Even though it was a sleeper bus, we arrived in Hotan before midnight. Although there were no hostels in Hotan, there were a few places that were supposed to be reasonably cheap, one of which was the Transport Hotel (most bus stations have attached hotels). They wouldn't sell me a room for less than 160 yuan, however. I then set out for the other cheapish hotel listed for Hotan, but the horrible maps and terrible directions for Hotan meant it took me about an hour to find where the hotel was supposed to be, only to discover from a security guard that it wasn't there. After a couple of hours of looking for cheap places that could accept foreigners, I ended up sleeping out in front of the bus station—next to the snack vendors also sleeping beside their stalls—for a couple of hours that night, and checking my bag at the station's bag storage in the morning.

|

| Breakfast was a bowl of polo—rice pilaf—with carrots (but without any mutton) from a street vendor. Cost: 4 yuan. |

|

| Big wok of polo. |

|

| Mao shakes the hand of Kurban Tulum, a grateful Uygher farmer who traveled a long way by donkey cart to bring him some local fruit. Thanks, Mao! Kurban is seen by many Uyghur as an Uncle Tom figure. |

|

| The Hotan museum had been closed for a while, but had recently reopened when I was there. It's an older museum & building, but it's still pretty decent and has a couple of mummies as its highlights. |

|

| This one is really well preserved, and much more Han looking than the more famous ones—like the Loulan Beauty—in Urumqi. Perhaps that's why they allow photography here, and not in Urumqi? |

|

| A small mosque decorated with ornate geometric bricks. |

I really hate Lonely Planet sometimes

Other than the museum, the major sights in Hotan are the river and jade market, the carpet factory, the silk factory, and the tomb of the four imams. Lonely Planet's instructions on how to get there are deeply problematic, however. For the carpet factory, which it describes as being on the east bank of the river, it simply says to take bus 10 and get off at the last stop. The problem is that bus 10's final stop is, in reality, a few blocks short of the river, and about 1.5 km from the carpet workshop (which isn't actually on the banks of the river).

I found the river by simply wandering around from where bus 10 turned around, figuring that since we hadn't crossed a river we might if we had continued in the same direction. Once there, I found the location of the carpet workshop by asking at the police checkpoint near the jade market, where I was directed onto the correct road. But since LP said the workshop was on the banks of the river, I kept looking on the side of the road closest to the river, when in fact the workshop is on the side of the road away from the river. Sheesh.

And forget about getting to the silk workshop or the tomb of the four imams from the LP instructions, as they claimed that the silk factory was in the town of Jiyaxiang, "southeast of Hotan," and that the tomb of the imams was beyond Jiya. In reality, all three of these places are northeast of Hotan and the carpet factory. Now, I've seen Michael Kohn get left and right mixed up, and east and west, but getting north and south confused is pretty inexcusable. he probably doesn't care too much, though, because his advice on how to get to these places was limited to taking taxis, even though they're all accessible by public transport, as I later learned.

|

| The White Jade river flows north into the desert. It's fed by melt-water from the Kunlun mountains on the edge of the Tibetan plateau, and only flows in the summer. North of the city if joins with the Black Jade river to form the Hotan river, which flows across the Taklamakan to where it joins the Tarim river. |

|

| Uyghur family on motorbike. |

|

| Horse-bus and trike crossing the river. Despite being very traditional, men and women don't seem to have much difficulty sitting next to one another. |

|

| Progress! A trike bus. |

|

| Every year the melting water and ice dislodge jade from the mountains

and sweep it down the river, which is why these are known as jade

rivers. Searching the riverbed for jade is a popular pastime, and can make people very rich, since the finest white 'mutton-fat' jade is costlier than gold. |

|

| Rows of vendors tables line the waterfront road, with jade stores on the opposite side of the street. |

|

| Stones on display outside the stores, with costlier stones obviously located inside. They all look the same to me. |

|

| A beautiful monochrome carpet in progress. |

|

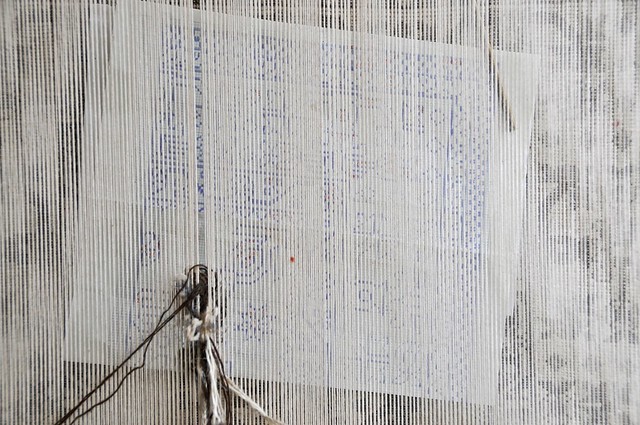

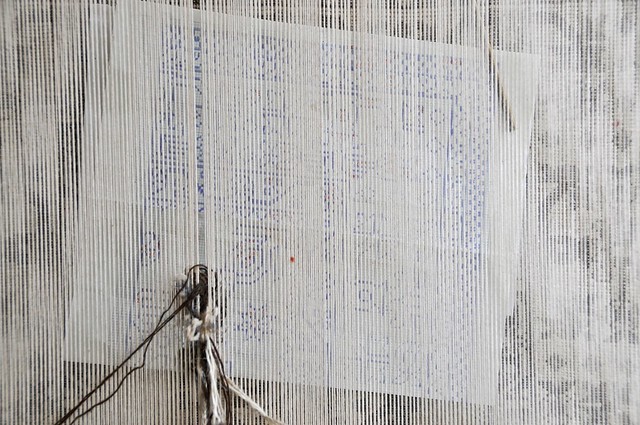

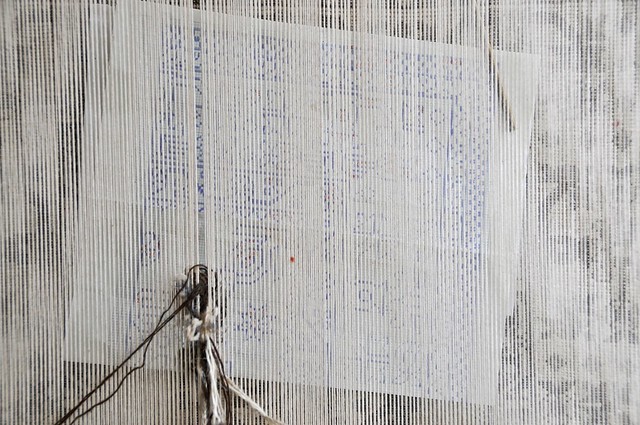

| A carpet in progress, with the yarn stored for tomorrow.You can faintly see the pattern on a piece of paper behind the white warp yarns. |

|

| There were only a couple of workers at the factory when I was there, though it may have been on their lunch break. |

|

| You can see the pattern pretty clearly through the warp in this picture. |

|

| You often have three or four women working on a carpet at the same time. |

|

| Tools of the trade. To the right of the shears is a heavy iron comb that is used to tamp down newly-tied knots to make sure they're snug up to the older knots. This is done after a row has been completed and new weft threads have been inserted. Every few rows the shears are used to trim the newly-made knots, which are of different lengths, to make sure the pile is a consistent length. More info here. |

|

| This tool is used while knotting. This silver needle poking out to right has a hook at the end, and it's used to pick out the warp yarns that the knot will be tied around. The knot is quickly tied and then cut with the blade. All of this happens extremely quickly, almost in a blur, and despite this it can take months for multiple weavers to finish a single carpet. |

|

| Having given up on finding the silk factory, I head back into town, passing these cool dudes who wanted their picture taken. |

|

| The Hotan market is often praised for its authenticity. Here's a meat vendor, and my powers of deduction lead me to believe he's selling camel meat. For some reason the feet don't seem to be used for anything. |

|

| Balloons! |

|

| Mother in full-black robe and veil shopping with her kids. Hotan is probably the most conservative place I saw. |

Marco's Dream Cafe: your source for everything about Hotan

After returning to town, I stopped by Marco's Dream Cafe, which wasn't open earlier in the day. It's run by an ethnic Chinese woman from Malaysia who speaks excellent English and is very helpful, and who maintains a binder full of travel information with lots of updates contributed by travelers. It's the first place anyone visiting Hotan should visit.

We talked about a lot of things, including the development in Hotan. Hotan was long considered one of the poorest cities in China, but the recent

jade boom had transformed the city's reputation and brought in a lot of speculators. Right across from Marco's a new apartment tower was being constructed, and apparently it was a luxury apartment block that was already almost entirely sold out despite the apartments costing about $500 USD per square foot (for comparison, apartments in Manhattan typically sell for about $1,000 per square foot). This made about as much sense to her as it did to me, even though she knew someone who had bought two. But her friend was only going to live in one, and keep the other as an investment—similar logic has resulted in apartment blocks throughout China being completely sold, but unoccupied. When the housing bubble reaches a backwater city like Hotan, you have to really question China's housing bubble.

She also told me about some of the problems with recent Han immigrants. Hotan is one of the most Uyghur cities in China, with probably about 90% of the population being Uyghur. Despite this, she said that most long-term Han residents got along with the Uyghur well enough, in part because they accepted Uyghur customs and showed sensitivity: her example being that established Han residents would use a euphemistic word for pork, and wouldn't use the characters or words for 'pig' in their advertisements, menus, or really anywhere in daily life. Newcomers, on the other hand, would brazenly refer to pork and offend their Uyghur neighbours.

When I was there, I also noticed that there was an internet hotspot that belonged to the cafe, but that it was password-protected. I asked if I could get the password, but she said that she couldn't actually give it out, as you are required to have a license (and presumably track who uses your internet) in order to have an open hot-spot—without a license you are presumed responsible for all traffic over your network—and that she couldn't let anyone, including her regular customers, use the internet over her connection.

Anyway, from her binder of information I learned where the Atlas silk workshop was located, and that you can take public transit to get there. I also learned that the same bus that takes you to the silk workshop will take you most of the way to the tomb of the four imams. Although it was getting a little late, I set out to try and make it to the silk workshop.

To get to the silk workshop, take a bus to Jiya, which will be marked only in Chinese with "吉亚乡." You can catch this bus from the East Bus Station, or from just north of the underpass that's just north of the carpet workshop. On the map below, the stops are the carpet workshop, where you can catch the bus to Jiya, the Atlas silk workshop (tell the driver, but also keep an eye out on the right), and the tomb of the four imams (Asim Imam).

|

| Who needs air conditioning? |

|

| This is what I imagined Pakistan or Afghanistan might look like, not China. I love it. |

I made it to the silk workshop, but they were closing up for the day when I got there, so I only got a brief look before I had to turn around and go back to the city.

|

| Little naked boy with some money on his way to a shop. |

|

| China telecom is everywhere. |

|

| On the bus. |

|

| This swing as set up every day and the guys operating it would charge a couple of yuan to use it for a while. It was really popular. But check out the outfits: I certainly didn't expect to see Shalwar Kameez in China. |

|

| On the side-street next to the swing: a scene that looks like it could be out of Saudi or somewhere. Hennaed hands and only a slit for her eyes, but talking on her cell phone with a coulourful handbag. |

|

| Xinjiang confounds expectations in the most amazing and delightful ways. |

I wonder how people dress now, in late 2014. Apparently the government is cracking down on 'extremist' dress, including beards, veils, headscarves, crescent and star designs, and the like.

|

| The five types of inappropriate dress, now banned. |

The translation of the above sign, according to

The Nanfang, is:

The Five Types of Abnormal Dress

Burqas

Note: It is forbidden for women of any age to wear burqas.

Hijab

Note: It is forbidden for youths, and young and middle-aged women to wear the hijab.

Face Veils

Note: It is forbidden for females of any age to wear a face veil.

Young Adults with Long Beards

Note: It is forbidden for young adults to grow long beards.

Crescent Moon and Stars

Note: It is forbidden for anyone to wear clothing featuring the crescent moon and stars.

That's really unfortunate, and unlikely to win the government any friends in places where such dress is extremely common, especially since one of the stated goals of the policy is "to facilitate better cooperation between ethnic groups."

Although I didn't see any burqas in Xinjiang, I did see a few women with solid scarves over their faces: although you couldn't even see their eyes (you usually can through the window-grid of a burqa), they were able to see out through their finely-woven scarf. I imagine you see even less of this now.

Bus to Kashgar & police checkpoints

I hopped on the night bus to Kashgar and slept pretty well—not unexpected given my station-front sleep the night before. Or I would have slept well, had we not been interrupted twice by what I had come to accept as a frequent annoyance of Xinjiang travel: the police checkpoint. At these checkpoints everyone had to get off the bus and proceed through a customs & immigration-like screening, with ID cards being scanned and checked. Some of them didn't know what to do with me and my foreign and unscannable passport, some made photocopies, and some simply waved me through. At this checkpoint there was a young Uyghur officer on duty, but he seemed not to take things too seriously, with his police hat on sideways and lax attitude. I wonder how being a police officer goes over with other Uyghur, and whether his attitude has anything to do with it.

The other interesting aspect of Xiniang travel is that as frequent as highway checkpoints are, there were even more frequent license-plate cameras. We would be going through the middle of nowhere, when all of a sudden the bus would slow down, a flash would go off and our picture would be taken, then we we speed up again and be on our way. They sure like to know where everyone is, and what everyone is doing. Xinjiang is also the only province where bus passengers had to pass through metal detectors and TSA-style security, with things like cigarette lighters being confiscated.

Budget

August 23 in Hotan: 195

- Bus to Kashgar: 115 yuan

- Left luggage: 6 yuan

- Rice & carrot polo: 4 yuan

- Midnight snacks in front of station: 7 yuan

- Drinks: 24 yuan

- City buses: 9 yuan

- Drink at Marco's cafe: 9 yuan

- Fruit: 17 yuan

No comments:

Post a Comment