Shortly before arriving in Kerman, my conversation partner invited me to have breakfast with him. I would have agreed, but I had to find the Canadian couple I was traveling with, as they left the bus ahead of us. When I found them, I couldn't find my Iranian friend, and I felt a bit bad. But maybe the breakfast invitation was just taarof?

Anyway, we took a taxi from the bus station to one of the hotels listed in Lonely Planet. I'm not a taxi person in any culture or country, but I got sucked along with the couple I was traveling with. The small hotel we went to was nice but somewhat basic, and the Canadians were shocked by the price, as it was 270,000 rial for a triple room with a private bathroom, TV, and fridge, as well as a shared kitchen. They thought this was the per-person price, but were surprised it was the price for the room. So, basically it was half the price of Vali's, for much nicer accommodation. In reality, this was the kind of pricing that I saw in most of Iran, as the devaluation really did make most things cost less than half (in dollar terms) of what they would have been earlier in the year.

Anyway, after stowing our bags, freshening up, and making some instant coffee in the kitchen, we headed out towards the main sight in Kerman: the grand bazaar and Ganj Ali Khan complex.

We left the hotel together and walked maybe 50 meters to the main street. As soon as we reached the busy main street, however, I realized something was up. Literally everyone we came across would turn to look at the Canadian couple (both of whom were very white and had sandy-coloured hair), with most of the attention being given to the girl. The males would do a good job of not staring until the passed the couple, but their heads would swivel afterwards, while Iranian girls would openly stare without attempting to conceal it. Within the first five minutes we had been approached in English by at least three people who wanted to talk to us. But when I say we were approached, I really mean that the white guy was approached: it would be improper for these Iranian males to directly address an accompanied female, and I was basically ignored (as I would learn later, the locals probably thought I was an Iranian tour guide or friend who was accompanying them, if they even noticed me at all). It was incredibly surreal to see how different our experiences were, and how much attention was being lavished on these white folks while I passed unnoticed even though all of us identified as Canadian, that I had to laugh. But as surreal as it was to me, the Canadians were totally unfazed, as they had been in the country for a while and were undoubtedly accustomed to all the attention.

We headed down towards the grand bazaar, which was a pretty nice introduction to Iranian covered markets. Unlike in most of Central Asia, in Iran there are lots of mosques, markets, baths, and other buildings that have been in continuous use for hundreds of years. These aren't recently-(over)restored tourist pieces like you see in Uzbekistan, but living and breathing buildings that have been maintained and cared for over the years. Even in places where the Mongols destroyed buildings in the early 13th century, by the first years of the 16th century the Safavid empire overthrew the Timurids in Iran (which was no slouch in the the architecture department, as Samarkand shows), ushering in "modern" Persia and a prolonged era of stability. And as Iran has never been colonized, as most of Central Asia was by the Russians, there has never been a move away from these traditional buildings.

As a result, the bazaars in most Iranian cities continue to be the exact same sort of traditional bazaars that have existed for hundreds of years: mazes of inter-connected alleys with small domes forming the roofs—though these are barely noticeable from inside the markets, as you're not often tempted to look up and admire them amidst the bustle. These bazaars feel both exotic and, after a while, surprisingly commonplace and unremarkable.

Kerman's grand bazaar is located adjacent to the Ganj Ali Khan complex, which contains a large rectangular square surrounded by arched cells (like a madressa), complete with fountains and greenery, and surrounded on the sides with a caravanserai, a mosque, and a hammam (bath).

Anyway, we took a taxi from the bus station to one of the hotels listed in Lonely Planet. I'm not a taxi person in any culture or country, but I got sucked along with the couple I was traveling with. The small hotel we went to was nice but somewhat basic, and the Canadians were shocked by the price, as it was 270,000 rial for a triple room with a private bathroom, TV, and fridge, as well as a shared kitchen. They thought this was the per-person price, but were surprised it was the price for the room. So, basically it was half the price of Vali's, for much nicer accommodation. In reality, this was the kind of pricing that I saw in most of Iran, as the devaluation really did make most things cost less than half (in dollar terms) of what they would have been earlier in the year.

Anyway, after stowing our bags, freshening up, and making some instant coffee in the kitchen, we headed out towards the main sight in Kerman: the grand bazaar and Ganj Ali Khan complex.

We left the hotel together and walked maybe 50 meters to the main street. As soon as we reached the busy main street, however, I realized something was up. Literally everyone we came across would turn to look at the Canadian couple (both of whom were very white and had sandy-coloured hair), with most of the attention being given to the girl. The males would do a good job of not staring until the passed the couple, but their heads would swivel afterwards, while Iranian girls would openly stare without attempting to conceal it. Within the first five minutes we had been approached in English by at least three people who wanted to talk to us. But when I say we were approached, I really mean that the white guy was approached: it would be improper for these Iranian males to directly address an accompanied female, and I was basically ignored (as I would learn later, the locals probably thought I was an Iranian tour guide or friend who was accompanying them, if they even noticed me at all). It was incredibly surreal to see how different our experiences were, and how much attention was being lavished on these white folks while I passed unnoticed even though all of us identified as Canadian, that I had to laugh. But as surreal as it was to me, the Canadians were totally unfazed, as they had been in the country for a while and were undoubtedly accustomed to all the attention.

We headed down towards the grand bazaar, which was a pretty nice introduction to Iranian covered markets. Unlike in most of Central Asia, in Iran there are lots of mosques, markets, baths, and other buildings that have been in continuous use for hundreds of years. These aren't recently-(over)restored tourist pieces like you see in Uzbekistan, but living and breathing buildings that have been maintained and cared for over the years. Even in places where the Mongols destroyed buildings in the early 13th century, by the first years of the 16th century the Safavid empire overthrew the Timurids in Iran (which was no slouch in the the architecture department, as Samarkand shows), ushering in "modern" Persia and a prolonged era of stability. And as Iran has never been colonized, as most of Central Asia was by the Russians, there has never been a move away from these traditional buildings.

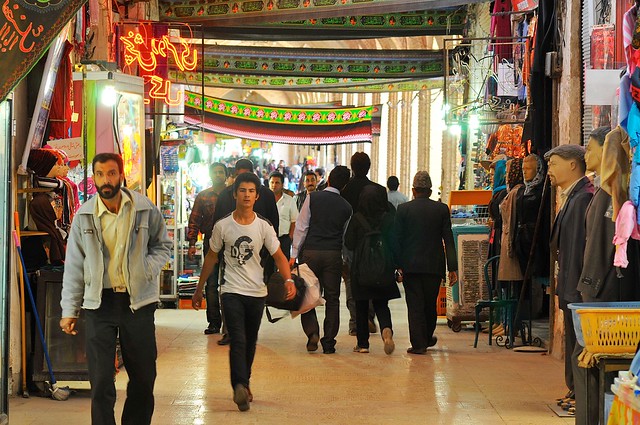

As a result, the bazaars in most Iranian cities continue to be the exact same sort of traditional bazaars that have existed for hundreds of years: mazes of inter-connected alleys with small domes forming the roofs—though these are barely noticeable from inside the markets, as you're not often tempted to look up and admire them amidst the bustle. These bazaars feel both exotic and, after a while, surprisingly commonplace and unremarkable.

Kerman's grand bazaar is located adjacent to the Ganj Ali Khan complex, which contains a large rectangular square surrounded by arched cells (like a madressa), complete with fountains and greenery, and surrounded on the sides with a caravanserai, a mosque, and a hammam (bath).

|

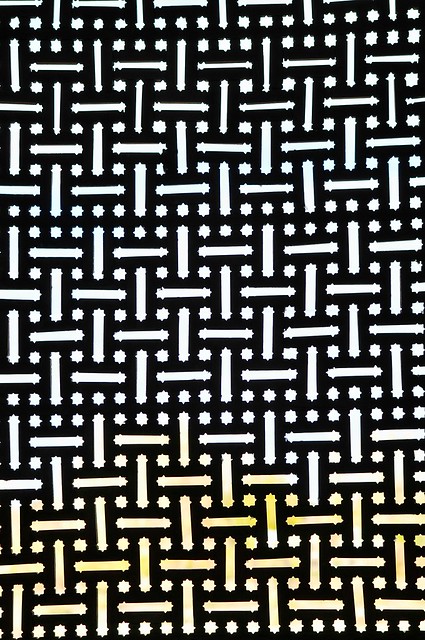

| Pishtaq leading to the caravanserai at the Ganj Ali Khan complex in Kerman, built in the Safavid era between 1591 and 1631. Although the large rectangular square looks like a giant caravanserai, the actual caravanserai is a small square courtyard behind the pishtaq. |

|

| View down the bazaar, which runs along the southern side of the complex. |