Darvaza gas crater: an opportunity missed

More than Merv and Konye Urgench, perhaps the biggest tourist draw in Turkmenistan is the Darvaza gas crater, also known as the Gates of Hell (a particularly apt nickname given that Darvaza translates as "gate"). The crater, which is a giant pit in the ground—some 70 meters across— that just happens to be on fire, was created by gas exploration gone wrong: in 1971 the Soviets drilled into a large cavern just below the surface, causing the ground to collapse into the crater we currently see. As noxious gas was escaping from the crater, they decided to flame off the fumes, expecting that it would soon burn itself out. Except it hasn't, and the crater has continued to burn ever since.It turns out that the gas crater is less than 5km east of the highway between Ashgabat and Konye Urgench/Dashogus, and I probably could have seen its glow from the road. Of course, I would have had to know when to look for it, but since I had no idea where we were or even where Darvaza was, this was a bit of a problem. Now, when every cheap smartphone has GPS built in and there are lots of offline maps apps available, it would be much easier to figure these sorts of things out.

If I had more time or better preparation I would have asked to be let off at one of the chaikhanas near Darvaza (we actually stopped at a chaikhana for a brief food and bathroom break, and it's actually possible it was near Darvaza, although I didn't see anything glowing), as it's possible to sleep at a chaikhana and hike out to the crater in the middle of the night to see the flames at night and in the early dawn light (again, GPS-enabled maps of your chaikhana and the crater are pretty essential in order to do this properly), and this would be a great way to see them without adding much extra time to your trip.

Anyway, on we went through the night, and I managed to catch some sleep, until we came to the outskirts of Ashgabat, whereupon the van made a slight detour and dropped off the girls in the front row to their family in a waiting car. We made a few more stops as we entered Ashgabat, until there were only two of us left. I asked to be dropped off at the station, and then the van departed with the remaining passenger. Unfortunately, this means I have no idea where the share-taxi lot is for people leaving Ashgabat, but thankfully it's not information I needed to know since I left the city by train later that evening.

During the drive I spoke briefly with one of the guys sitting next to me. He broke the ice by asking me to put on my shoes because apparently my feet were smelly (likely a sign that Turkmen are more refined than mountain-dwelling Central Asians, as I doubt anyone in Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan would have batted an eye). He had to do this by pantomiming on discovering I didn't speak Turkmen. Of course, my inability to speak Turkmen naturally led to the question of where I was from. But really, he couldn't get over the idea I didn't speak Turkmen, as though it would be natural that a Canadian would speak Turkmen. This was very different than elsewhere in Central Asia, where most everyone could speak at least a bit of Russian, and understood that Russian was the lingua franca that would most likely be spoken with people from another country or region (although, as I got a better ear for Russian, I was really surprised at how badly a lot of people in rural Uzbekistan spoke Russian, with pretty heavy accents and/or mangled pronunciation—sometimes it was even difficult to negotiate prices). So maybe this is a concrete result of Turkmenbashi's pro-Turkmen propaganda: a firmer and more resolutely-held belief in the value and importance of local customs and language.

Ashgabat, the city of love

Ashgabat literally translates as "city of love." What it is is a city in love with marble. Well, maybe that's unfair. The truth is that Ashgabat isn't that different than Astana in terms of being a modern capital that has been reconstructed and transformed with a spate of new buildings, just that the style of construction is very different. While Astana has consciously attempted to emulate a western style and has courted the famous architect Norman Foster, Ashgabat has taken a more idiosyncratic approach and followed the personal tastes of its nationalistic leaders.Turkmenbashi, Turkmenistan's long-serving President, was a man who was deeply in love with marble, fountains, and himself. So most of the buildings and monuments constructed before his death are marble, have fountains, and include monuments to himself. Ashgabat. In fairness, Turkmenbashi's successor is less enamored of marble, and the architecture incorporates more glass and has a more modern—though not necessarily attractive—look.

Who is this Turkmenbashi, you ask? Well, like most other CIS 'stans, Turkmenistan

has had a de facto dictator in power since independence (Kyrgyzstan is

the only country that has broken the cycle and has had power transferred

between multiple elected leaders in contested elections). Saparmurat Niyazov, who assumed the Presidency after the Soviet Union crumbled, went on to cultivate the most massive personality cult in all of Central

Asia, not only doing the rather standard things like constructing dozens

of massive statues glorifying himself (in response to public demand, of

course), but also going so far as to rename himself Turkmenbashi

(leader of the Turkmen) and writing a book called the Ruhnama

that was designed to instil national pride and cultural and spiritual

instruction.

Given this massive personality cult, you might be surprised that Turkmenbashi is no longer President (especially since

Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan have all had the same

leader since independence), but the reality is that the second President assumed office only out of necessity, as a result of Turkmenbashi's death, whereupon power was transferred to his second in

command, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow.

After

rolling back some of Niyazov's more outrageous excesses and decrees,

and dismantling or moving some of his more prominent statues (including

moving the gargantuan "Arch of Neutrality,"

which included a massive gilded statue of Niyazov that rotated to

ensure he was always facing the sun), Berdimuhamedow has started to

construct his own personality cult, which although not as excessive as

Niyazovs is still greater than you see anywhere else in Central Asia.

In the west, Berdimuhamedow is probably more famous for one of his exploits gone awry:

after jockeying the winner in a horse race that was no doubt as fair

and free as the elections he has won, he promptly fell off his horse and

face-planted in the dirt. Apparently his security apparatus attempted

to delete all evidence of this from the cameras of those in attendance,

but the footage still made its way out. One thing that I found telling

is that there was only a slight gasp from the crowd as he fell, and the

subsequent reaction was very muted, even though they were clearly

assembled to cheer for their beloved leader.

As I walked from the station into the main area of the city, I was surprised to find that there were little underground passageways at the main intersections, and that these passageways opened up into small malls about the size of the intersection, lined with convenience stores and shops. Of course, I was there in the middle of the night, so none of them were open, and a security guard quickly showed up to ask what I was doing and shoo me back up to street level. These little shopping areas certainly seemed like they would be more lively than the ones I saw in Busan, however, which is the complete opposite of what I would expect. In general, shops in Ashgabat were modern and clean, with lots of imported things. And because so many buildings in Ashgabat are brand new, it made the country feel quite prosperous: simply visiting Ashgabat without visiting any of the smaller towns and cities in the country would give you a very different impression of what the country is like, as was immediately apparent from my time in poor, ugly Konye Urgench.

As the sun rose I returned to the station, bought a ticket on the night train to Mary (less than $3 for a spot in a 4-berth kupe compartment), and checked my bag into the difficult-to-find storage facility (it's on the east end of the building to the east of the main station building).

Bus shelters and stops in Ashgabat have maps of the routes that stop there, and I decided to take a bus to the southern edge of the city, from where I hoped to be able to to take the cable car that lead up the Kopet Dag mountains that form the border with Iran (supposedly in the summer high-ranking government officials have to walk up a path here as part of a fitness-oriented exercise, with the President helicoptering to the summit to meet them). Unfortunately, I wasn't able to find the where the route started, but I did spend a couple of hours puttering around empty plains south of the city, observing wide expressways virtually devoid of traffic on my way back into town. The problem is that I was on the north-south road that eventually leads to the Iranian border while the cable car is considerably to the west, and the TV tower is even further west.

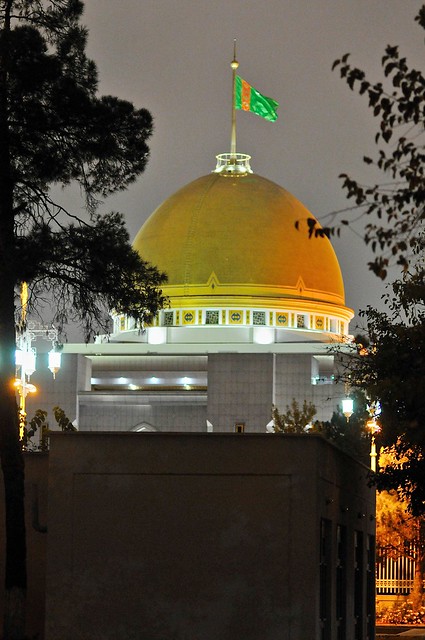

Along the road back into town is the long Independence Park, which contains a few monuments and is flanked by impressive buildings. Well, they're impressive if you think that Las Vegas is a classy place, as Ashgabat designers clearly do. White marble, gold domes, and lots of columns are the architectural staples.

Bus shelters and stops in Ashgabat have maps of the routes that stop there, and I decided to take a bus to the southern edge of the city, from where I hoped to be able to to take the cable car that lead up the Kopet Dag mountains that form the border with Iran (supposedly in the summer high-ranking government officials have to walk up a path here as part of a fitness-oriented exercise, with the President helicoptering to the summit to meet them). Unfortunately, I wasn't able to find the where the route started, but I did spend a couple of hours puttering around empty plains south of the city, observing wide expressways virtually devoid of traffic on my way back into town. The problem is that I was on the north-south road that eventually leads to the Iranian border while the cable car is considerably to the west, and the TV tower is even further west.

Along the road back into town is the long Independence Park, which contains a few monuments and is flanked by impressive buildings. Well, they're impressive if you think that Las Vegas is a classy place, as Ashgabat designers clearly do. White marble, gold domes, and lots of columns are the architectural staples.

|

| View through the scraggly Independence Park. The domed marble buildings are the National Cultural Center. |

|

| The mountains south of town form the border with Iran. That building rising into the mist in the foothills is the TV Tower. The access road to the cable car is located about halfway between where I was and the TV tower. |

|

| White marble apartment buildings surround the park. Since I was there even more parts of town have been torn down and replaced with rows or modern apartments. |

Continuing north through Independence Park you'll find another interesting building, this time a five-sided pyramid, with each of the corners a cascading waterfall. It's supposedly a shopping center, but was completely closed when I was there. My 85mm lens didn't really allow me to take any pictures, so I kept heading north until I found one of the only banks in Turkmenistan that allow foreigners to get a cash advance from their credit card. I turned up while the bank was closed for lunch, so I killed some time in the adjacent shopping center, which had a huge supermarket on the ground floor and an interesting cafeteria and amusement park and billiard center on the top floor. Supermarkets always interest me, and I wish I took more pictures of them (and quotidian street life): I think that traveling with a smartphone would have really made it more likely I would have taken these kinds of pictures, not least since it wouldn't look so strange and drawn attention.

After the lunch break I visited the bank and took out a few hundred dollars, knowing that I would have no chance to get my hands on any more money until I left Iran (it's impossible to use international credit or debit cards there). I met one other foreigner who was doing the same, this one a Kazakh-American working in the oil sector in Ashgabat.

From there I took a bus into town, and headed to one of the travel agencies to the east of the government buildings to ask if it would be possible to change the exit point on my visa (I still wanted to try and squeeze in a visit to Herat, in Afghanistan, which would only be possible if I changed my exit point, as changing my Iranian visa to a double-entry would not be possible). The agent said it probably wouldn't be possible but that I could visit the appropriate ministry to try, giving me their address. We had a brief chat about Turkmenistan and the difficulty in getting a visa for there, especially the near-impossibility of getting a visa in October, around Independence Day (October 27, though in practice almost nobody gets a visa valid for the latter half of October). His response—said with a straight face—was that so many world leaders come to Turkmenistan to celebrate Independence Day that the state had to take strict measures to ensure their security. Uhhh.... okay.

The travel agency was near the Azadi Mosque, which was clearly modeled on Istanbul's Blue Mosque, though obviously on a much smaller scale. This area of town remains largely Russian in appearance and layout, and is a refreshing change from the institutional and overbearing style of new Ashgabat: hopefully it will remain that way for the foreseeable future (older and poorer traditional-style districts will continue to be the focus, I'm sure).

After the mosque, I headed west through the modern park north of the government buildings, on my way to the Russian Market and the nearby immigration building.

After the lunch break I visited the bank and took out a few hundred dollars, knowing that I would have no chance to get my hands on any more money until I left Iran (it's impossible to use international credit or debit cards there). I met one other foreigner who was doing the same, this one a Kazakh-American working in the oil sector in Ashgabat.

From there I took a bus into town, and headed to one of the travel agencies to the east of the government buildings to ask if it would be possible to change the exit point on my visa (I still wanted to try and squeeze in a visit to Herat, in Afghanistan, which would only be possible if I changed my exit point, as changing my Iranian visa to a double-entry would not be possible). The agent said it probably wouldn't be possible but that I could visit the appropriate ministry to try, giving me their address. We had a brief chat about Turkmenistan and the difficulty in getting a visa for there, especially the near-impossibility of getting a visa in October, around Independence Day (October 27, though in practice almost nobody gets a visa valid for the latter half of October). His response—said with a straight face—was that so many world leaders come to Turkmenistan to celebrate Independence Day that the state had to take strict measures to ensure their security. Uhhh.... okay.

The travel agency was near the Azadi Mosque, which was clearly modeled on Istanbul's Blue Mosque, though obviously on a much smaller scale. This area of town remains largely Russian in appearance and layout, and is a refreshing change from the institutional and overbearing style of new Ashgabat: hopefully it will remain that way for the foreseeable future (older and poorer traditional-style districts will continue to be the focus, I'm sure).

After the mosque, I headed west through the modern park north of the government buildings, on my way to the Russian Market and the nearby immigration building.

|

| Ashgabat was leveled in 1948 by an earthquake measuring over 7 on the Richter scale. This is the memorial to the victims of that quake. Not having a wide-angle lens, I wasn't able to properly capture just how big this statue is, but that little golden boy is about the size of a man. Since he's a golden boy, he's obviously Turkmenbashi as a young boy, being saved by his mother, who died in the quake and left him orphaned (his dad died in WWII). |

The Russian Market was a bit different than most markets, though the central green market area most closely resembled Almaty's green market: a rectangular area covered by a high roof, surrounded by a balcony arcade. In this market, however, there were more shops on the upper floors and the entire affair felt much more airy and less closed. Again, photographic opportunities were limited because of my lens problem, and I really only had the working space to take pictures from the upper level overlooking the market. When I tried to do so, however, I was immediately spotted by someone, and was quickly approached to be told I couldn't take pictures (also similar to Almaty's green market).

After that I went to the immigration building, which was just across the street and a few doors down, and tried to see if I could get my exit point changed. After a few false starts I found the correct person to ask, and was unsurprisingly told that it wouldn't be possible. At least I tried.

The streets in Ashgabat are a bit weird, especially where new areas meet older areas, as wide roads suddenly squeeze into single-lane roads that head off in different directions, though some of the Russian-style boulevard parks are used as natural borders between the areas. I walked west along one of these narrow boulevard parks, towards the Mosque of Khezrety Omar in a traditional part of town. At the end of the park, a short distance from the mosque (which has now been bulldozed to make way for more apartment buildings) was the Monument to Turkmenbashi's Father (who, remember, died in WWII). Although this could easily have been retitled as a memorial to war dead in general, current Google Earth imagery seems to indicate this monument has been removed altogether (incidentally, it's fascinating to step back in time in Ashgabat via Google Earth's historical imagery).

After that I went to the immigration building, which was just across the street and a few doors down, and tried to see if I could get my exit point changed. After a few false starts I found the correct person to ask, and was unsurprisingly told that it wouldn't be possible. At least I tried.

The streets in Ashgabat are a bit weird, especially where new areas meet older areas, as wide roads suddenly squeeze into single-lane roads that head off in different directions, though some of the Russian-style boulevard parks are used as natural borders between the areas. I walked west along one of these narrow boulevard parks, towards the Mosque of Khezrety Omar in a traditional part of town. At the end of the park, a short distance from the mosque (which has now been bulldozed to make way for more apartment buildings) was the Monument to Turkmenbashi's Father (who, remember, died in WWII). Although this could easily have been retitled as a memorial to war dead in general, current Google Earth imagery seems to indicate this monument has been removed altogether (incidentally, it's fascinating to step back in time in Ashgabat via Google Earth's historical imagery).

The Mosque of Khezrety Omar was certainly busier than the Azadi Mosque—people apparently avoid the Azadi because a number of people died while it was being constructed in 1991—but rather pedestrian in appearance aside from its painted ceiling. Although the area is now a boulevard of modern apartments, even then there were signs of impending construction as I made my way to the Ten Years of Independence Park, which was just across from the World of Turkmenbashi Tales Amusement Park. In the Ten Years of Independence Park (not to be confused with the regular Independence Park, of course) there is another giant gold statue of Turkmenbashi—which makes sense since he was President ten years after independence—in front of a giant statue of the Akhal-Teke hoses that are emblematic of the country.

It was getting quite dark by this time, so I headed back to the train station and bought some snacks at a nearby supermarket before collecting my bag and having dinner at the station cafeteria.

The train to Mary was you standard-issue Russian train, with four comfortable bunks per compartment. I was a little surprised when I entered my compartment, as there were already four people in it, but it turned out that two of them were doubling up on the bottom bunk. I guess they must have run out of tickets, because the cheap train fares couldn't be a realist obstacle. Shortly after leaving the station an agent came around to rent out bedsheets for the trip. I declined, but from the her reaction I would gather that not many people decline them (certainly no one else in my compartment did).

Budget

November 13, from Ashgabat to Mary: 32 manat

- Tea and bread at chaikhana: 2 manat

- Train to Mary: 8 manat

- Bag storage: 1 manat

- Coke & coffees: 2 manat

- Ice cream & meat pie at shopping center: 2 manat

- 2kg mandarin oranges, wet & dry tissues, soups, two naan, chips: 12 manat

- City bus x 4: 0.8 manat

- Dinner (tea, bread, bread soup) at station: 5 manat