After being in Mongolia, I had learned the importance of getting a jump on things if you want to plan on booking a cheap tour or sharing expenses, so I had two early priorities in Kashgar: one, to figure out how much time I had left on my visa, and if I was limited to 30 days since my last entry (most Chinese visas stipulate that you are only allowed to stay for 30 days, and if you want to stay longer you need an extension, while my visa didn't specify a length of stay limitation); and two, how much it would cost to enter Kyrgyzstan via the Torugart Pass (which requires both a permit and private transportation on both sides of the border) and Irkeshtam Pass.

Thus, after checking into the Pamir Hostel, I made my way to John's Cafe. The Uyghur operators there were pretty helpful, but said that it would cost $400 if you did the Torugart Pass solo, dropping to $150 if you shared with three or more people. This was more than I wanted to spend, so the next step was to find out how much the international bus to Osh would cost and when it left. I went to the international bus station, but the lineups were incredible, so I figured I would come back at a different time when hopefully it would be less busy (it's always busy, from what I can tell, and talking to someone would involve waiting for hours).

I then made it to Kashgar's PSB (public security bureau) office to enquire about my visa status. Althoug htey weren't open to actually do any processing, I managed to get the officer working there to take a look at my visa and let me know if I needed an extension if I wanted to stay for more than 30 days. He took a look, and said that since it didn't explicitly say I was limited to 30 days per entry, I could stay until the expiration of my visa. This was a relief, but it also came a bit too late, because I had essentially rushed my way through Xinjiang in order to make sure I would be able to exit the country if I had been limited to 30 days—had I knew I had more time in advance, I might have stayed a day or so longer in Tashkuragan and Karakul, as well as possibly spent more time on the edges of the Taklamakan desert.

|

| I saw this young Uyghur couple fighting in public, on a busy street near John's Cafe. This was really the first example of public violence I saw in China, and I stopped and looked to make sure it didn't escalate, taking a picture or two in the hope it would defuse the situation. She started pushing him and then he grabbed her neck, and then I stepped in to take his hand away from her neck. I'm not sure I would have done this in all places, but by now I think I had gotten a good enough idea of China to understand that this wouldn't be tolerated and that nothing would really happen to me for intervening. After the couple had calmed down, I was walking away and a older American approached me and asked if I was the Uyghur guy's friend, which he had somehow thought I was (I guess I can pass for Uyghur in an American's eyes). |

|

| Is this simply a ripe bitter melon? You can eat the flesh around the seeds, but it was nothing special other than how it looked. |

|

| Looking east from the Yingbin Road bridge over the Tuman river; the international bus station is just to the northwest of the bridge. |

|

| Modern Uyghur family, walking south over the bridge. |

|

| One of my first glimpses of the old city, from a major throroughfare below. |

|

| I wasn't sure how accessible the old city would be, since I had read that some places charge admission, so I climbed a tree to get this shot. Locals looked at me like I was crazy. In about 15 minutes I would be just outside that house, talking with kids who lived there. |

|

| Mother and child watching the sunset from their roof. |

|

| Sunset watching is a popular pastime. |

|

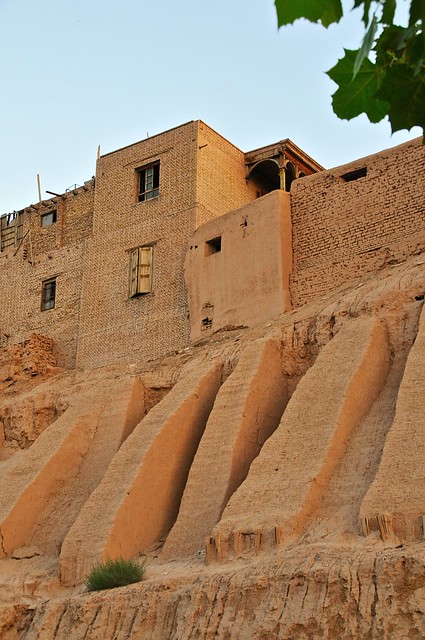

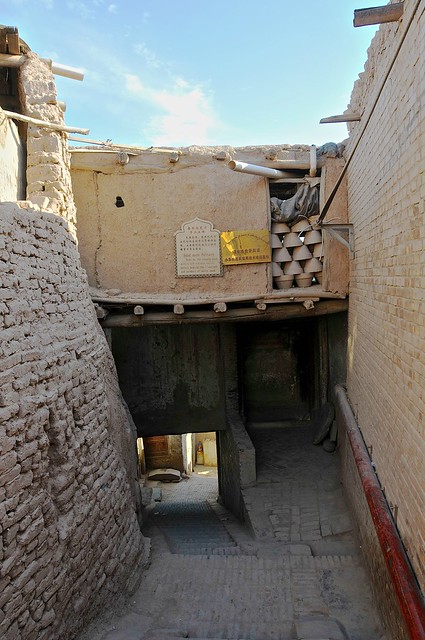

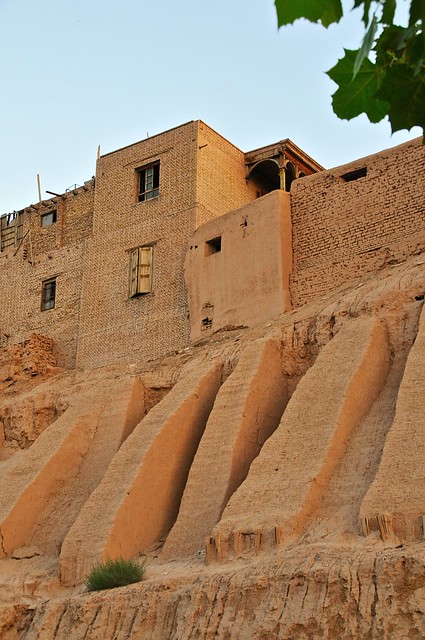

| Interesting foundations and supports shore up the hill. There was a path up the side of the hill, covered with gourd vines. I think I was supposed to pay to enter the area, but there was no one around to collect admission. |

|

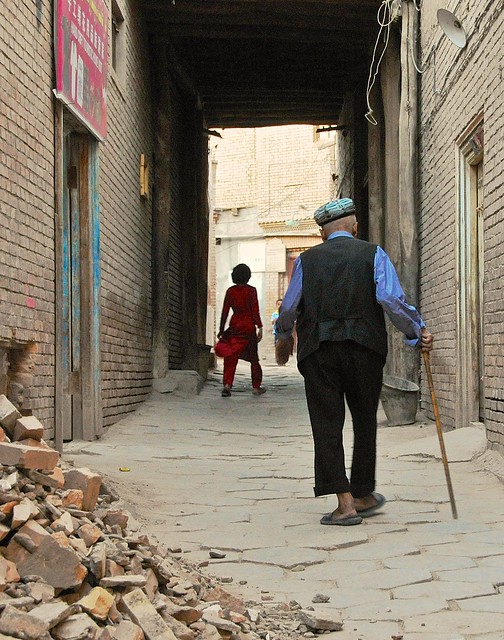

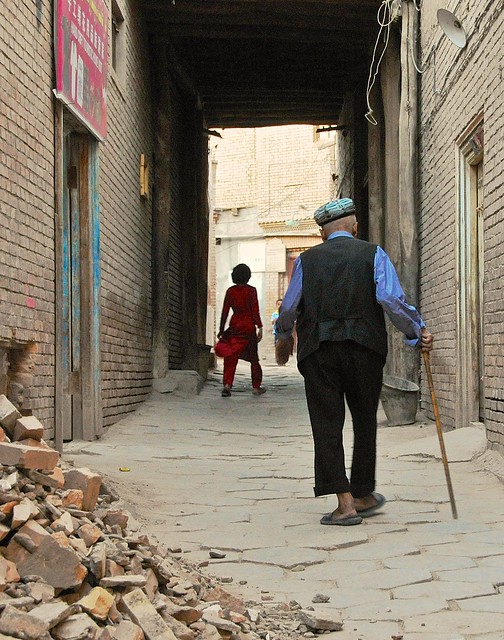

| I had been worried about the well-publicized Chinese policy of destroying the old city, and I had wondered how much would be left when I got there. Well, there was rubble and signs of destruction everywhere. |

|

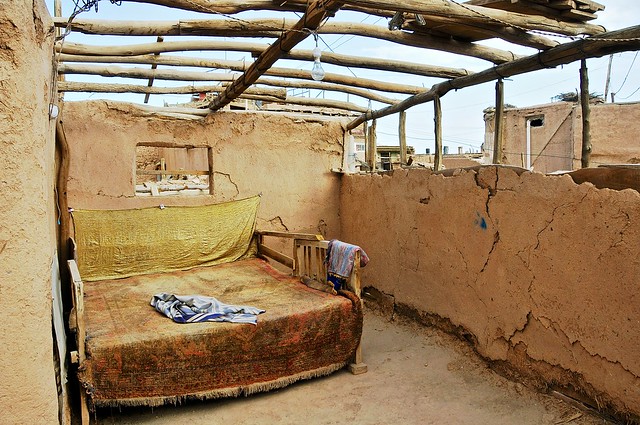

| And yet life carried on, with occupied houses sitting next to bulldozed rubble. |

|

| Destroyed houses line the streets. |

|

| Rubble reaches to the upper halves of doorways. |

|

| From the edge of the old city, in a bulldozed lot, with views of what the future of Kashgar looks like. |

|

| Destruction all around. |

|

| Living amidst ruins. Judging by the brickwork, this house is relatively new, and may be why it was spared: the official Chinese reason for the destruction is to improve building safety in light of the threat of earthquakes. |

|

| A stove sits amidst the ruin. |

|

| Scrambling up the ruins to the second floor. |

|

| In some ways it looks like pictures of post-war European destruction. |

|

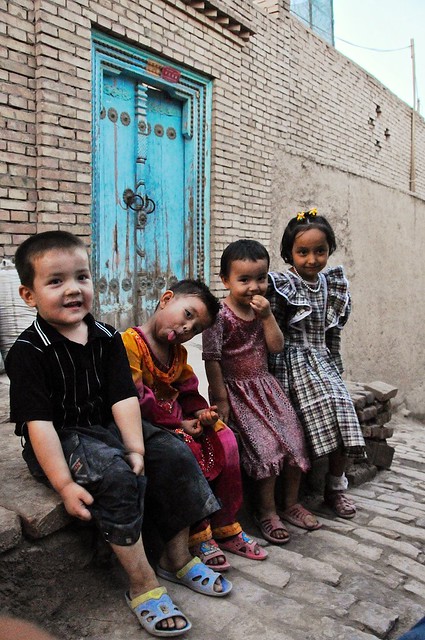

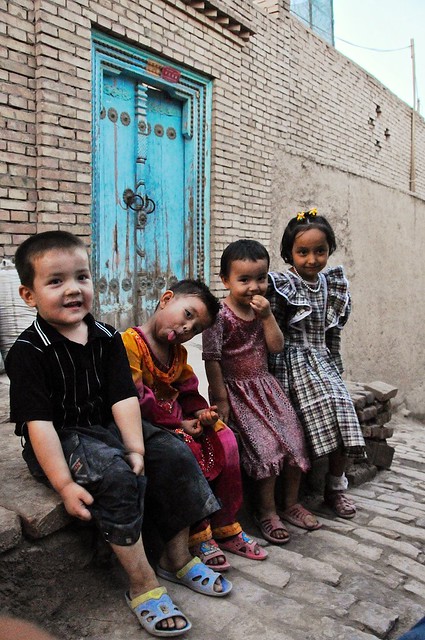

| The house I photographed from below, where I ran into these Uyghur kids (or, more literally, they ran into me). |

|

| They were really funny, and could pose almost as well as Han kids. So friendly, in a way that Han simply weren't. |

|

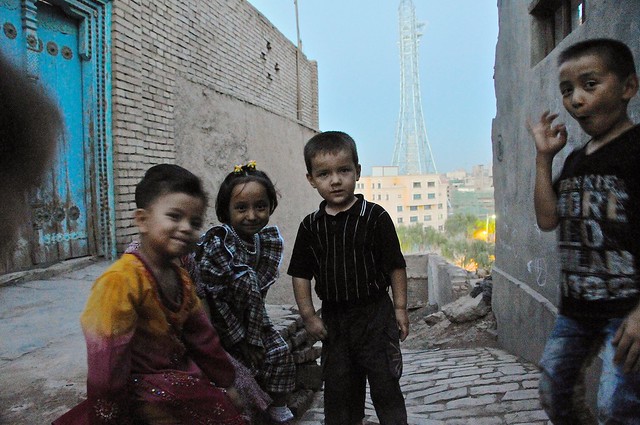

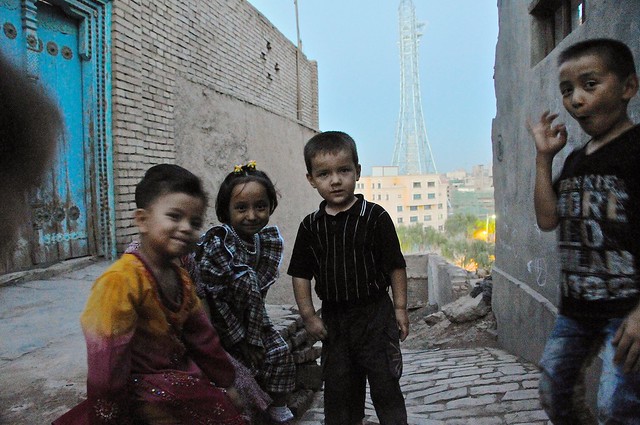

| They all wanted to take turns in front of the tower. |

|

| Note the building on the right had a modern concrete wall, and must have been destroyed and rebuilt recently. |

|

| Frankie Morello's 1999 collection: big in Kashgar. |

|

| Outside their entrance. |

|

| Hennaed hands. |

|

| Goofing off. |

|

| Striking a pose. |

|

| I let the kids use my camera and have some fun, and they enjoyed taking pictures of each other. |

|

| As the sun was setting their mom came out and told me I should leave, so I started heading back down and towards Id Kah. |

|

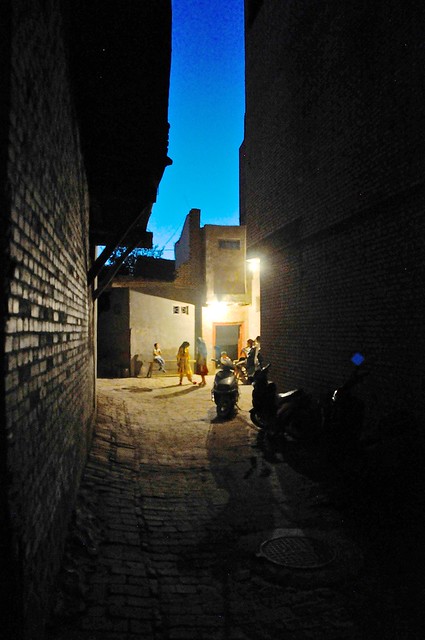

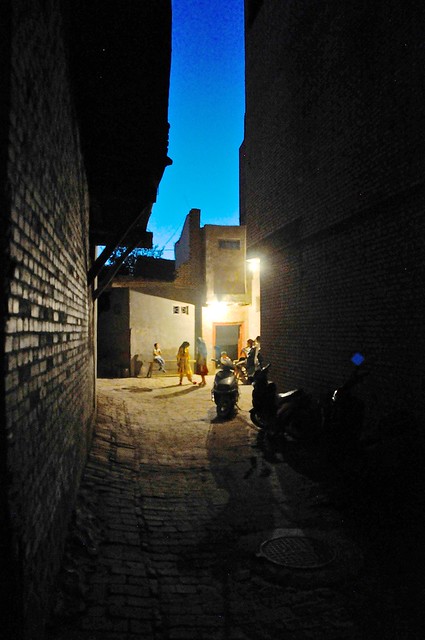

| Socializing in the twilight. |

|

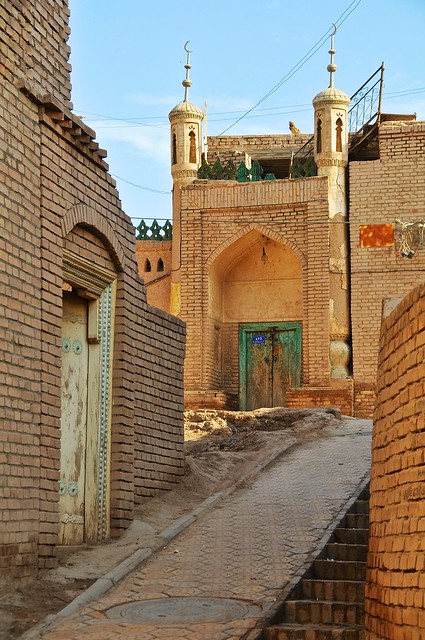

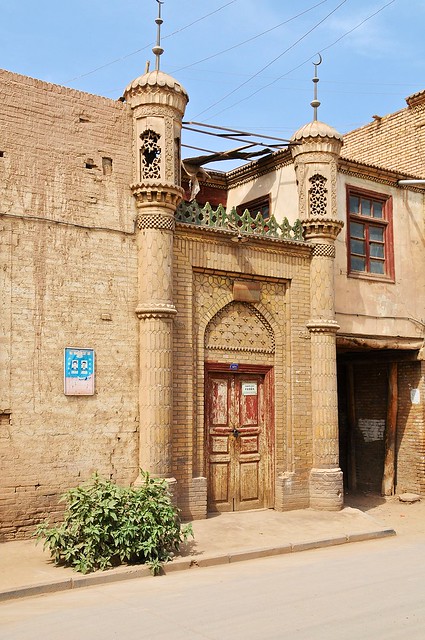

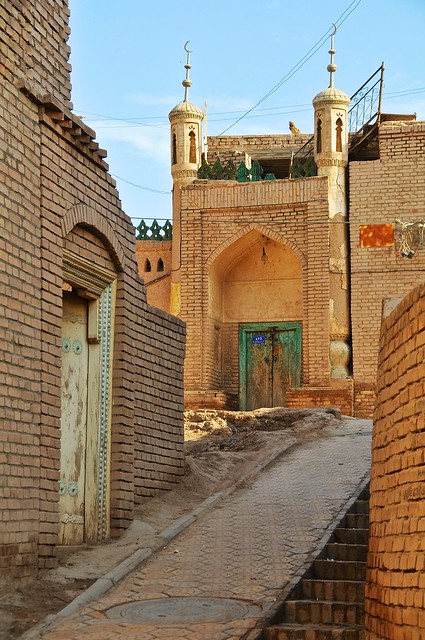

| I had to crouch on the ground with my little tripod to get this shot of a small mosque, as it was really dark. I ended up scaring some girl, who came out of her house on the left and then screamed really loudly when she saw me all huddled up on the ground around my camera and mini tripod. |

|

| I went to a restaurant at the edge of the old town residential section, where it meets the night market. I put my camera on the table and the curious waiter asked if he could borrow it. I showed him how to use it and the took it around, and back into the kitchen, where he took this. |

|

| The waitress in pink didn't want to be photographed, but he was persistent. |

|

| Outside, in the night market. |

|

| On the back of that moto are the Frankie-Morello boy and his sister, the hennaed girl; they shouted and waved as they passed. |

|

| The night market, with strange kebabs, stuffed intestines, goat-head soups, and much, much more. |

|

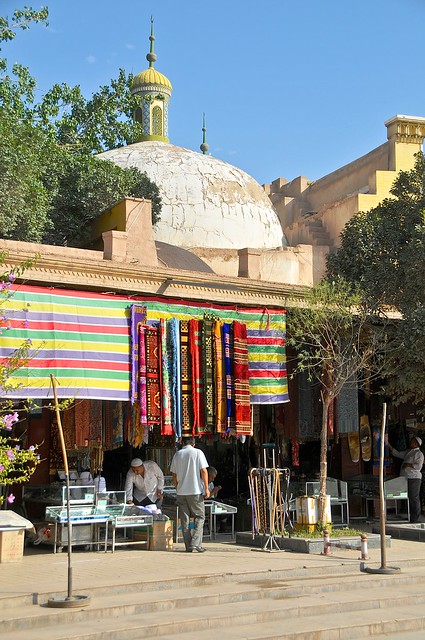

| The Id Kah mosque looks fairly small from the outside, but the inner courtyard and prayer are is quite large. |

|

| The Pamir Hostel is just to the right of this plaza, which can fill with 40,000 or more people on holy days. |

The Pamir Hostel is on the top floor of a modern shopping building to the north of the Id Kah mosque. They have a variety of rooms, with the cheapest being simple dorms, slightly more expensive ones with bathrooms, and more expensive ones with air conditioning. At the end of August it was hot enough that lots of people were sleeping outside or on the roof, but I elected to stay inside (if you can get a room on the north side, they will be cooler). The rooms with bathrooms aren't worth it, as they are dirty like Chinese bathrooms tend to be, and offer little privacy since they don't have proper walls but simply tin and glass partitions: I used the communal bathrooms despite having a bathroom in my room.

They had a couple of new and fast computers with internet access free for guests to use, as well as wi-fi.

Like most hostel in Xinjiang, it's run by young Han. These Han actually seemed very respectful of Uyghur customs, and the girl who seemed to be in charge wore a headscarf, but it would still be nice to have more money going to local Uyghur.This is especially the case since the agent at the snack/drinks/news stand between on the corner of the night market opposite Id Kah spoke excellent English and told me that he was a University graduate, but was still working in a little shop. It's a shame that there aren't easier and better ways for tourists to support Uyghurs.

Day two

Although Kashgar is the largest Uyghur city in Xinjiang (Urumqi has always been a Han-dominated city), with a population of around 800,000, the old town has always been a

relatively small area roughly centered on the Id Kah mosque. The area west of the mosque has been pretty heavily modernized, and the surviving pockets of the old town—where even the demolished areas are being rebuilt in traditiona-looking styles—are mainly to the east of the mosque.

|

| West of the mosque, religious buildings are the last to survive.. |

|

| But rebuilding is much more common. I believe this watermelon was protecting passerby from projecting rebar. |

|

| Modern reconstruction is at least attempting to look traditional, instead of Chinese-style multi-story concrete blocks. I like the little tea kettle boiling on the corner. |

|

| Modern materials in a traditional layout. |

|

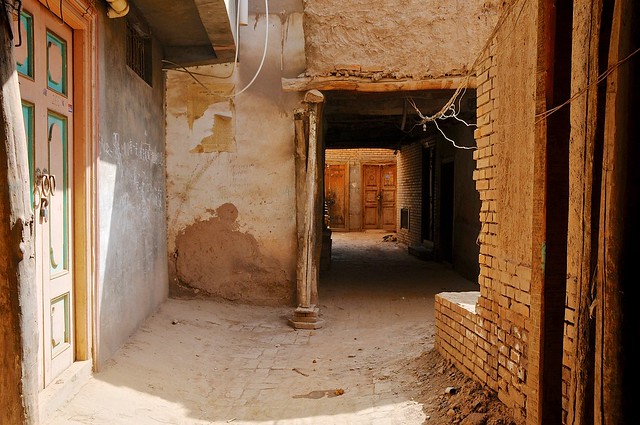

| A pocket of traditional buildings up a blind alley. |

|

| Mud daubing on the walls. |

|

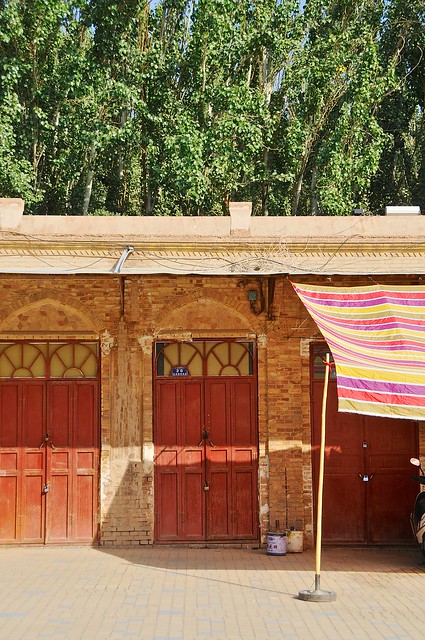

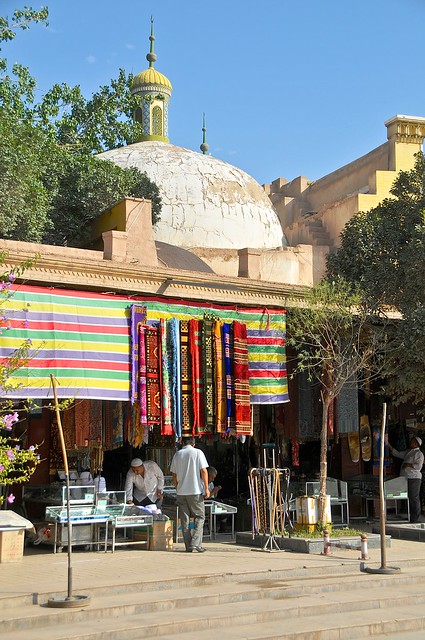

| On the southern wall of the mosque are rows of shops. |

|

| They mainly sell religious garments and artefacts. |

|

| The entrance is relatively unimposing, but the mosque opens up considerably behind the walls: first into a large treed courtyard, with the covered prayer area at the western edge of the courtyard. |

|

| South of the mosque is this new complex of shops and a tower, built in the customary Chinese tradition of pretending to respect local styles by putting lipstick on their modern pigs. |

|

| An attractive building which I took to be either a religious building or the richly decorated home of a prosperous merchant. |

|

| The lone survivor of a destroyed neighborhood. |

|

| Chairman Mao looks over a square with all the personality and charm of Tiananmen—none whatsoever. But unlike Tiananmen, this square is always empty. |

|

| The traditional blacksmith shops on the left used to be adobe and timbered, not the new and ornately tiled buildings you see today. In honesty, I can see it making some sense to modernize storefronts along busy streets, but less sense to modernize residential areas en masse. |

|

| Only shrines survive. |

|

| Modernized blacksmith shop. |

|

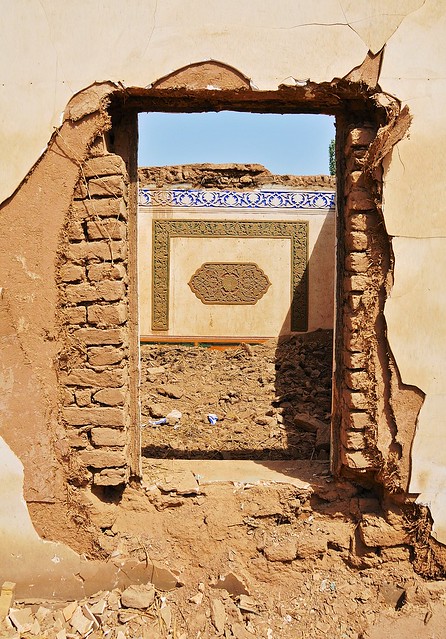

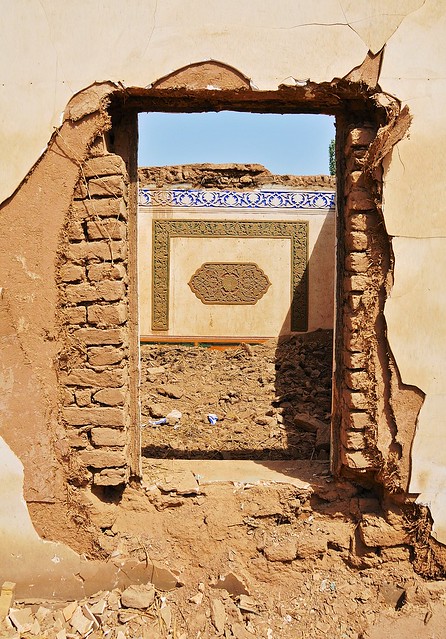

| Richly decorated interior lurk beneath anonymous exteriors, as the rampant demolition reveals. |

|

| Typical Uyghur woman in front of a shrine. |

|

| Bulldozers in the old city keep up the destruction even on Sundays. I wonder if they do so on Fridays, the Muslim holy day, too. |

|

| I think they sell watermelons here. |

|

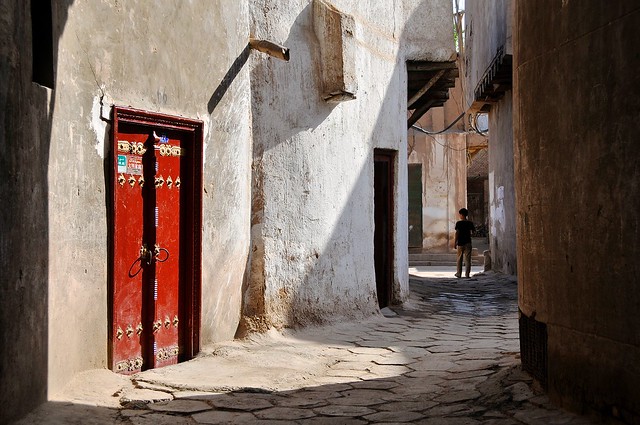

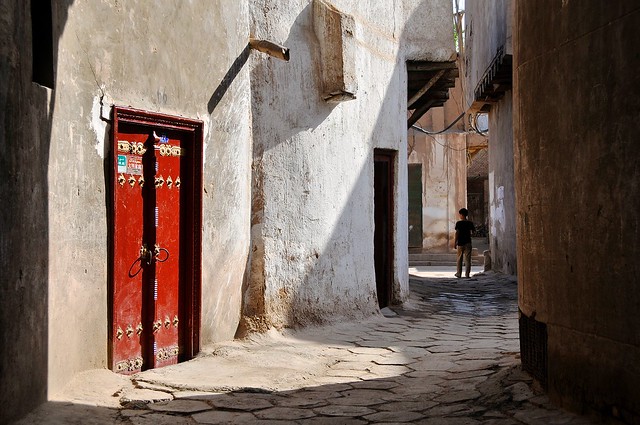

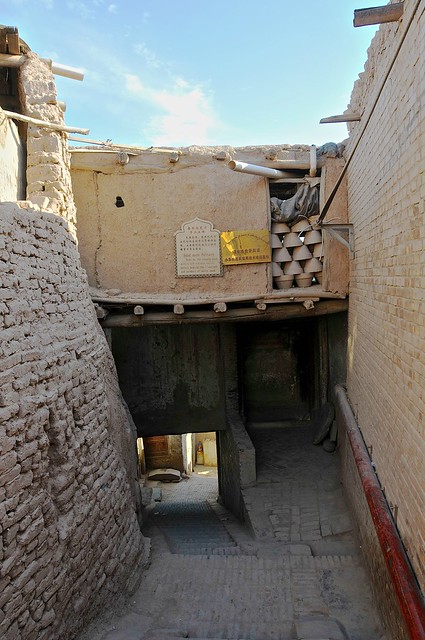

| There are only a few streets capable of allowing car traffic in the old city, and side streets off of them typically look like this. |

|

| Market along a dusty main street. With the ongoing demolition an increasing number of streets are being widened and opened up to car traffic. |

|

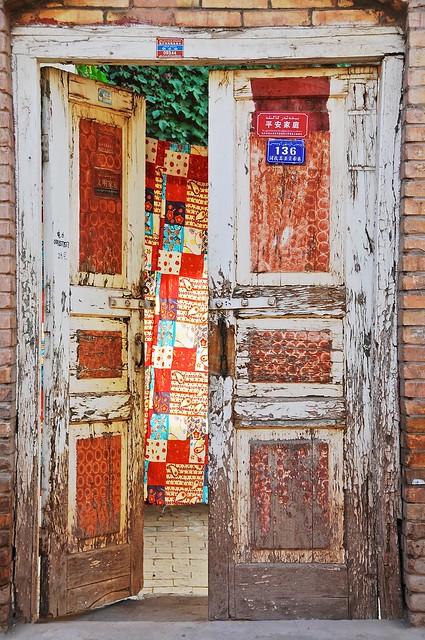

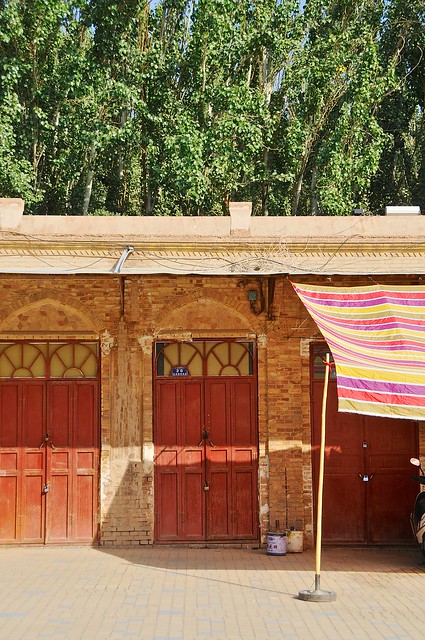

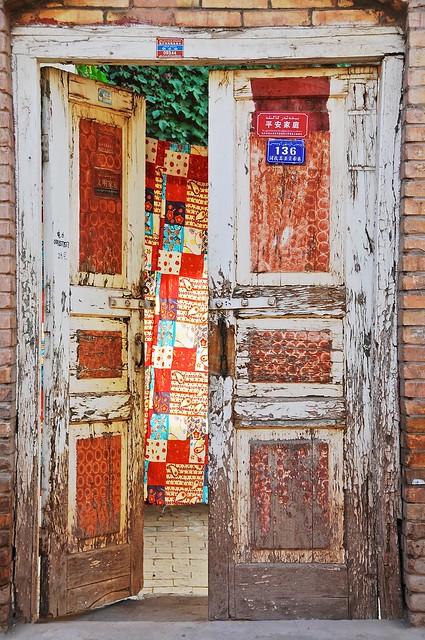

| Construction keeps up with the destruction. The recycling of old doors and windows will help mask the fact that buildings are new and the result of destruction. |

|

| This old door will be integrated into a new structure. |

|

| I fear the ornate interior decorations will not be replicated in the replacement buildings. |

|

| The results of older rebuilding efforts betray no sensitivity to local styles. |

Sunday Livestock Market or Mal Bazaar

Kashgar has two famous Sunday markets. The first, the so-called Sunday Market, is actually a huge bazaar that is open every day. The second, the

mal bazaar or livestock market on the outskirts of Kashgar, actually only happens on Sundays.

The livestock market has been relocated since I visited, but when I was there you could catch a (crowded) city bus from near the international bus station.

|

| Uyghur man and grandson ride their donkey cart full of onions into the city near the bus station. |

|

| Roadside trees near the Mal Bazaar were a popular place to rest. |

|

| Six days a week the livestock market is just a big, empty parking lot. On Sundays it turns into a huge collection of sheep, goats, cows, the odd yak and camel, food and drink vendors, and the people who want to buy them. |

|

| Vendors selling what looks to be kvass—which is mildly alcoholic—in this dusty market. I wonder if it isn't something else, given the attire of those buying and selling it. Given the proximity of livestock, even I would be a little worried about hygiene. |

|

| Fat-tail sheep are the only variety you are likely to see in Central Asia. Their asses bounce around in ways that would make Kim Kardashian jealous. All across Central Asia the fat is the prized part of the sheep, and so just about any dish made with mutton is likely to contain much more fat than Westerners are accustomed to. On kebabs and shahlyk, you usually have alternating chunks of meat and fat. They also sell kebabs that are only fat: don't make the mistake of seeing they are white and thinking they are chicken kebabs. In samsas, the fat content seems to vary between 20% and 60—and usually on the high end, which makes them pretty unpalatable to me. |

|

| Some sheep are trimmed, while some have full coats. You will see some vendors using small scissors to trim and sculpt the wool on their animals' asses. My personal idea is that those that are trimmed are emphasizing how fat the tails are, and are sold for consumption, while those that are untrimmed are sold to be kept as livestock. |

|

| Old man and his sheep. |

|

| Sheep and goats are tied up head-to-head in long lines, but take it all in stride. |

|

| Rows of livestock. |

|

| That's a lot of sheep. |

|

| Checking out the merchandise. |

|

| I have no idea where they got that yellow tape from, but I like it. |

|

| The cattle section was pretty small. |

|

| Other than those long lines of tied-up livestock, I have a hard time telling who is selling and who has just bought. |

|

| Big buyer, or just a late-arriving seller? |

|

| She's carrying a sheep in her arms. |

|

| Om nom nom. |

|

| Interesting headgear on this old Uyghur. |

|

| Trimming their sheep. Ass touchups will come later. |

|

| Midday prayer at the edge of the market, near the toilets. |

|

| A recalcitrant yak being led to his new owner's truck. |

|

| This camel wasn't too happy to be there, and was being sold because of a leg injury he had. |

|

| Seeds and spices for sale, with a refreshment cart behind. |

|

| Sharpening a knife on a hand-powered whetstone. |

|

| Making sure the sheep are happy and well-fed. Maybe they're not for slaughter, then, but merely for presentation? |

|

| They can carry up to 20% of their weight in their ass. |

|

| Bringing home the mutton. |

|

| How many sheep can you fit in a microvan? Quite a few. |

|

| Some sheep are immediately slaughtered. |

|

| Selling the intestines and offal. |

|

| Old Uyghur man and his new sheep. |

|

| Donkey carts leaving the market. |

|

| Poplar-lined road just north of the market, while waiting for the bus back to town. |

|

| Fields and mountains to the north. |

Sunday Market

Kashgar's Sunday Market is actually open every day, and is supposedly the largest bazaar in the world. It's certainly very big, but even after visiting I had figured that this must be hyperbole and that places like Istanbul's Grand Bazaar must be bigger. Well, the tourist trap known as Istanbul's Grand Bazaar certainly isn't bigger—though I suspect that Tehran's Grand Bazaar could give it a run for the money—but Kashgar's Sunday Market remains a little disappointing if only because the buildings are modern and perhaps too well organized to capture the traveler's imagination. The market is divided into different departments, with each block of the market dedicated to a specific category, from blankets to silk fabric, to shoes, to electrical accessories, to hardware, to paint, and so on and so forth. This leads to a bit of monotony for the sight-seer, even if it is convenient to people who are actually shopping.

As a shopper, the biggest inconvenience is that all of the shops seem to sell the exact same thing. So while there may be over one hundred shops selling men's clothes, they all seem to carry the same fashions and styled. If you want a sweater with the Apple logo and the word "iPhone" emblazoned on it, you can get it at a hundred shops. If you want a pair of 100% cotton, khaki coloured pants, or a simply cotton button-front shirt, you will find zero shops that offer it. It's pretty much the same story throughout Central Asia: hundreds of shops, all selling the same goods... or at least that's how it seemed to me.

|

| Women's textile and trim section. |

|

| Cheap, machine-made carpets. |

|

| Cotton fabrics. |

|

| Silks. |

|

| Synthetic blankets. |

|

| Ikat, or Atlas, silks. |

|

| Spices and dried foods. |

|

| Carpets and rugs. |

|

| Cool and refreshing dogh—shaved ice, yoghurt, and sweet syrup that is mixed by pulling it in a bowl. I got it from a hugely popular stand outside the market, on the banks of the Tuman river. You can see how they prepare it in the video below. |

|

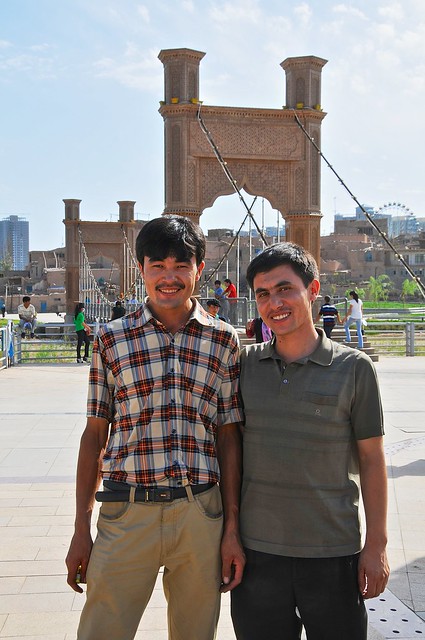

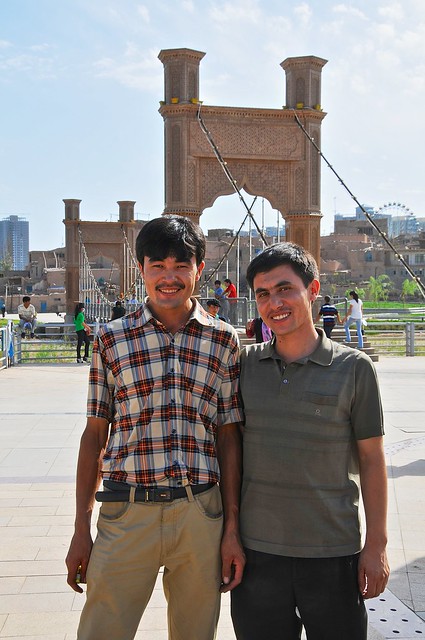

| As I sat drinking my dogh and reading my kindle, I was approached by these two Uyghur guys. They weren't that impressed with the kindle (it's black and white and it only shows text?), but they wanted to trade for my Blundstone boots, even though there was a small tear where the uppers joined the soles (Blundstone Australia, amazingly, ended up sending a replacement pair to me in Kyrgyzstan). They liked my camera more and I let them use it to take some pictures. |

|

| The edge of the Sunday market from across the Tuman river. There's another section of the old town on this side of the bridge. |

|

| This section seems to have escaped destruction thus far. |

|

| Perhaps because it's selling itself as a tourist zone (there's also an amusement park behind it), with plaques describing some buildings and inviting people in to visit various workshops (this one for hand-made pottery), and Uyghurs selling handicrafts in the streets. |

|

| Uyghur kids having fun, with a cute little kitten. |

|

| Hats for sale on the left. This kid without pants was unusual, as most Uyghur kids don't have the split pants the Han kids do, nor do they seem to urinate everywhere. |

|

| I let these kids use my camera, too. So long as they wore the neckstrap (my camera and lens was pretty big and heavy, and kids have small hands), I was totally comfortable with letting them run around with it. |

|

| Another picture by one of the Uyghur kids. |

|

| I'm in the background there. |

|

| Showing them my kindle. |

|

| Pretty good picture for a young kid. |

|

| Interesting entrance. |

|

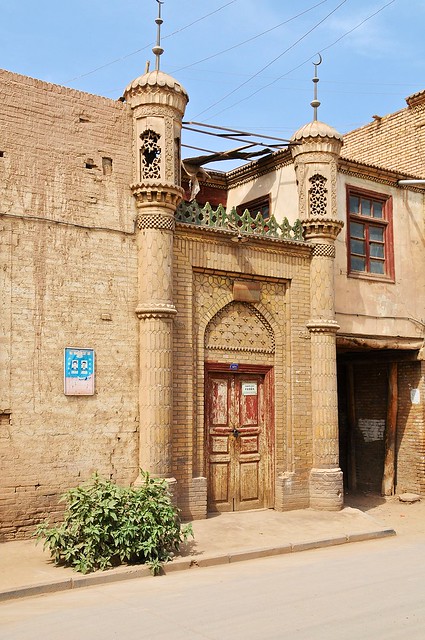

| Small mosque. Apparently the hexagonal street tiles indicate that the street is a through-street, while other shapes indicate it is a dead end. |

|

| Uyghur woman selling handicrafts. |

|

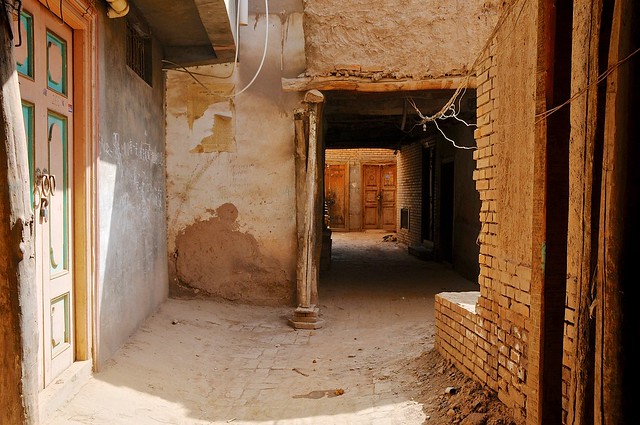

| Much of the character of the old town is due to the inability of cars to navigate it. |

|

| Colourful entranceway. |

|

| But there's some demolition occurring even in this district. |

|

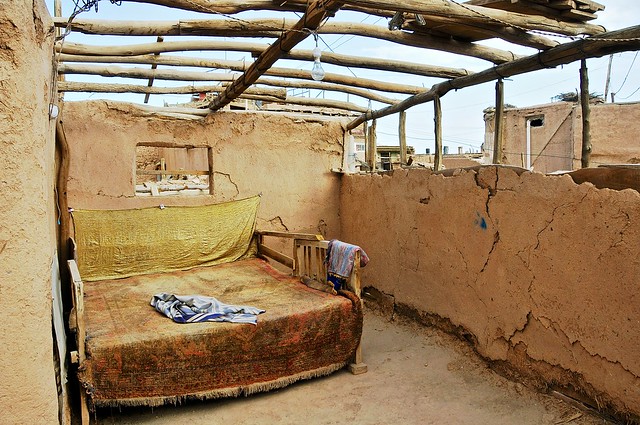

| You'll be invited into some old homes to look around, but there's inevitably some light pressure to buy a souvenir hat or something at the end. I wonder if they don't purposefully make their homes look poorer to generate sympathy (the ornate decoration you see in the interiors of demolished houses suggests that they aren't as poor as they might appear from the outside). |

|

| Goat heads are a common Uyghur offering at night markets. |

|

| Skewers simmer. |

|

| Banpanji—a small serving of Dapanji ("big plate of chicken")—for dinner. |

|

| Melon and naan vendors line the streets next to the night market. |

|

| The typical large naan with baskets of bagel-naan in front. |

Day 3

On the third day I decided to see the tomb of

Afaq Khoja, which has huge religious significance for the Uyghur and

huge propaganda significance for the Chinese government. Whereas the Uyghur have traditionally viewed Khoja as a great Sufi religious leader, for the Han the mausoleum is mainly of interest as the final resting place of the fragrant concubine, whose extraordinary beauty bewitched the Qianlong emperor. This official Chinese narrative fits neatly with the Han exoticism of—and objectification of—Uyghur women, while also emphasizing the long Chinese interest in this far-west outpost.

Interestingly, there has been a recent reinterpretation of Afaq Khoja among the Uyghur as something of a

traitor to the people—a reinterpretation that has been seen by some as a response to Chinese co-opting of him for their own nationalistic purposes.

|

| Melon specialist. |

|

| Produce galore. |

|

| Even buildings outside of the traditional old town are being destroyed, such as this one near the mausoleum for Afaq Khoja. |

|

| There's a mosque next to the mausoleum, with richly decorate pillars. |

|

| An arched and patinated entranceway. |

|

| A Uyghur in the open-air mosque. |

|

| Gorgeous camel for tourist pictures. |

|

| The mausoleum. Inside ore the tombs of Afaq Khoja and many of his descendants. |

|

| Tilework on the exterior. In many places there are clear signs of older, clumsy restorations, and it's difficult to imagine what it originally looked like. |

|

| Many of the tiles are missing. |

|

| There was a small side garden with irrigation ditches, from which this picture was taken. |

|

| Dusty rose bushes in front of the tomb. |

|

| Only a few tiles remained on the dome. I believe the mausoleum has been substantially restored since I was there. |

|

| Richly-decorated interiors gone forever. |

|

| Street-side sunflowers on the way back from the mausoleum. |

|

| Small mosque in the old town. |

|

| Naan-making tools. Rolling pins and small stamps used to emboss the patterns in the middle of the bread. |

|

| Chinese-medicine supplies, from snakes and starfishes to dried frogs. |

|

| I'm not sure if Uyghur have adopted Chinese medicine, but this was in a Uyghur-dominated market. |

Now that I knew I wasn't subject to a 30-day limit on my visa, I had extra time to play with: instead of having to leave by the 30th, I could stay until much later, if I so desired. I decided to take advantage of the extra cushion by re-visiting Hotan to see the silk workshop and Asim Imam tombs. I thus booked a ticket on the night bus to Hotan, left my bag at the hostel, and left for another daytrip to the city.

Budget

August 26: 142 yuan

- Pamir Hostel: 50 yuan

- City bus: 3 yuan

- Drinks: 23 yuan

- Naan: 1 yuan

- Medicine for my still-sore throat: 20 yuan

- Banpanji: 45 yuan

August 27: 156 yuan

- Bus to Hotan (no AC): 85 yuan

- Afaq Khoja ticket: 20 yuan

- Cake and donut: 10 yuan

- Drinks: 21 yuan

- City bus: 2 yuan

- Dinner—suoman: 18 yuan

No comments:

Post a Comment