the missing door. At this point I was called out by a lone policeman. Uh oh. I immediately figured I was in for a scam, and it seemed likely that he was indeed looking for a bribe. He asked for my passport, and looked through it, while saying something to me in Russian and me asking him things in English while explaining I don't speak Russian. As we did this, I moved so that we were near the main street, and kept offering to go with him to the police station. He eventually let me go, but it left me with a suspicious feeling, especially considering this was my first day in Kyrgyzstan. As it turned out, this was really the last time on my trip I would have any problem with the police, so it was really unfortunate timing.

|

| British pub. We're substantially closer to Rome than Tokyo. |

|

| Lenin statue near the university. |

|

| Kyrgyz wedding in front of a Soviet monument, about a block from the Lenin statue. |

|

| Stretch Hummers, Escalades, and Chrysler 300s were the limos of choice. |

|

| Three-storied yurt at the base of Suleiman-Too mountain. |

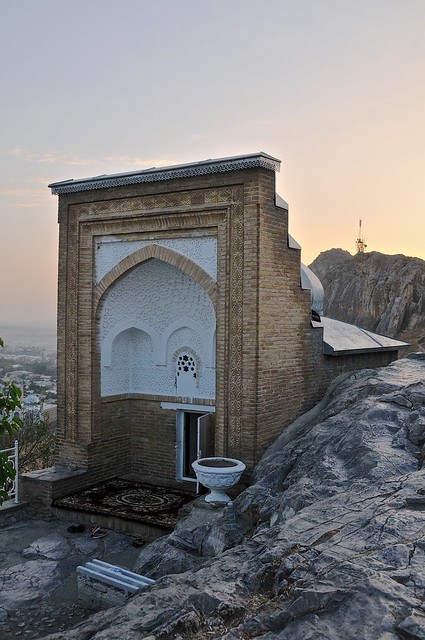

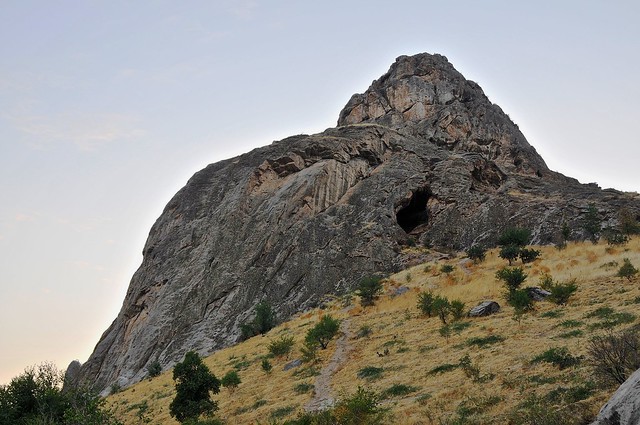

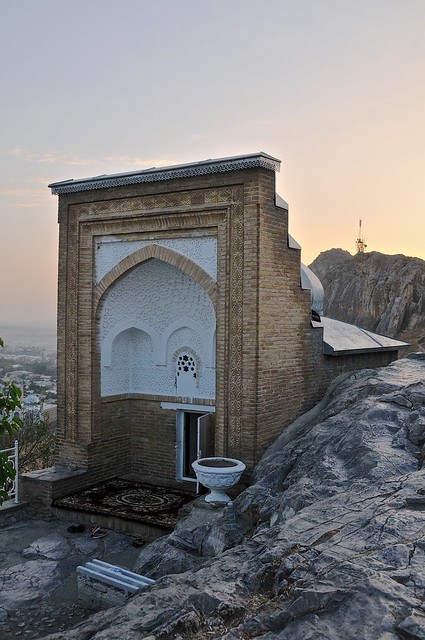

Suleiman-Too mountain dominates the Osh skyline, and is the only UNESCO World Heritage site in Kyrgyzstan. It's a pretty underwhelming experience when you visit, as the main religious attraction is a modern reconstruction of very small mosque founded by

Babur in 1510, the interior of which contains depressions in the stone supposedly worn down from Babur's head and hands as he prayed there.

Read the

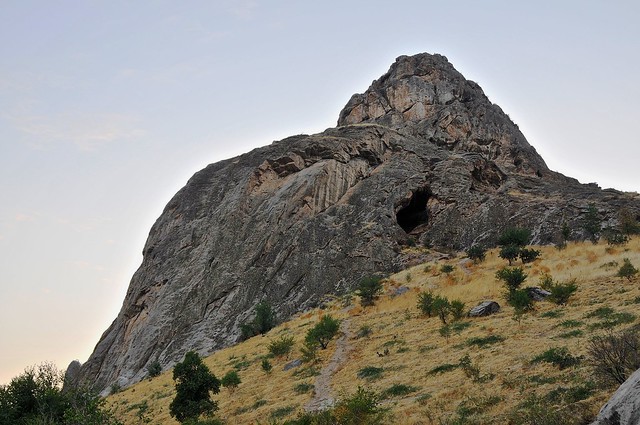

UNESCO writeup, however, and things make a little more sense: Suleiman-Too is being recognized not so much as a Muslim religious site but as a longstanding site of religious significance, and one that has been adapted and re-purposed by multiple religious traditions. Cave shrines and pagan or shamanistic monuments, such as the fertility slides worn into the granite that are used by those seeking children, speak to this mixed religious history.

In keeping with my theory about nomadic peoples and those highly dependent on the environment being more shamanistic and less strictly mono-religious than sedentary people, I would expect Suleiman-Too to have a greater religious importance to the Kyrgyz than the Uzbeks who dominate Osh and the Ferghana valley, but since I had only a dim idea of the different ethnicities—and how to identify them—I don't remember the ethnicities of those I saw on the mountain.

|

| While walking up Suleiman's Peak these two Kyrgyz girls asked me to take their picture, broke out this pose, and didn't even want to see the picture once it was taken. You definitely don't see people dressed like this in Xinjiang. |

|

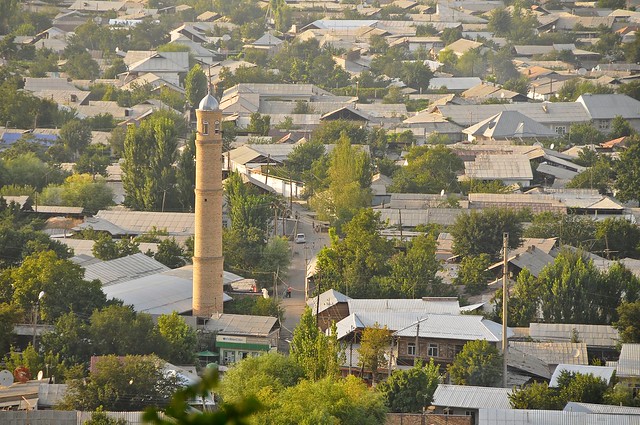

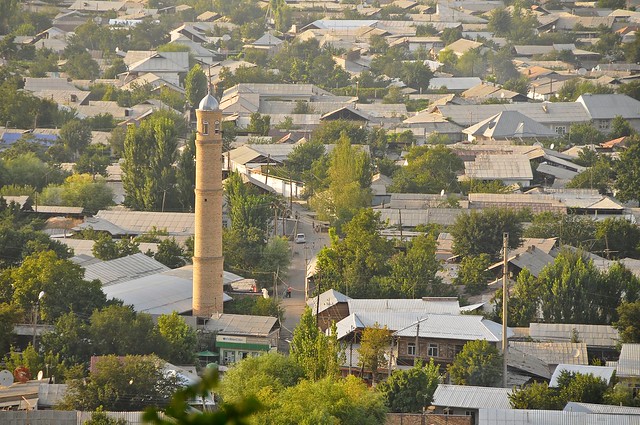

| A minaret to the north of the peak. |

|

| The Suleiman-Too Mosque sits on the southern flanks of Suleiman Peak, with graves lining the slopes. |

|

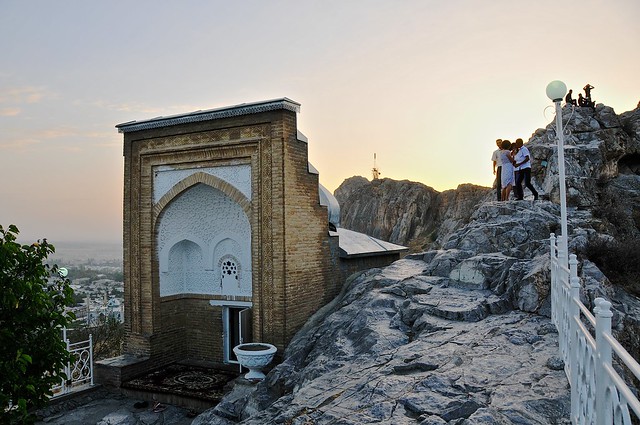

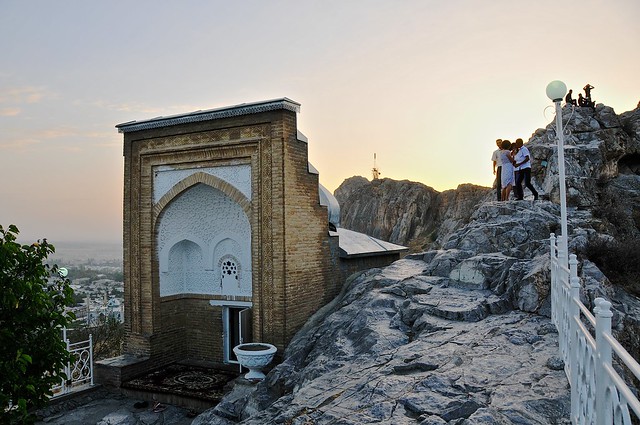

| Babur's small mosque, near the lookout over Osh. |

|

| These stones, polished from centuries of people clambering over them, are surprisingly slippery. |

|

| Looking northwest over Osh. |

|

| It's along this southern path that you'll find most of the caves and the rock slides. |

|

| The craggy peaks are more easily accessible from the north. |

|

| A couple of Kyrgyz and their Lada Niva 4x4. This road, the weather, and the sunset over urban mountains all reminded me very much of sunset at the Griffith Observatory in L.A., three months prior. |

|

| The pattern on the dome seems both Russian and similar to the Durian inspired scales on Singapore's Esplanade building. |

After staying one night at the Osh guesthouse (and taking advantage of their kitchen to cook myself some food for the first time in a long time), and getting some solid travel information but not much sleep, I decided to move back to the Alay Hotel to get some proper rest. I spent a couple of lazy days not doing too much but relaxing and buying foods that hadn't been available in China (kefir and cheese being two big winners).

Budget

September 1, 2012, in Osh: 450 som

- Dorm at Osh guesthouse: 250 som

- Drinks: 75 som

- Pastries: 15 som

- Biscuits: 10 som

- Chips, kefir, water, pears, Kymys: 95 som

- Entrance ticket to Suleiman park: 5 som

September 2, 2012, in Osh: 704 som

- Hotel Alay: 400 som

- Internet: 30 som

- 1 kg peaches: 65 som

- 1 kg tomatoes: 12 som

- 500 grams of cake: 10 som

- Biscuits: 10 som

- Kefir, vinegar: 52 som

- Chips, sprite, chocolate, cheese, coffee, drink mix, eggs: 145 som

September 3, 2012, in Osh: 667 som

- Hotel Alay: 400 som

- Internet: 80 som

- Soda, wafers yoghurt balls: 92 som

- Bread: 15 som

- Shwarma: 80 som

No comments:

Post a Comment