Fear, paranoia, and suspicion are everywhere in Beijing. X-ray machines in subway stations. Scores of plainclothes policemen in Tiananmen square, which contains numerous official police security stations but no place for people to sit or congregate comfortably. Security officers with fire extinguishers next to the Tiananmen Gate and it's monumental portrait of Mao, in anticipation of Tibetan self-immolators. It's clear the government is worried, fearful of internal dissent from Tibet and Xinjiang, fearful of any organized uprisings against the government for any reason whatsoever—be it lax responses to earthquakes, as in 2008; train crashes as in 2011; or any of the scores of cases of local corruption that occur every year. The government lives in fear of its citizens, and this fear is as palpable as the US fear of terrorism. But unlike the US fears, which manifest themselves mainly when flying, reminders of Beijing's fears are omnipresent.

|

| Making sure no one sets themselves on fire. |

|

Because it would look bad for this

to happen before Chairman Mao. In order to minimize the chances of this

happening, most of the area is roped off and the throng of people means

you have to keep moving.

|

|

It's difficult to imagine a less

inviting public space than Tiananmen square. No respite from the sun, no place to sit, and plenty of plainclothes minders to keep an eye on you. There's definitely no

lounging, dancing, or Tai Chi that goes on here, as it does in most other public spaces in China.

|

|

At the iconic CCTV building, by Rem

Koolhaas, you can't even get near the building as there is strict

security and fencing around the perimeter. This is definitely not

architectural tourism like Gehhry's Guggenheim Bilbao or Disney Center. China may be the source of great commissions, but it must be disappointing to have an amazing building get built yet not have people fully enjoy it. |

|

| The most accessible interesting architecture may be commercial buildings like this shopping mall west of the Forbidden City. |

|

| Or in the trendy students' area of Sanlitun. I love Uniqlo and this

building was pretty cool, but the inside of the glass-curtain wall was

black with streaks of dirty rain pollution. |

Just 10 years ago, the dominant stereotype of Beijing was of a city where bicycles ruled its flat, wide streets. Today,that's simply not the case. Car traffic is horrible, and made worse by the driving habits of the Chinese. Traffic lights seem more advisory than anything else, and crossing streets as a pedestrian means not so much as following the lights as following the crowds. Audi A6s seem to be the most highly preferred luxury cars, but Buicks run a surprising second. Electric scooters outnumber bicycles by a wide margin, and in fact you don't really see any bicycles whatsoever.

|

| Luxury Buick. The sticker on the hood says "Fuck You," but I believe you'd get the message simply from the way he drives. |

While scooters may help reduce pollution in Beijing, the huge number of cars certainly don't help (even if the majority of the pollution comes from outlying factories and industry), and the effects of the smog were greater than I had imagined. I mean, I had read about how bad the smog was, and how unhealthy it was considered, and I had heard about how it could be difficult for Olympic atheletes, and I had seen the air-quality-related health warnings, but nothing really prepared me for how it would actually feel.

I tend to be quite healthy. I get sick maybe once every three years, and I've vomited maybe twice in the past 8 years. So I certainly wasn't expecting to feel any ill effects from smog that millions of Beijingers survive every day. But I began feeling the ill effects on my first day in Beijing. I didn't notice it at first, but by the end of the day I realized that inhaling through the nose was making me feel like the air was corroding the back of my throat. By the second day I had developed a cough. This cough ended up persisting for over two months, despite taking cough drops (Hall's is available in China and Mongolia) and western medicines recommended by Chinese pharmacists.

Visually, the smog was so extreme it was difficult to believe it was the height of summer, and that the days were some of the longest of the year. Though it might not get dark until close to 9:00, it would start to feel dark much earlier in the day—perhaps as early as 5:00.

Hutong

My first few days I stayed at a highly rated Hutong guesthouse located just north of Jingshan Park: the

Sitting on the City Walls hostel. I was pricey, at 100 yuan for a dorm bed, but the location is great and the experience unique: you truly are in the middle of a traditional hutong, inaccessible by car.

One of the people in my room was a Chinese girl in her 30s who spoke excellent English and was traveling with the English Lonely Planet China. Despite this, I'm pretty sure she was Chinese by the way she acted: despite sharing the room's ensuite bathroom with 7 other people, she would spend one hour in the shower, and she would regularly leave the door wide open whenever she left the room, despite the room opening up onto the communal courtyard. On the morning I went to Mutianyu, I got up before 6:00 to make sure I would make the bus, and as I sat in the courtyard I noticed she kept leaving the door open as she went in and out. As she was about to leave the hostel, I asked her if she would mind closing the door to the room, as people were trying to sleep. She got quite angry and told me that if it was such a big deal to me, maybe I should get a private room, and then left the hostel without closing the door. I think this answer encapsulates the different perspectives that Chinese and Westerners have: I would think that if you can't be considerate of others, perhaps you should get a private room; she thought that if others can't tolerate her lack of consideration, they should get private rooms.

Anyway, staying in a hutong means you walk through them regularly. It's difficult to tell what life is like, as most everything is closed off behind courtyard walls, so the only thing you really see in the alleys are doorways, come parked bikes, and people walking to and from home. Sure, they have character, but it's tough to know what life is like. I'm not sure life in most of these old hutong houses is great: they weren't designed or built with modern electricity or plumbing in mind, and based on the public bathrooms I've seen in hutong alleys I believe that many of them lack plumbing for sewage. In this context, it's easy to understand why so many are being destroyed. The "preservation" solution seems to be the destruction of the old hutong and the replacement with modern versions of the buildings. Unfortunately, this will involve displacing residents, as the replacement buildings are luxury buildings that can only be afforded by the elite.

|

| One of the new & expensive luxury hutong districts, located on a refurbished canal. |

|

| Beautiful, modern, and only for the elite. |

|

| A more traditional, and modest, hutong wall. |

|

| Through a hutong doorway. |

|

| The Bell Tower and Drum tower are in heavily-touristed hutong areas, with wider streets and more commercial appeal. |

|

| View under the bell towards the drum tower. |

|

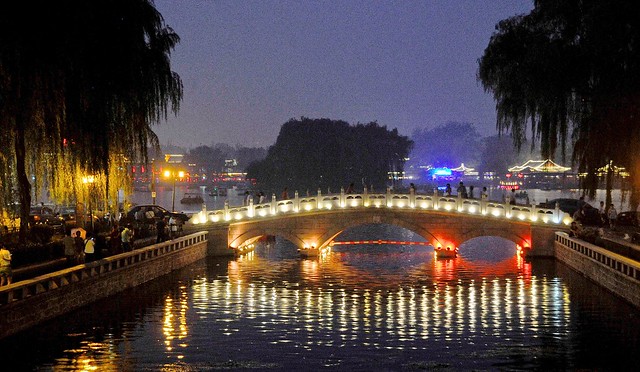

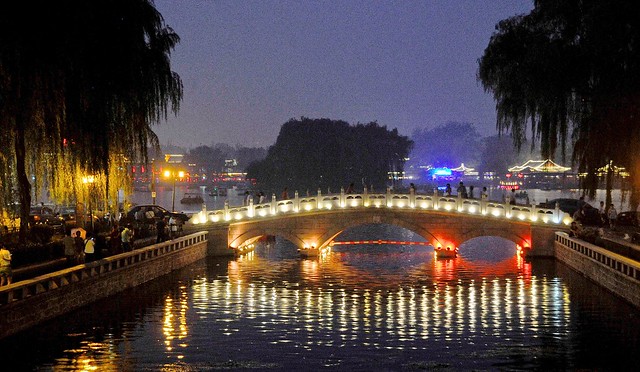

| Looking

towards Qianhai Lake (one of the lakes north of Beihai) at night. The

Bell and Drum Towers are to the north, on the right, while the

canal-side hutong are behind me. |

|

| Stores near Nanluoguxiang,

a super trendy shopping street that presents itself as a hutong alley.

It's really little more than a shopping mall, though there are some more

authentic hutong alleys running off of it. |

My first—and completely unwitting—exposure to Uyghur culture happened on Nanluoguxiang, where I bought some meat skewers at a food stall that seemed very popular. It turns out, these were intended to be Uyghur kebabs, which are popular with Han Chinese. Indeed, Chinese will tell you they're not biased against Uyghurs because they love skewers and Uyghur women are renowned for being very beautiful. This is a bit like saying Westerners can't be biased against Asians because we love Chinese/Japanese/Thai food and fetishize Asian women. Anyway, the skewers were decent, but not really authentic: as they were less than 40% fat, and not all of them were mutton.

Peking Duck

This being the home of Peking Duck, I had to try it while I was there. I went to one of the highly-recommended places, and in the very least I can say it was popular with the locals, as there was a 30 minute wait and not another foreigner in sight.

The duck was a very reasonable 88 yuan for a whole duck at

Jinbaiwan. The bring out the duck already carved, and ask you how you would like the bones. I didn't quite understand the options, but ended up getting them in a soup. I've never had Peking Duck before, but it was interesting. The skin is extremely crispy and is recommended to be eaten with sugar. The meat is eaten in little wonton-style wrappers, like a tiny taco or burrito, after being seasoned with a hoisin sauce and garnished with cucumber, spring onion, and possibly other stuff. The sauce they use is extremely salty and overpowering to a Western palate, and the experience wasn't as revelatory for me as it seems to be for some.

The more interesting thing was being seated with a Chinese couple at a large round table (as I said, they were busy, and I was alone). Here I got to see Chinese-style dining, which may be as much about showing off as it is about eating. There were only two of them, but they ordered the deluxe duck with seasonal fruit, a huge salad, soups, and a few other dishes. Given how little they ate, it seemed like an exercise in conspicuous consumption. I know it's rude in Chinese homes to eat everything off your plate, as it shows you weren't given enough to eat, but this was the opposite: barely touching anything.

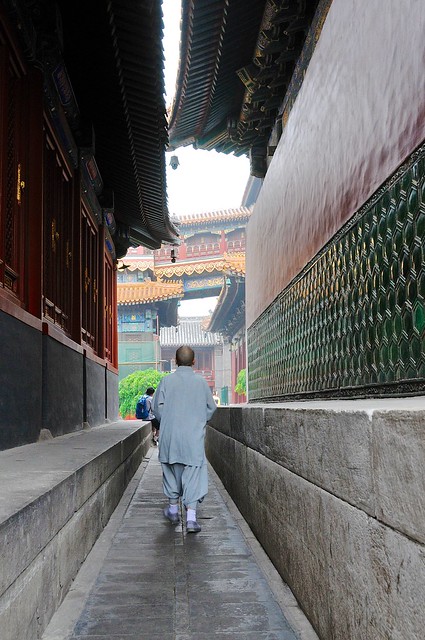

Lama Temple

The Lama Temple is Beijing's Tibetan temple, and is supposed to be the largest Tibetan temple outside of

historic Tibetan lands (which includes not only the Tibet Autonomous Region but Qinghai, and parts of Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan).

Chinese are interested in Tibet, and I think that part of their interest is due to the religiosity of Tibetans; any real understanding or conception of religion has been virtually eradicated in the Han through Communism and the Cultural Revolution, so the idea of people who are devout Buddhists and who practice a variant of traditional Chinese beliefs is interesting to them, even if they don't really believe that those beliefs deserve respect (or understand why they deserve respect). In many ways the Chinese who visit (non-Tibetan) Buddhist and Confucian temples in China are just as ignorant as any western tourist, and lack the context in which to understand these buildings—but because of their lack of exposure to any religion, they are even less respectful than foreigners, and seem to treat these temples as mere curios.

Anyway, while Lama Temple may be the biggest temple outside of "Tibet," it's really only a pale—and Sinocised—version of what you'll see if you actually go to traditional Tibetan lands: don't sweat it if you don't have time to see it.

|

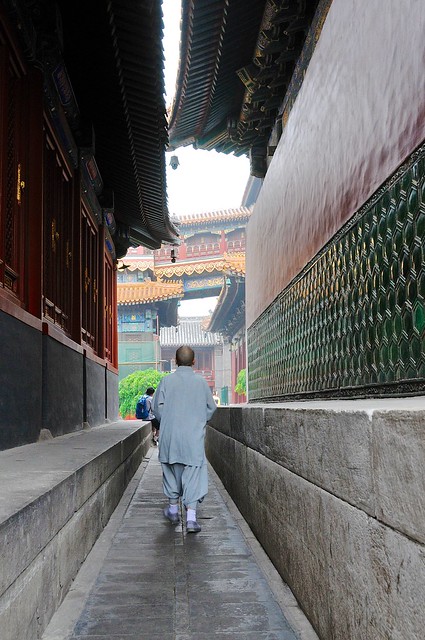

| Looking down an alley between the many buildings in the complex. |

|

| Incense burns before an altar. |

|

| A monk makes his way. |

|

| A reflection in a water cauldron. |

|

| An interesting altar. |

|

| A prayer wheel in action. |

|

| One of the main halls. |

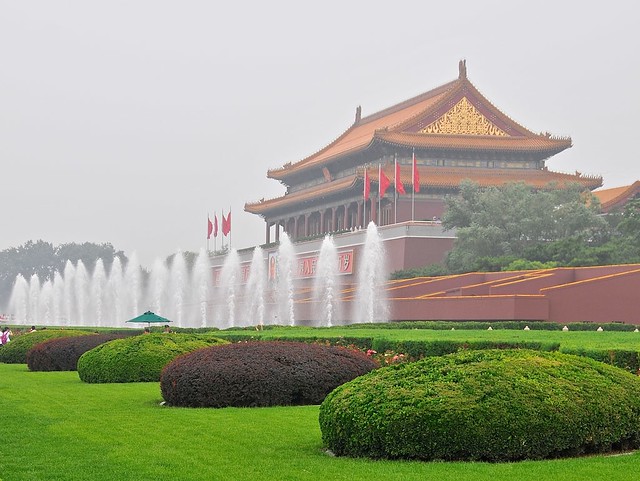

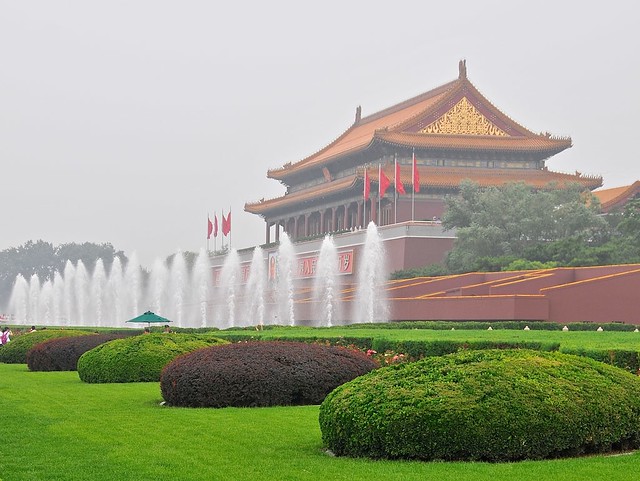

Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden City & Jingshan Park

These three sights are arranged on the same axis, and run from south to north. Tiananmen square at the southern end is a large, soulless, empty square where people assemble to have their pictures taken and where the only people that linger are the uniformed and plainclothes police. It's flanked by large, oppressive, and characterless government buildings. You have to pass through security screening to even enter the square.

Just north of Tiananmen is a wide boulevard of 8 lanes of traffic; pedestrians cross through subterranean tunnels. I can only imagine what security is like now, after the

2013 car crash in front of the gate.

|

Tiananmen Gate from near an underpass.

|

Next up is the Tiananmen Gate, a massive and imposing gate decorated with a huge portrait of Chairman Mao. Security here is also tight, and you can only walk along narrow, fenced-off paths.

|

Guarding Chairman Mao.

|

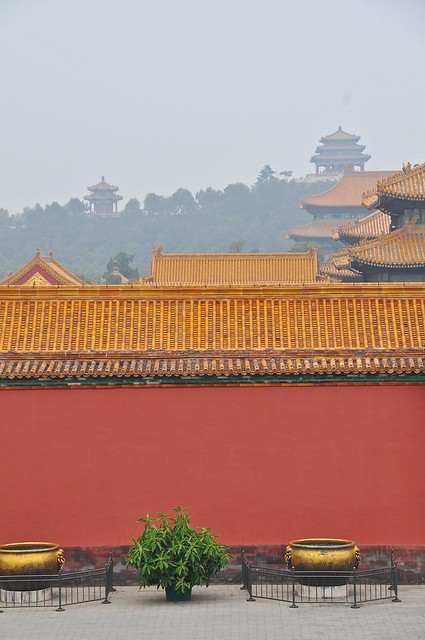

The Forbidden City

Proceeding north, you'll pass through a plaza before hitting the entrance to the Forbidden City. The ticket queues are huge, and it took about 45 minutes to buy my ticket. Most people wait patiently in line, as I did. But some people will push to the front, bypassing the queue (it seems that elderly soldiers or Party members are permitted to do so), and there are some people who do this professionally. If it was Canada, I would have stopped the queue-jumpers, but no one else in line took any action, even though it was evident that some were also frustrated. What was even more annoying was that the ticket-booth operators would continue to sell this same person ticket after ticket, even though he was clearly jumping the queue and appearing every minute or so to push aside legitimate customers. He only stopped when there was a change in booth attendants and the new attendant refused to sell him tickets.

By the time I bought my ticket I had observed people behaving badly for almost an hour, and was not in the greatest mood. I mean, it especially makes no sense given how China claims it wants to reform how people act and encourage queuing and orderliness while discouraging spitting and littering, yet they allow and this kind of queue jumping at their flagship tourist attraction that hundreds of thousands of foreign tourists also attend. Even train station ticket lines have anti-queue-jumping turnstiles installed; why not use them at tourist sights if the ticket sellers are too feckless to do anything?

Although this definitely coloured my perception of the Forbidden City, I still don't think it's a great experience. It's a very crowded, fairly expensive (60 yuan) collection of old buildings with little to no expository information and little educational value. There is relatively little that is exceptional about the complex other than its size, especially all of the buildings and sub-complexes are stylistically similar. I'm not sure if the experience is substantially better than watching

The Last Emperor.

|

The northern gate of the Forbidden City is the exit. You have to walk around to the southern side to find the entrance.

|

|

View of the Forbidden City from across the moat to the west.

|

|

| The southwestern end of the moat, next to the entrance. |

|

Just inside the entrance. The Forbidden City is huge, crowded, makes a lot of money, and offers little in exchange.

|

Many Chinese sights have huge entrance fees. 60 yuan is comparatively low, but even that is pretty expensive given the quality of what is on offer, the number of people who visit, and the overall cost of things in China. In other places, it is just ridiculous: 150 yuan for the Terracotta Warriors in Xian, and similar amounts to enter some national parks. These prices would be questionable in the West, and are crazy in China, since they are about my daily budget.

Prices of Beijing attractions can be found

here.

|

| Below the Hall of Supreme Harmony. |

|

| Courtyard of minor complex. |

|

| Bronze water cauldron. |

|

| Bird sculpture against the Hall of Supreme Harmony. |

|

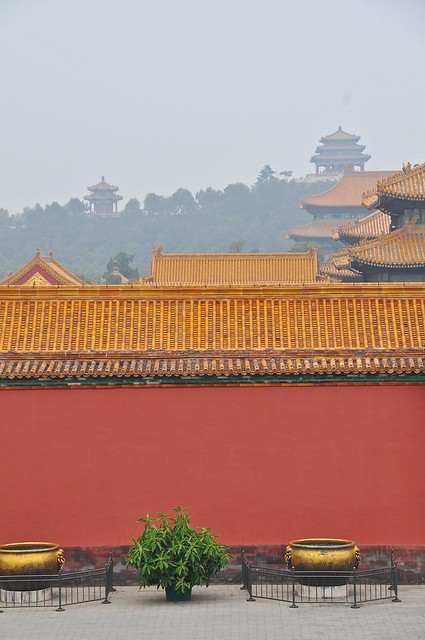

| View of Jingshan Park from northern end of Forbidden City. |

|

| A tree sprouts on the roof. Most of the palace is poorly restored, and the interiors totally inaccessible. |

|

| You can only peer into most palace buildings through dusty windows. Beihai Park's stupa can be seen in the background. |

|

| A green tile wall contrasts against the red walls. |

|

| Green bamboo contrasts similarly. |

|

| Bamboo in the imperial garden near the exit. |

|

| Also near the exit is the most evident investment into the Forbidden

City. No, not a museum or exhibit, or fresh restorations, but a way to

kitschify the experience while extracting more money. |

|

The northwest corner of the Forbidden City.

|

|

The disrepair and decrepitude of the buildings facing the country's greatest tourist attraction is pretty surprising.

|

|

These phone booths are pretty funky, and almost as obsolete in China as they are in the West.

|

Jingshan Park

After exiting the Forbidden City at it's northern end, Jingshan Park is directly across the street. There are apparently only three hills in all of Beijing, and Jingshan Park is the location of one of them. Climb it, and you're afforded nice views of the Forbidden City and Beihai Park (smog permitting).

Comparatively few people continue on to Jingshan Park after they leave the Forbidden City, and entrance is free, which means that locals use it as a place to walk, socialize and relax. It also has interesting pagodas and vantage points, which makes it more interesting to me, as does the abundance of vegetation.

|

| Water lilies in ceramic planters near the park entrance. |

|

| Through the smog. |

|

| From Jingshan towards Beihai stupa. |

|

| Along the axis of the Forbidden City, with the Jingshan entrance and Forbidden City exit in the foreground. |

|

| They have dinosaur sculptures at the bottom of Jingshan Park. The leaves in the mouth are a nice touch. |

|

| Towards the top of Jingshan. |

|

| Looking back towards Jingshan from Beihai. |

Olympic Park

The most accessible and photogenic modern architecture in Beijing is probably at Olympic Park, just north of the fourth ring road, and the buildings show themselves off to their best advantage at night. Despite this, the subway line running to the Olympic Park closes earlier than the rest of the subway network, as the last southbound train on the line leaves at 10:00 and arrives at Olympic Park at maybe 10:20 or 10:30. (Other lines generally run their last train at around 11:00.)

In order to remind people to leave—or in recognition that people have already left—the lights are turned off at Olympic Park shortly after 10:00. It seems a strange way to treat a premier attraction.

|

| The Bird's Nest stadium, by Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei, It's across from the Water Cube, and the plaza that separates them feels more like a real public space than anything around Tiananmen. |

|

| Detail of the latticework. Unlike most things that can be illuminated, the colors on the Bird's Nest do not change. |

|

| It's a surprisingly inviting and elegant building. |

|

| But unlike the Bird's Nest, the Water Cube changes colours (except for those two bubbles that are stuck on blue). |

|

| Like the Bird's Nest, it's also a gorgeous, whimsical building. |

|

| It's kind of hard to see through the blue, but after only 4 short years there is considerable staining and streaking on the panels. |

|

| I would have expected many more people to be visiting every night. |

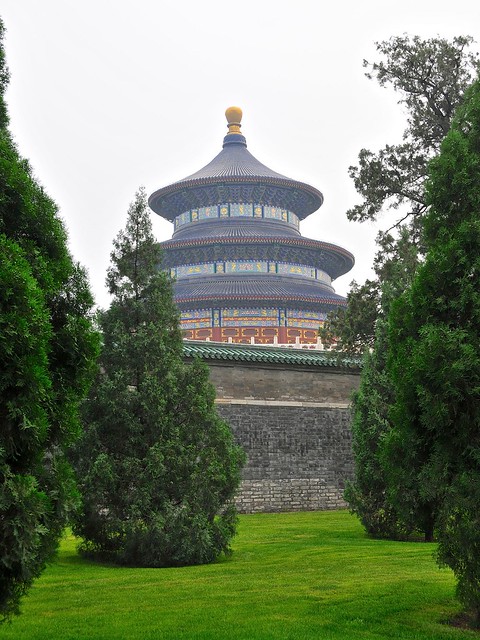

Temple of Heaven

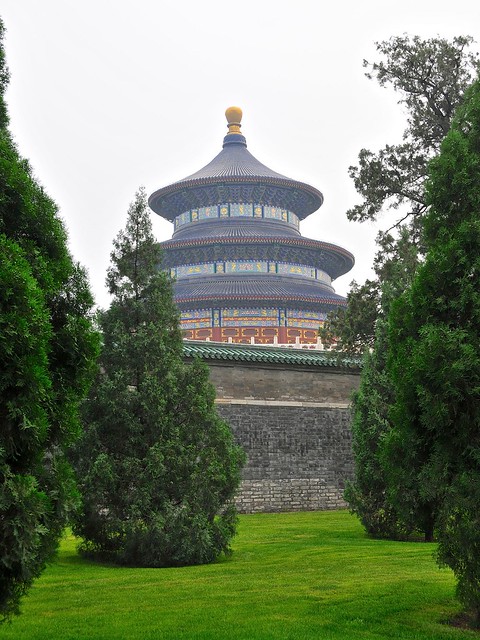

The

Temple of Heaven is everything you might hope a Chinese tourist sight to be: beautiful buildings in a gorgeous setting; not too crowded; not too tacky; and, most of all, occupying a space used by average Chinese people as part of their everyday life.

The temple buildings are set in a huge green park with lush lawns and trees, with lots of courtyards, pavilions, porticos, and spaces for locals to congregate. For some reason it gets only a fraction of the tourists that the Forbidden City does, even though I found it much more pleasant and attractive than the Forbidden City—perhaps its location somewhat further south than most Beijing attractions has something to do with this.

|

| The Temple of Heaven is much more functional as a public space, and is used by locals as such. This sort of communal gathering and socializing in parks is quintessentially Chinese. |

|

| Playing cards and games. |

|

| The central Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests. |

|

| Door detail. |

|

| Music lessons in pagoda. |

|

| Not many people visit the Temple of Abstinence, or Zhaigong. |

|

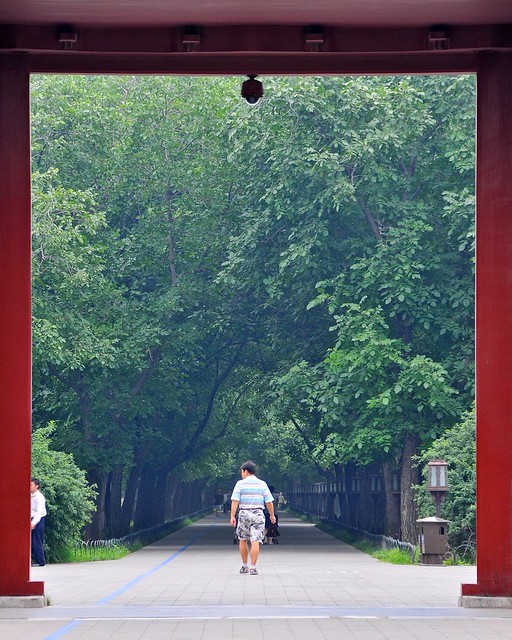

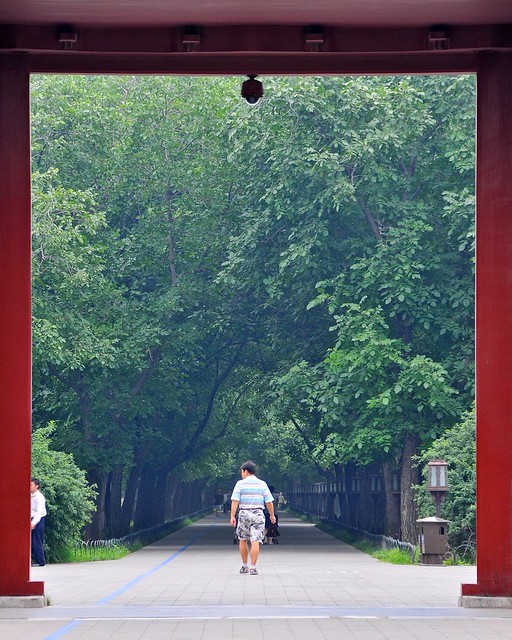

| Gateway from the temple buildings to the surrounding park. |

No comments:

Post a Comment