Carpet Factory

On this visit to the carpet factory there were a lot more weavers about, and I was able to wander around and view more of the buildings. You could see the facilities where they washed and dyed the yarn, where they washed the carpets, as well as a shop where they displayed completed carpets. All of these rooms and buildings were completely empty, however (even the shop/storeroom), and I get the sense that they really only gear things up and staff the shop when they have a tour group coming through. That's fine with me, as it was nice to be able to simply wander around.

|

| Two weavers working on a small carpet. |

|

| On larger carpets, more weavers work. |

|

| Watching them work, it's evident how huge an investment in time hand-knotting carpets is. The fact that they're even somewhat affordable is a testament to how underpaid the weavers/knotters are, and it's no surprise that child slavery is used in South Asia or that many carpets are made by women who are culturally unable to work outside of their home. |

|

| They say that weavers can tie about 10,000 knots per day. Assume a knot density of 200 knots per square inch on this rug (which would be considered very good, but far from the 600+ found in ultra-fine rugs) and that's only 50 square inches, or about 2 inches of vertical per day on this carpet being woven by 6 women. If this carpet is 20 feet long, it will take 6 women 120 days of weaving to complete it. This kind of puts the price in perspective. |

|

| Camels grazing by the side of the White Jade river. It looks like camels can eat anything. |

|

| Is that camel on the left super-pregnant, or what? I don't know, because other camels were still nursing their young. It appears they don't wean their calves until they're up to 2 years old, though. |

|

| Mother and child. |

|

| I think I like camels more than horses. They seem to have distinct and readily-apparent personalities in way that horses do not, which makes them easier to relate to or understand—even if their personality frequently manifests itself in surliness. |

Atlas Silk Workshop

From the carpet workshop, you turn right along the road as you exit and walk north for a while until you pass under another large road (this is the road that the buses to Jiya take). Keep walking north until you get to the petrol station and truck stop on the right, as the buses to Jiya will stop here if you flag them down. Probably any small buses that passes here is on its way to Jiya, but look for the Chinese "吉亚乡" to be sure. Tell the driver you want to go to the Atlas silk workshop (they tend to recognize "Atlas"), but keep your eyes peeled because my driver forgot about it while talking to passengers. Atlas is the Uyghur word for the

Ikat dyeing process, as is commonly seen in women's dress in Xinjiang.

When open, the silk factory is interesting, and you might be able to see all aspects of the Ikat-manufacturing process, from the raw silk cocoons to the boiling and spinning of the yarn, to the tying and dyeing process, to the weaving of the fabric. Of course, there's a shop in the center of the facility (the production buildings ring the central courtyard), but there's also no pressure of any sort and you're free to just wander around.

The workshop was quite interesting. If you're headed to Margilon, Uzbekistan, there's a silk workshop there, too, which you can also visit. The Margilon workshop is perhaps a bit more comprehensive and organized, and you'll be escorted by a guide as well as have the opportunity to see commercial weaving machines in operation.

|

| Raw silk cocoons stored outside. |

|

| The cocoons are heated and softened, then strands of silk are teased from them, gathered, and collected on a spinning wheel. |

|

| Spinning silk on a bicycle wheel. |

The silk is prepared for dyeing by running silk thread over a stand, looping the thread back and forth, and then gathering them into bundles. These bundles are then tied (or taped) together in geometric patterns, and the dyed: the taped areas resist the dyes. This is then repeated until you get the desired coloration, with the lightest dyes being applied first.

|

| The pre-dyed warp threads on the loom, while the weaver throws the weft shuttle back and forth. |

|

| The loom setup: a ball of dyed yarn runs to the stone weight, which provides tension to the loom. There the yarns are split up and arranged into matching geometric bundles which are run over the loom. |

|

| A lot of work goes into a $10 scarf. Either that or the $10 scarves are not hand made. |

|

| A male weaver! He invited me to throw the shuttle a few times. I would make a lousy weaver. |

There's a scene in

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia where the police, who are searching for a body in a back-water village in Turkey, happen upon an outrageously attractive girl who serves them tea at an otherwise unprepossessing teahouse. Everythng in the films stops at that moment, as all the characters are stunned into silence by her beauty, yet none of the comment on it.

Something similar happened at the workshop's showroom. There was this young Uyghur girl, maybe 17, dressed in a gorgeous light green and tan silk dress and scarf, with light green eyes and a pale complexion. She looked something like the famous green-eyed girl on the cover of National Geographic, but less wild and more European. Stunning. As with the Hui girl in Dunhuang, she was someone I would have loved to take a picture of, but there's no way I could do so without feeling somehow intrusive or pervy about it.

Tomb of the Four Imams (Asim Imam)

Sometimes I wonder if Lonely Planet writers really visit the places they write about. I mean, I already know from my time in Kharkhorin that Michael Kohn researched things by reading other people's blogs, but when reading what he had to say about Asim Imam I really had to question if he had even visited it. He simply writes that it has "an interesting cemetery" and is a good place to "slide down the sand dunes." I'm not sure what kind of image that paints in your mind, but it certainly didn't suggest to me what I actually saw. Sure, there are dunes, but they're hardly of the height you would slide down (unlike in Dunhuang, where there are actual toboggan and inner-tube slides), and to say that it is an interesting cemetery is a bit like saying an ossuary or a catacomb is an interesting cemetery. In reality, Asim Imam is unlike any "cemetery" you are likely to see in China or Central Asia, as the graves or tombs are flag-festooned poles in the desert. These structures strongly resemble Mongolian

ovoo and Tibetan

latse, and it's unlikely a coincidence that the tombs commemorate a Muslim general who

turned the region towards Islam and away from Buddhism with his conquests. As with the

ovoo and the

latse, these structures

seem rather shamanistic when compared to mainline Islam burials, and the fact that local women make wishes and puncture the bark of nearby trees to see if their wishes will be granted (if sap runs, they will) is another telling sign of this.

|

| Tombs in the desert, unlike any Muslim tomb you're likely to see again. |

|

| Uyghur on a pilgrimage. |

|

| The walk to the mosque is littered with tombs. |

|

| Dunes with the mosque dome in the background. |

|

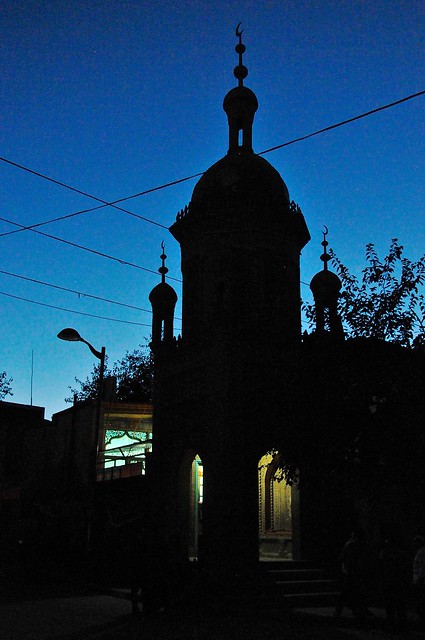

| The minaret towers over the grape vines that provide shade. |

|

| The tomb of Asim Imam. |

|

| Looking at the minaret through raisins curing on the vine. |

|

| Looks pretty similar to a Tibetan latse to me. |

|

| Giant slabs of coal next to the irrigation canal, on the road through Jiya. |

|

| Corn fields beyond the poplar-lined street. |

|

| I think of this road often, as it was about 20 kilometers of poplar-lined tarmac filled with the warm and friendly faces of traditional Uyghur. It's everything I had hoped I would be able to find in Central Asia, with the real surprise being that I found it in China. |

|

| Motorcycles and trikes for the Uyghur. In Han China proper cars would be more typical. |

|

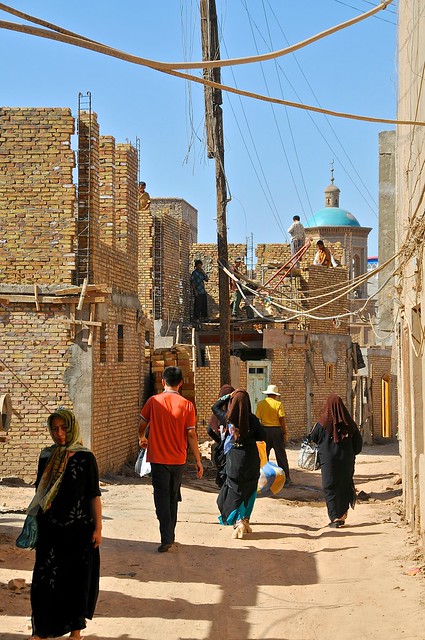

| Call to prayer near the carpet factory. |

|

| There's absolutely nothing unusual about this scene in Hotan. |

I wound up my time in Hotan by walking around and looking at some of the more modern shops around the city center. They're not nearly as interesting as the Uyghur sections and the traditional market, but probably a sign of what's to come.

I then went back to Marco's Dream Cafe—the owner was surprised to see me since she knew I was only staying for the day the last time I was there—where I repaid my debt to her travel binder by adding my own note about how to get to all the sights in and around Jiya. Hopefully future visitors to her cafe will buy more than I did (her Malaysian food is quite good and would be a nice reprieve for those wanting a change from Uyghur and Chinese food).