Actually, I don't love Hiroshima. That's not to say I dislike Hiroshima, because I don't. It's a pleasant Japanese city with surprisingly wide roads and a feeling of spaciousness heightened by the streetcars that (slowly) roam the streets.

Just as it forms the backdrop to Hiroshima Mon Amour, everything about our modern conception of Hiroshima is based on their status as the first place that an atomic weapon has ever been used against humans. That's what Hiroshima is, and what it means.

Perhaps understandably, there was considerable discrimination after the war against those who had survived the bombing. People were worried about radiation sickness, latent illnesses, and genetic deformities, which led people to attempt to conceal their backgrounds so that they could be hired or get married (two common acts that frequently involve background checks in Japan). Survivors wouldn't discuss it with their kids, and it remains a pretty taboo subject even though the fears that initially motivated the bias has been shown to be baseless.

But at the same time that Japanese society continues to victimize survivors, they use their status as the only country ever nuked as a way to play the victim and deflect criticism over their own conduct during WWII. Japan aggressively pushes their status as the only target of nuclear weapons while pushing for international pacifism and the abolition of nuclear weapons. Of course there's some hypocrisy to this, as Japan has a large military force (though because Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution—written under US occupation—prohibits Japan from having an army capable of aggression, these formidable forces are technically Self-Defense Forces), and uses nuclear power to generate a substantial portion of its energy needs. More importantly, however, is the way this Japan-as-victim-of-WWII narrative displaces any real conversation about what Japan did during the War or conceptualization of Japan as the committer of atrocities.

Ground zero for this narrative is, of course, Hiroshima, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in particular. With powerful exhibits and artifacts illustrating the breadth and depth of the devastation incurred on August 6, 1945, the museum is compelling but occasionally devolves into the maudlin. My impression is that it has improved significantly since I first went there in 1993, with additional (though limited) discussion of Japan's role in WWII, but it also remains true that it is a powerful tool to establish and affirm the prevailing narrative that Japan as been the only victim of the uniquely horrifying instruments of indiscriminate destruction that are nuclear devices.

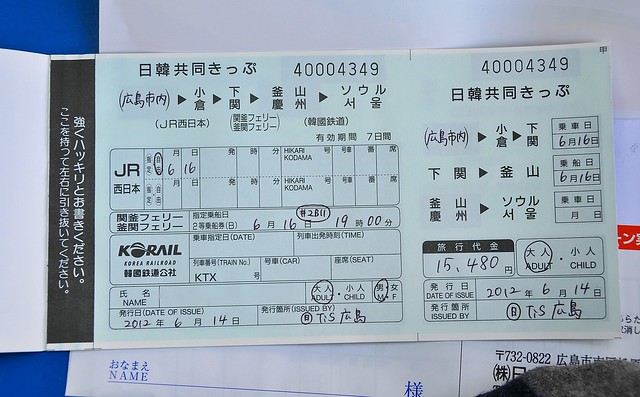

I had read that you could get a combination train and ferry ticket between Japan and Korea, and that these tickets were sold at a significant discount. It was fairly difficult to get information on these, even at the normally reliable seat61.com, but I discovered they were called nikkan kyodo kippu (日韓共同きっぷ).

These tickets allow for Shinkansen travel within Japan, ferry travel between the countries (you can take the fast and expensive Beetle ferry from Fukuoka, or the slow overnight ferry from Shimonoseki at the western end of Honshu), and then the fast KTX train from Busan to Seoul. Obviously, I am cheap so I took the overnight ferry, which also saved one night's accommodation.

I eventually found pricing information on a blog by Louise Rouse (her blog is now defunct, but you can still access a pricing pdf she made here). The only thing that remained was to actually buy the ticket. I discovered that you can not buy them at your average JR ticket counter, as they have no idea what these tickets are (even if you speak Japanese). In order to buy these tickets, you really do have to visit a travel agency. Thankfully, every train station of any size will have a travel agency somewhere inside the building or across the street. I bought mine in Hiroshima, and I was actually kind of surprised that the agent immediately knew what I was talking about and was happy to make me a ticket.

You are allowed to take up to seven days to complete your trip from the time you begin, and on my ticket I had to specify the shinkansen and ferry dates in advance (the date of the Busan-Seoul leg was left open, and had to be confirmed/exchanged for a proper ticket in Busan, which I did for a train that left 30 minutes later). You do not have to specify a shinkansen time at the point of purchase, and I believe you can take any non-Nozomi train and sit in an unreserved car.

If you are traveling from Korea, it may be easier to buy one of these tickets, as I saw it advertised at the KORAIL ticket office in Busan, and you can see Korean pricing here.

After buying my ticket I headed for one of the hills behind the train station. There was a Buddhist stupa at the top—a surprising sight in Japan, as you typically see these in SE Asian countries like Thailand and Burma. Apparently this is the Peace Pagoda, set up in 1966 in the name of world peace.

Shukkeien is close to a tram line, but in all honesty the trams in Hiroshima are so slow and stop so frequently (every block or so) that it is scarcely faster than walking; given that the main sights are in a pretty compact area, there's no real reason to take them.

Just as it forms the backdrop to Hiroshima Mon Amour, everything about our modern conception of Hiroshima is based on their status as the first place that an atomic weapon has ever been used against humans. That's what Hiroshima is, and what it means.

Hiroshima, nuclear weapons, self-victimization, and deflection

The Japanese have a somewhat strange relationship with Hiroshima (and Nagasaki). They are both the source of stigma, but also the source of a certain sense of moral authority.Perhaps understandably, there was considerable discrimination after the war against those who had survived the bombing. People were worried about radiation sickness, latent illnesses, and genetic deformities, which led people to attempt to conceal their backgrounds so that they could be hired or get married (two common acts that frequently involve background checks in Japan). Survivors wouldn't discuss it with their kids, and it remains a pretty taboo subject even though the fears that initially motivated the bias has been shown to be baseless.

But at the same time that Japanese society continues to victimize survivors, they use their status as the only country ever nuked as a way to play the victim and deflect criticism over their own conduct during WWII. Japan aggressively pushes their status as the only target of nuclear weapons while pushing for international pacifism and the abolition of nuclear weapons. Of course there's some hypocrisy to this, as Japan has a large military force (though because Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution—written under US occupation—prohibits Japan from having an army capable of aggression, these formidable forces are technically Self-Defense Forces), and uses nuclear power to generate a substantial portion of its energy needs. More importantly, however, is the way this Japan-as-victim-of-WWII narrative displaces any real conversation about what Japan did during the War or conceptualization of Japan as the committer of atrocities.

Ground zero for this narrative is, of course, Hiroshima, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in particular. With powerful exhibits and artifacts illustrating the breadth and depth of the devastation incurred on August 6, 1945, the museum is compelling but occasionally devolves into the maudlin. My impression is that it has improved significantly since I first went there in 1993, with additional (though limited) discussion of Japan's role in WWII, but it also remains true that it is a powerful tool to establish and affirm the prevailing narrative that Japan as been the only victim of the uniquely horrifying instruments of indiscriminate destruction that are nuclear devices.

|

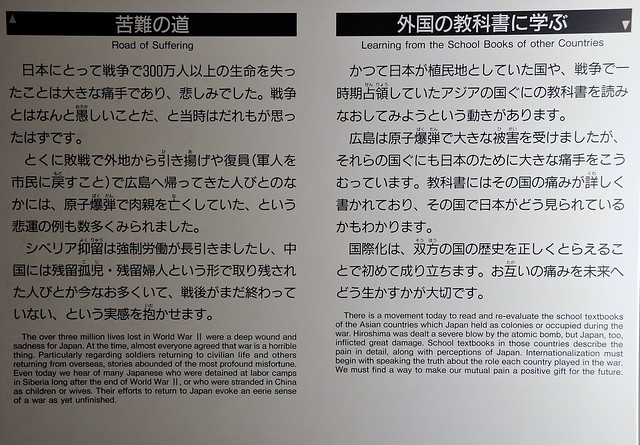

The text on the right actually counts as an improvement in how the Japanese address their role in WWII.

|

The Peace Park and A-bomb Dome

The iconic A-bomb dome is about 150m from the epicenter of the atomic blast, and the was one of the few buildings in the vicinity not to be totally leveled. The Peace Park is on the northern end of the island across from the A-bomb dome, and the northern tip of this island was the original targeting point of the bomb. |

| Children's Peace Monument, inspired by 12-year-old Sadako Sasaki, who died of cancer 10 years after the bombing. She wanted to fold 1,000 cranes as part of her wish for recovery, but was only able to make 664 before she died; schoolkids today fold cranes for this memorial in her honor. |

The mythical "Nikkan Kyodo Kippu" shinkansen-ferry-ATX ticket for travel between Japanese cities and Seoul

I wanted to take my entire trans-Asian trip without flying. Obviously, the first part of this would be taking the ferry from Japan to somewhere. Korea is the obvious choice, although there are also occasional ferries to Shanghai and a port near Beijing.I had read that you could get a combination train and ferry ticket between Japan and Korea, and that these tickets were sold at a significant discount. It was fairly difficult to get information on these, even at the normally reliable seat61.com, but I discovered they were called nikkan kyodo kippu (日韓共同きっぷ).

These tickets allow for Shinkansen travel within Japan, ferry travel between the countries (you can take the fast and expensive Beetle ferry from Fukuoka, or the slow overnight ferry from Shimonoseki at the western end of Honshu), and then the fast KTX train from Busan to Seoul. Obviously, I am cheap so I took the overnight ferry, which also saved one night's accommodation.

I eventually found pricing information on a blog by Louise Rouse (her blog is now defunct, but you can still access a pricing pdf she made here). The only thing that remained was to actually buy the ticket. I discovered that you can not buy them at your average JR ticket counter, as they have no idea what these tickets are (even if you speak Japanese). In order to buy these tickets, you really do have to visit a travel agency. Thankfully, every train station of any size will have a travel agency somewhere inside the building or across the street. I bought mine in Hiroshima, and I was actually kind of surprised that the agent immediately knew what I was talking about and was happy to make me a ticket.

You are allowed to take up to seven days to complete your trip from the time you begin, and on my ticket I had to specify the shinkansen and ferry dates in advance (the date of the Busan-Seoul leg was left open, and had to be confirmed/exchanged for a proper ticket in Busan, which I did for a train that left 30 minutes later). You do not have to specify a shinkansen time at the point of purchase, and I believe you can take any non-Nozomi train and sit in an unreserved car.

If you are traveling from Korea, it may be easier to buy one of these tickets, as I saw it advertised at the KORAIL ticket office in Busan, and you can see Korean pricing here.

|

My ticket. You can see the dates of

Shinkansen and Ferry travel are completed, but that the Busan-Seoul

segment is open and that I have not reserved a shinkansen seat.

|

After buying my ticket I headed for one of the hills behind the train station. There was a Buddhist stupa at the top—a surprising sight in Japan, as you typically see these in SE Asian countries like Thailand and Burma. Apparently this is the Peace Pagoda, set up in 1966 in the name of world peace.

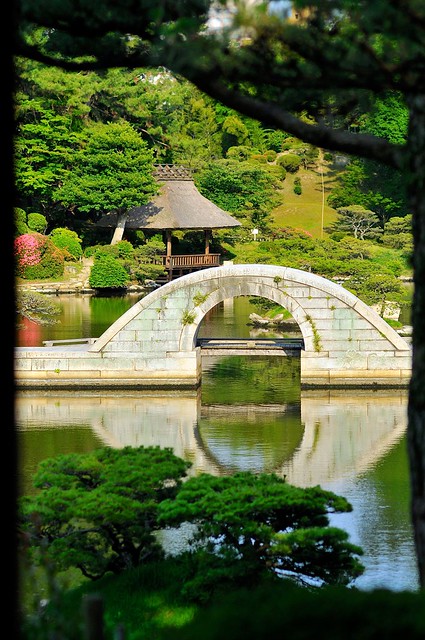

Shukkeien Garden

Apparently dating all the way back to 1620, this landscape garden isn't among the best Japan has to offer, but it's still worth seeing in Hiroshima. This is a circuit garden, where you're intended to follow a path around the central pond that reveals different views along the way. Unfortunately, there are now a lot of tall apartment buildings that didn't exist in 1620 (or when the garden was rebuilt following WWII), and they are quite visible from many points along the circuit.Shukkeien is close to a tram line, but in all honesty the trams in Hiroshima are so slow and stop so frequently (every block or so) that it is scarcely faster than walking; given that the main sights are in a pretty compact area, there's no real reason to take them.

|

| Irises in front of the teahouse. |

|

| Thatched pavilion seen from the start of the circuit. |

Hiroshima Castle

Like many sights in many places in Japan, Hiroshima Castle is a post-war reconstruction of the historical castle, which was destroyed by the A-bomb. They're typically pretty well done, to the extent you can't really tell how new it is. Or maybe you could, if only you had genuinely old castles to compare them to. |

| The castle and foundation stones. |

|

Almost as majestic...

|

A Turk living in Germany: race and identity in homogenous cultures

At the hostel in Hiroshima I met a guy who was traveling

alone and interested in talking. This, in istself, is a little unusual

in Japan: because of the relatively high cost of accommodation

(especially in places that attract English-speaking guests), hostels in

Japan tend to attract people traveling in groups, as opposed to solo

travelers.

Hiroshima doesn't attract the visitors that

Tokyo or Kyoto does, and property prices are undoubtedly cheaper, which

likely leads to more relaxed and less institutional hostels.

Anyway,

we asked each other where we were from. I said that I was from Canada,

and he answered that he was a Turk living in Germany. This seemed like

an unusual answer—I've lived for multiple years in both Japan and the

US, but I've always identified as Canadian—so I asked him how long he

had been in Germany. The answer: his entire life, as he was born there. I

knew that there was a long history of Turks in Germany—hundreds of

thousands of them were invited to Germany as "guest workers"

in the 1960s, with the intention they and their families would return

to Turkey after working in Germany—but his answers was still very

difficult for me to comprehend as a Canadian. I said as much, saying

that anyone born in Canada would call themselves Canadian, as would the

majority of people who have immigrated to Canada and obtained Canadian

citizenship. But as strange as his self-identification seemed to me, I

suspect he found it just as difficult to understand how even the newest

of Canadians, regardless of the origin, could identify as Canadian.

I

think a lot of people like to blame immigrants for failing to integrate

and assimilate to local customs. But it's difficult for people to do

this when native society doesn't actually accept or welcome newcomers,

and repeatedly reminds the newcomers that they are different, and will

not be accepted as natives. This Turkish-German talked about how

difficult it was as a child to make German friends (and I use the word

German to refer to white, ethnic Germans, because until recently it was

quite difficult for even native-born and raised children of non-German

parents to become German citizens), as with rare exceptions their

parents would not encourage their relationships and invite them to

events that they would invite other German children. The deep historical

ambivalence of Germans towards their Turkish "guests," with the

expectation they would return to Germany, and the only begrudging

realization that Turkish families who had lived in Germany for years,

and had children there, would be reluctant to leave and return to their

homelands.

A Canadian in Germany: what do see when they picture Canadians?

I

am half Japanese. When I was a kid, growing up in a town on the

Canadian prairie, I was often reminded that I was different. I had

teachers ask me where I was born, as well as more direct and explicit

racism from other kids. But when I moved to Calgary, and started going

to a high school that had a large contingent of Hong Kong Chinese

students, as well as Sikhs, Muslims of sub-continental extraction,

Lebanese, etc., I looked relatively 'normal' in comparison. Indeed, For

the most part, race became an inconsequential part of my identity, and

to the extent I was half white, I was less identifiable as a minority

than many other kids. And this image has stuck: I don't think of myself

as looking like a minority or looking any different than anyone else.

And in most Canadian cities, I don't think I look particularly ethnic to

most other Canadians; and if I do, it's not something that anyone

really spends much time thinking about.

I am most

reminded of my ethnicity when I travel. In most other countries, it's

readily apparent that I am not white, and this often causes some

confusion (or denial) when I say that I am Canadian. Sometimes this

means I can pass as a local. When in Europe I often passed for Italian

and Spanish, while in Malaysia I passed for Indonesian (and was arrested

as a suspected illegal worker when I ventured outside to a 7-Eleven

without my passport on day). I've passed for Kyrgyz, and Kazakh, and in

Iran almost everyone seemed to think I was Iranian. Sometimes it's nice

to pass, while other times you miss out on a certain amount of white

privilege and exoticism that goes part and parcel with being a Western

traveler in a foreign land. But for all it's pluses and minuses, it's

always interesting to see how other people in other cultures think of

what it means to be Canadian, and what it means to be a citizen of a

multicultural Western society.

Germany, 2002

I

spent a few weeks in Germany in the spring of 2002, and I stayed for a

couple of days with a German student, Konrad, that I met in Strasbourg

or Nancy. He was studying architecture in Dresden, although both he and

his flat-mates were all from West Germany.

At the time,

Canadians needed visas to visit Czech Republic, and I applied for my

visa in Dresden. I ended up staying in Dresden for a couple of days

while I applied for my visa, then leaving for a week or so to visit

nearby places like Erfurt, Weimar, Dessau, Quedlinburg, Leipzig and a

few other places while my visa was being processed. When I returned to

Dresden, one of Konrad's flat-mates told me that he was surprised I had

gone to visit those places. I asked what he meant, he said that there

were a lot of neo-Nazis in small towns in the East, and that if he

wouldn't want to travel to towns like that if he looked like me.

Although

I think his concerns were extremely disproportionate to the actual

threat of neo-Nazism and post-unification discrimination, he did remind

me of just how unrealistic my self-image as a normal and visually

indistinguishable Canadian was from how those (especially those from

racially homogenous cultures) view me.

I was reminded

again of this difference when I met another of Konrad's flat-mates, who

was a little confused when I said I was Canadian. He didn't ask the

annoying "But where are you really from?" question that some

people ask, but his response was even more unusual: "Are you an Eskimo,

then?" I have never met an 'Eskimo,' or Inuit. Inuit make up only 0.2% of the Canadian population,

and most of them are in Northern communities. I'm not sure if his

question demonstrates an ignorance of the multicultural nature of

Canada, or a inability to understand that those multicultural citizens

would actually identify as Canadian.

I don't mean this

as an indictment of Germany in particular (although it's clear that

their approach with regards to guest workers was myopic and that they've

failed to effectively integrate and welcome immigrants, despite multikulti), as I think that this is probably pretty reflective of most cultures that have long, established, mono-ethnic cultures.

Full Circle

In

this context, however, I think that this Turkish-German's

self-identification makes sense. Born in Germany, but not a German. Of

Turkish ancestry, but not really Turkish, either.

No comments:

Post a Comment