Kharkhorin ended up being one of my favourite places in Mongolia. The main attraction, Erdene Zuu Khiid monastery, is gorgeous and deeply photogenic; the surrounding steppe, hills, and river are beautiful; and I was able to stay in a great, low key, home-style ger camp.

Suvd's Ger Camp & Family Guesthouse

The bus drops you off in the middle of a dirt parking lot just past Erdene Zuu Khiid, and as I got off I a woman gave me a photocopied pamphlet and asked if I wanted to stay in her ger camp, which she said was about 10 minute walk away (they appear to have a rudimentary website,

here). I declined, as I'm always a little skeptical of being approached by touts and there was a ger camp recommended by LP near the monastery. I had noticed when we entered town that I hadn't seen the ger camp where LP described it as being, so after a couple minutes of looking around the empty lot and thinking about it I went back to the lady and said I would stay with her. She flagged a taxi and drove us north to her camp. It turns out that she actually was the owner of the camp listed in LP, but that she had moved since it was published. Unlike some of the massive and institutional ger camps down by the river in Kharkhorin, her camp was simply two or three gers in addition to her family ger in a fenced compound at the northern end of the city. Unlike most housing compounds, the fence around hers was slatted and low, giving it a much more open feeling (given the lack of privacy in traditional Mongolian life, I wonder why they usually use high, solid fences for their homes).

|

| Suvd's ger camp, at the northern edge of town. Doors on gers always face south. |

There is a shower block that has a hot shower, as well as a rather unusual outhouse that has a normal western toilet that flushes mounted on a platform over a pit: it works like a western toilet, but you can hear the flushed water dropping some distance below. She also has internet that goes through a mobile-phone connection, so it's pretty slow but gets the job done. Both the shower and the toilet are cleaned daily.

|

| Unlike Kyrgyz or Kazakh yurts, the central aperture in a ger is supported by two wooden columns. Ropes on the outside let you open or close the aperture. |

Her husband is a tour guide, so he's often away during the tourist season, but she has friendly kids of varying ages, as well as a dog. Dogs in Mongolia are often semi-wild, and not always terribly social. They are used as guard dogs, and they will literally bark for hours on end at night and can be very protective (the customary greeting when you approach a stranger's ger is to shout "hold the dog!"). The barking is really the only way I knew they had a dog, as I never saw him during the day except when I asked her son where it was (it was off sleeping in the shade of the family ger).

|

| Beds line the outer walls and a stove is in the middle. Suvd's daughter is at the computer desk, inadvertently being tempted by the Coke I had left there. |

|

| Mongolian kids are used to strangers, and are passed around as babies. |

|

| She can take pictures of me, too. |

First foray to Erdene Zuu Khiid

After settling in at Suvd's, I headed back into town and towards the monastery, which you drive by on the way into town.

|

| Abandoned Soviet-era plant or factory of some kind. |

|

| Herd of animals between town and the monastery. |

|

| Two goats on the sandy, degraded land. |

|

| Horses also wander around, unhobbled and unrestrained. |

|

| Corner stupas. There are 108 stupas on the walls around the monastery—108 is a holy number in Buddhism. |

|

| Roads run around the monastery. |

|

| A tomb north of the monastery. |

|

| It's very unusual to see a horse's head on the ground in Mongolia. Horses are strong part of Mongolian life and it's considered disrespectful for the bones to be somewhere they may be stepped on. |

|

| Stupas and the mountains to the west. |

|

| These goats used this bus as shelter from the rain. |

Like the goats, I also wanted to escape the rain, so I headed back to the guesthouse for the night. Once there, I met the two other guys staying there. One of them, an American vagabond photographer, had been in Kharkhorin for almost a week. The other, a Chinese Australian, had arrived the day before.

The American was interesting. He had expensive camera gear (think Hasselblad medium format) but was also super cheap and had no definite plans for what to see and do in Mongolia. He figured he would stay three months and work his way west. He also said he had almost been in fights with three Mongolian men who objected to him taking their picture, though he was also drunk on a couple of those occasions. Like most guesthouses, Suvd has a base rate for accommodation only, with higher prices for hot showers, internet, and meals, as well as an all-inclusive price. I think the price for everything was 13,000 togrog. He was too cheap to even pay for hot showers, so he bathed by cold buckets.

The Chinese Australian was also interesting. He was a semi-professional photographer who specialized in women's soccer, and he had been credentialed as a press photographer for Naadam. He said he had attended a ceremony/convention for press, and had met Michael Kohn, the main researcher/author for Lonely Planet Mongolia (and contributing author for the China and Central Asia volumes) there. He had some interesting things to say about him. Apparently Kohn asked him some really basic photography questions, such as why one would spend more money on a fast/wide telephoto lens, and what the point of large apertures was. They also talked about writing and researching for Lonely Planet, and Michael indicated that he did a substantial bit of research by simply reading blogs and then trying to confirm details with a phone call or two. In all honesty, this explains a lot about the book and it's quality. Heck, the back of the book indicates that over 90 days of travel went into researching the book—but you couldn't realistically visit every place listed in the book in a mere 90 days, especially given how slow it is to travel in the country.

Anyway, I enjoyed my hot shower that night and slept very well since I was the only one in my ger. The food was very basic, as Mongolian food tends to be, with all suppers at Suvd's being some minor variation on meat, potatoes, carrots, and possibly onions, either as a soup, with noodles, or with rice.

Day two: exploring the monastery and the riverside area

I Started the day by heading back down to where the bus dropped us off, as this was also the location of Kharkhorin's container market. It's also where the Morin Jim restaurant and guest house is located, and I wanted to check it out. The restaurant may be nice, but the guesthouse portion of it is pretty dreary: it has a couple of gers in a cramped urban courtyard that would be more appropriately used as a parking space, with dirt floors and no grass. There are no showers and the toilets are a couple of long-drop outhouses just next to the entrance. Pretty grim.

|

| Kharkhorin's market is a container market, where the shops are made from shipping containers. |

|

| The shop on the right sells gers. The wooden parts of gers are virtually always orange. |

|

| Motorbiking by the monastery. |

|

| A pilgrim doing a kora around the monastery walls, which involves walking around in in a clockwise direction. |

|

| Goats keep the grass short. Actually, they keep the grass away, since

they tend to pull up grass by the roots instead of just biting it off. |

|

| Inside the walls there are a number of temples, such as this one. |

|

| An inner wall surrounds the three main temples. |

|

| They should let some animals inside to keep the grass short. |

|

| There are some stone turtles outside the monastery and to the north. |

|

| As well as a little shrine. |

|

| Looking back towards the western mountains. |

|

| A large ger sits beside the temples. Interestingly, this ger has its entrance on the east. Supposedly there used to be a huge ger that could seat 300 and was 45 meters across. |

|

| The temples against the mountains. |

|

| A few small buildings, like this shrine, dot the area inside the outer walls. There used to be many more, but they were destroyed with the advent of communism. |

|

| The main temples have been restored |

|

| With fresh tiles on the roofs. |

|

| But it's the older and more dilapidated buildings that have the most character. |

I had planned on entering the temple, but t the last minute I decided not not. Mongolian temples and museums generally have a policy of charging for a camera-taking ticket, and more again for a video-taking ticket. The camera ticket is at least as much as the entry ticket, and in practice this is a way to charge higher prices to foreigners who are willing to pay. I usually don't, and it's not the reason I didn't buy a ticket.

The reason I didn't buy a ticket is because of Mongolian queue jumping. Now, these temples aren't busy, and when I got in line there was only one person ahead of me. As he was leaving, however, an older Mongolian guy just sidled his way to the ticket booth, even though I was just behind the person who bought tickets. The way the ticket lady just ignored the situation even though she had seen me waiting—especially after having this happen repeatedly in China and UB—really annoyed me, and I decided that if they didn't want to sell me a ticket, I no longer wanted to buy one. As I put my money away and started to leave the ticket office, the attendant called out to me and asked whether I had wanted to buy a ticket. Not any more, I said.

|

| Back outside, I saw a Mongolian granny on the way to the temple in her finery. Those huge cauldrons in the mid-ground could boil multiple animals at once. |

|

| It looks like some sort of anti-horse barrier, but I'm not sure what its intended purpose actually was. |

|

| Roof tiles cast long shadows in the noonday sun. |

|

| Mongolian boy poses for his parents. |

|

| The east gate. |

|

| In the Soviet era they used to farm the sandy soil near Kharkhorin. |

|

| Looking north towards the eastern gate to the monastery grounds. |

After taking a couple hundred pictures of the monastery, I headed south. Just past the canal is the new Kharkhorin Museum, which is a really nice museum with some state of the art displays and English-speaking staff who can explain some exhibits. There's also a nice upper-floor lunge just off the museum cafe—the perfect vantage point for for the drama the heavens unleashed, wind and rain whipping the landscape and sending those caught outside scurrying fro cover before blowing away.

After the storm I continued south into the hills over the monastery, where another stone turtle and the penis rock were supposed to be. Climb all the way to the top of the hill and follow the trails to the

ovoo, and you'll find the turtle nearby.

|

| You see fewer motorbikes in Mongolia than you might expect. |

|

| One big ovoo wih six smaller ovoos on the hillside near the stone turte. |

|

| The stone turtle has a small stele on his back and isn't far from the hilltop ovoos. |

|

| Grassy hills after the storm. |

|

| Looking north at the dappled plains. |

|

| One of the more notorious monuments in Kharkhorin is the stone penis, supposedly erected to prevent the local monks from attacking the local women. |

|

| It's behind an ugly little fence now, and was once broken in half. The Lonely Planet direction were predictably useless in finding this, and I relied mainly on the highly-worn path around it, which was easy to spot from the hills above. The American at Suvd's hadn't been able to able to find it in six days of being in town. |

|

| For some reason it isn't popular to advertise to the consumers of Kharkhorin. |

|

| The rain returns. I sought shelter underneath the canopy of the gas station you see ahead on the left. |

After returning to the ger camp for dinner, I went out to see more of the city with the Chinese-Australian. He was extremely capitalistic and right-wing in nature, something that no longer surprises me from Australians. He hated the food (fair enough), thought that the Mongolians should stop using the long-dead Chinggis Khan as the basis for their identity and instead wonder why they've accomplished nothing worth bragging about in the intervening 800 years, and ridiculed the Mongolians for currently wasting land (such as that near Kharkhorin) that had been under cultivation in the Soviet era.

I disagreed. While Mongolian culture may prioritize raising animals over raising crops, I think much of this is dictated by by the quality of land. Maybe you could raise crops on the land near Kharkhorin, but I don't think this would be profitable or sustainable. I mean, you only need to look at Soviet policies regarding growing cotton in Uzbekistan, and the impact it has had on the land and the Aral Sea (which is rapidly disappearing) to see that although something may be

possible under a planned economy, that doesn't really mean that it is efficient. This agricultural and infrastructural poverty has had a lot to do with why Mongolia hasn't been able to do a lot since Chinggis Khan, and it also explains why Chinggis Khan was able to accomplish everything he did—the historical record indicates that there were very mild winters and wet summers in years leading up to his empire, while Mongolian horsemanship that a nomadic lifestyle demands resulted in strong and capable warriors and cavalry. And even though Mongolia's current resource boom holds great promise, their infrastructure will remain problematic, especially since they are worried about either Russian or especially China gaining too much influence and using any new infrastructure as a possible way to subjugate Mongolia.

|

| The southwest edge of town, near the Imperial Map Monument, which depicts the former extent of the Mongolian empire. It's true that Mongolia lives deeply in the past glory of Chinggis Khan. |

|

| The great ovoo inside the Map Monument. |

|

| Looking south towards the Orkhon Valley. |

|

| The wide plain of the Orkhon valley from the Monument. |

|

| The setting sun. |

|

| Horse skulls decorate an ovoo: a fitting resting place. |

|

| Gers and herds on the other side of the valley |

|

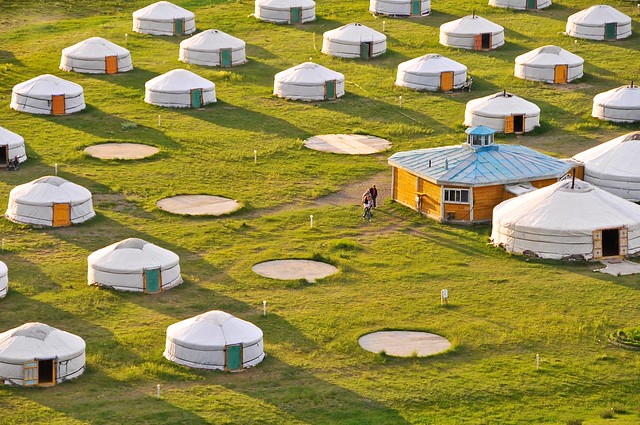

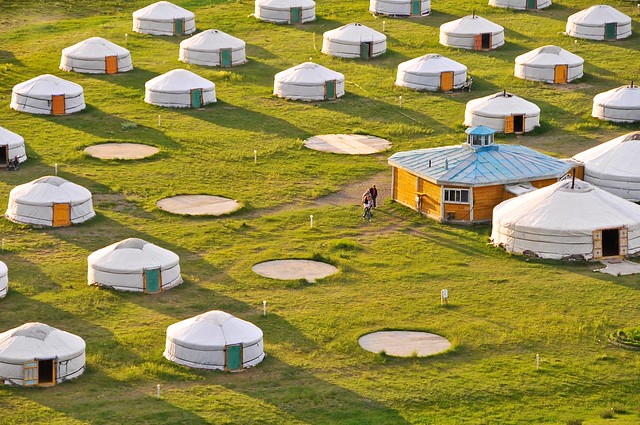

| Panorama of the Orkhon valley. A small dam lies behind the central ridge, and in the valley on the right there are a number of ger camps. |

|

| Most ger camps in Kharkhorin are large and institutional. |

|

| Locals picnic by the Orkhon. |

|

| The Orkhon winds its way through the valley. |

|

| Hundreds of four-footed lawn mowers keep the grass short. |

|

| The little dam can be seen on the right. |

The dog barked long and hard that night, making it difficult to fall asleep. I walked out to the toilet a few hours after dark, and was stunned by the sight of the stars and Milky Way. It was almost the new moon, so there was little competition in terms of lunar illumination, and I couldn't remember the last time I had ever seen the stars like that: the Milky Way looked as clear and bright as it does in long-exposure photographs. Even in the town of Kharkhorin, there are almost no lights at night and no other light pollution for hundreds of kilometers around. It was a spectacular sight, and the best view of the stars I had on my entire trip. Truly an amazing way to cap a wonderful day.

Day 3: hiking the ridges west of the Orkhon

On my second full day in Kharkhorin I decided to walk around and climb the hills around the town.

|

| Looking south over the bridge into Kharkhorin. |

|

| A black sulde spirit banner is usually used in wartime. Buddhist swastika design in the stone base and an animal pelt tied to the sulde pole make this a definite mish-mash of Buddhist and animist symbols. |

|

| A skin is tied to the sulde. |

I started out climbing the side-valley that contained the

sulde.After clambering up to a ridge overlooking Kharkhorin and the Orkhon, the flies started to make the presence known. There were hundreds of the, everywhere you went. They would fearlessly perch on you, and if you waved them away they and their friends would alight on you again just moments later. I think it's a complete failure to understand this type of swarming that makes Westerners wonder why people don't simply shoo flies away when they're shown images of starving Africans covered with flies. They were as annoying as shit, but at some point you just have to get sued to them.

|

| Panorama from ridge. |

|

| Looking down at the grassy Orkhon valley |

|

| Gers, herds, the Orkhon, and mountains. |

|

| View from the edge of the mountain. |

|

| Most roads in Mongolia are like this. |

|

| View from the Orkhon valley. |

|

| Goats at work. |

|

| Goats smell like they taste. I prefer sheep. |

|

| The Mongolian, goat equivalent of a bell-wether. An apron-ram? |

|

| The livestock don't really mind me, but they keep about ten feet away. |

|

| This mother and child were stragglers. |

|

| The dam on the Orkhon, and a couple of SUVS parked for a barbecue on the other side of the river. |

|

| The dam is used to divert water into an irrigation canal. |

|

| The Orkhon above the dam is littered with backwaters and false channels. |

|

| A little slice of paradise. Bug-free in the valley, too. |

|

| The backwaters are very still. |

|

| The still water and wetlands attract more birds than I saw anywhere else in Mongolia, including these Demoiselle cranes. |

|

| That's the Map Monument up there on the hill. |

|

| A Ruddy Shelduck. |

|

| A Common Tern. |

|

| Mongolians parking by the river, with a blue tent (likely a foreigner) further up the river. |

|

| Reflecting pool. |

|

| The valley is riddled with these little channels. Unless you want to walk around them, it's best to throw you shoes to the other side and wade across. |

|

| The Orkhon floodplain. |

|

| Though beautiful, these still backwaters breed mosquitoes that come out as it gets darker. |

|

| Picnicking by the river. |

|

| Take off your shoes and you can walk along the dam if you are careful. |

|

| A boat-shaped dining area sits just below the dam, attached to one of the ger camps. There are lots of ger camps in the area, including one owned by (former) Sumo Yokozuna (grandmaster) Asashoryu. It's a luxury camp aimed at Japanese Tourists, and has attached bathrooms for each ger. |

|

| Grazing in the valley, below the Map Monument. |

One last visit to the monastery

Although I had a great time in Kharkhorin, I knew I had seen everything there realistically was to see in town, and I don't like to not be busy when I travel. Days off tend to feel like wasted, boring days. So, after trying to buy a bus ticket myself—but being utterly unable to find out where they are sold—I asked Suvd to buy me a ticket for the next day and incurred her modest commission.

After having dinner, it was time to take a final walk to the monastery before I left early the next morning.

|

| Approaching from the west, under the power lines. |

|

| Power plant to the north. |

|

| Through the western gate. |

|

| Looking south along the kora path. |

|

| The western gate in the warm evening light. |

|

| The northern gate. |

|

| The setting sun. At these latitudes it stays light for quite a while after sunset, as the sun hovers below the horizon. |

|

| A crow heads to its roost. |

|

| You can see in the eastern sky where the sun's rays still shine, and where it has set. |

|

| The inky blue of post-sunset twilight. |

|

| Gorgeous purple hues where the sun's last rays shine. |

On the way back home I passed by a prison. High chainlink fences topped with barbed wire, and dozens of men being led in from the fields. They looked as curious about me as I was about them.

|

| The rain from the day before had turned the bumpy dirt roads into ponds and pools. |

|

| As I took the foregoing picture a drunk showed up and insisted I take his picture, posing somewhat awkwardly. He was satisfied when I showed him his picture, and stumbled on his way. |

LOL! Your comments on the American, and the Canadian-Australian, and the tag on Michael Kohn are hilarious.

ReplyDeleteThanks so much for all the details in your blog (particularly regarding the bus to Kharkhorin.) I have a couple questions-- could I email you?

I had the misfortune of reading a lot of chapters by Michael Kohn on my trip, and was led astray on multiple occasions. He sucks. At least the American was bathing though, unlike some of the folks who seem to think that the only way to authentically experience a rugged place like Mongolia is by not bathing.

DeleteYou could probably ask your questions here, or shoot me an email. Not sure how much help I could be since my info is going to be out of date.

I know what you mean! (about the bathing) Seen that the world around. I'm not a religious bather, but its not too hard to keep my body odor in check.

ReplyDeleteThough things may have changed, I had some questions about Kharkhorin. Heading west along the Orkhon River is one of two routes I'm considering for an independent horse trek w/my partner. Most of very few resources say that you can buy riding supplies at the black market in Ulaanbaatar, but I wondered if you saw any evidence of horses and supplies to rent or buy around Kharkhorin? Like... are there families in the area I could possibly proposition to rent horses and saddles from for 10-14 days? I don't expect you to know for sure, just wondering if it seemed plausible based on your time there? Not asking for guarantees by any means.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThe Black Market in UB is just a big market with lots of stuff. I expect local markets offer riding supplies since this is something that locals are likely to need, and you could probably buy horses and supplies and sell them afterwards. You might be able to rent if you can overcome the language gap and speak directly with locals (English speakers at your ger camp or whatever are more likely to direct you to their own tours and services, and I think this is probably the easiest option).

DeleteSuvd's husband runs horse tours, and maybe he would rent you horses and equipment, and feel more comfortable doing so (I suspect that locals would be skeptical of getting their horses back, and would rather sell).

http://horsetripganaa.com/

Gaya's guesthouse also runs tours and her website is pretty informative.

http://gayas-guesthouse.strikingly.com/

I've heard of people buying horses and selling them in Kyrgyzstan, while in Mongolia it seems more common to buy motorbikes and sell them afterwards.