Five Graves to Cairo? How about eight rides to Konye Urgench.

The day I exited from Uzbekistan to Turkmenistan was one of the very few hard deadlines I had on my trip, as my 5-day Turkmen visa began on the the last day of my Uzbek visa. And because Turkmen transit visas specify the entry and exit border points that must be used, I knew I would have to be at the Khojeli/Konye Urgench border that day.

Now, Khojeli is the border between Nukus and Konye Urgench, and given the relative size of Khiva, Nukus, and Konye Urgench, you wouldn't think it would be that difficult to arrange transportation between them. You, however, would be wrong.

The first thing to do was get from Khiva to Urgench: Khiva is south of the main routes between Bukhara and Nukus, and so most transport not heading across the border to Dashogus instead goes through Urgench. The American guy who was also staying at the Lali Opa was headed into the Uzbek desert and then on to Kazakhstan, so we joined together in taking a taxi to Urgench instead of taking the slow trolley bus. Strangely, however, once we were dropped in Urgench there didn't seem to be any cars heading west, and after searching around the bazaar for a while the American—who spoke pretty decent Russian after a few months in Central Asia—discovered that we would have to go to Beruni to find a ride. In Beruni he helped me find a marshrutka to Nukus, and then we went our separate ways as he tried to hitchike on the main road.

After waiting only about a half hour for the marshrutka to fill, we were on our way to Nukus. Of course, it turned out that we only went to the outskirts of Nukus, and needed to transfer to share taxis to get all the way into town. So I piled into a car with some helpful Uzbek babushkas and we were off to the central market. Once there I had to negotiate a bewildering car lot, where cars seemed to be organized according to destination, but really weren't. After futilely asking drivers for a few minutes, a fellow passenger helped me out and found out where cars to Khojeli left from. After the usual wait (pretty short, as the market was busy), it was off to nearby Khojeli. At Khojeli we terminated at the share-taxi and marshrutka lot, where once again it was surprisingly difficult to find out who was going to the border. They had a weird system where, instead of people getting into cars destined for a specific place and waiting for them to fill, people who wanted to go somewhere would kind of just stand around, then magically a car/marshrutka in that destination would be decided and everybody would pile on. But in the meantime you just stand around, which leads to a feeling of tremendous uncertainty (both in terms of whether a vehicle would arrive, and whether you would be able to get a spot in it). After a while a marshrutka for the border showed up and we all piled aboard.

By this time it was well after noon, which isn't a good thing when you only have five days in a country (I can understand why cyclists often camp at the border so as to cross first thing in the morning).

At the border there were maybe 75 people lined up on either side of the road, in front of a barrier across the road. The customs station was about 50 meters beyond that. I already had visions of a repeat of the endless waiting I encountered at Dotsyk, especially since there was no indication on what side we should line up. A border guard was hanging around the barrier, and I got his attention by standing between the back of the lines, making a shrugging gesture, and gesturing to ask which line I should join. He pointed to the left, and shortly after joining that line he came and beckoned me to the customs house—this was actually another of the hoped effects of getting his attention: skipping the queue by playing the foreigner card (which isn't unreasonable since we pay way more than locals do for visas).

Getting out of Uzbekistan wasn't as difficult as getting in, as they didn't really check my hotel registration slips (though they took them), didn't check how much money I was taking out (if you leave with more money than you declared on entry, they may seize it—my dollar withdrawals in Samarkand basically only covered how much I spent in country), didn't check my pictures, and didn't check my computer.

There is a fairly short no-man's-land between the border outposts: less than 500 meters, according to Google Earth. I set out to walk it, but the border guards stopped me and told me that you needed to take the shuttle bus between the outposts. No foot traffic was allowed, so I reluctantly got on the bus with the locals, whereupon I had a problem paying: I had already used all of my Uzbek sum (except for a small 500 som note for souvenir purposes), I had no Turkmen Manats, and the only small demoninations I had in dollars were the $12 I knew I would need as an entrance tax for Turkmen immigration. The fee for this short little shuttle was something like $1, on the other hand, a substantial portion of which no doubt went to the border guards who forced everyone to take the van.

Thankfully the driver agreed to accept my Canadian $5—the only other small bill I had—but this caused some confusion as they discussed what the conversion rate should be. I think they must have confused the Canadian exchange rate with the Euro (or confused the colourful Canadian bill with a Euro note) because I ended up getting a weird rate, such that the value of change I got back (in a mix of useless som and manats) was actually greater than the value of the dollars I gave them—even if considered as US dollars, and not Canadian. Their confusion later caused some confusion on my part as to what the proper exchange manat exchange rate was, as based on the change I received it should have been about 4 to the US dollar, but in reality it was 2.85 to the US dollar (the exchange rate was fixed at 2.85:1 for a long time, though it changed to 3.5:1 in January 2015, likely to reflect the devaluation of the ruble).

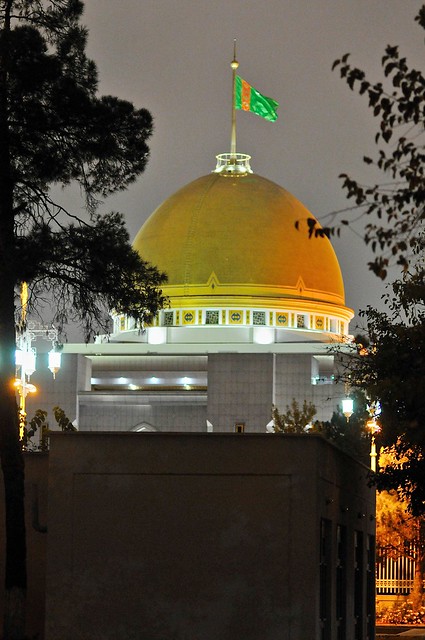

As we rumbled across no-man's land, looking out at the barren land, I had the strangest impression that it was winter—even though it was close to 20°C. I cam by this feeling honestly, however, as the marginal soil was white with salt stains, and bits of white fluff (cotton? pollen?) were floating in the air–in combination with the brown and leafless trees it all gave the impression of light snow. Very bizarre, but very convincing. This salty soil seemed characteristic of much of Turkmenistan; it's a good thing they have oil and gas, otherwise they would be in trouble.

Turkmen customs and immigration was different than I was expecting. Their systems were fully computerized and all entries were logged, which was actually a bit disappointing to me since it meant it probably wouldn't be possible to bribe my way out of a different border, and to cross to Herat. You have to pay a weird $12 entrance fee at the border to get into the country, which is a bit weird since you've already paid for a visa. I think they usually have change, but I figured they might not since they probably don't get many foreign visitors through this border point (or any), and I had $12 exactly. Paying the entrance fee and getting stamped into the country was sandwiched by getting my bag x-rayed and then inspected. One of the military guys assigned to the border post was a young guy who was eager to meet a foreigner and talk with me a little bit, and he was really friendly. I'm guessing that conscription is alive and well in Turkmenistan and that he had other things he would rather be doing. His colleague took his job more seriously, and was preparing to do a deep dive into my bag when the younger one waved him off and asked him why he was going to go to all the bother. The older one kind of rolled his eyes, but stopped searching.

After being stamped through and leaving the border point, we got onto one of the waiting shuttles to drive into town.

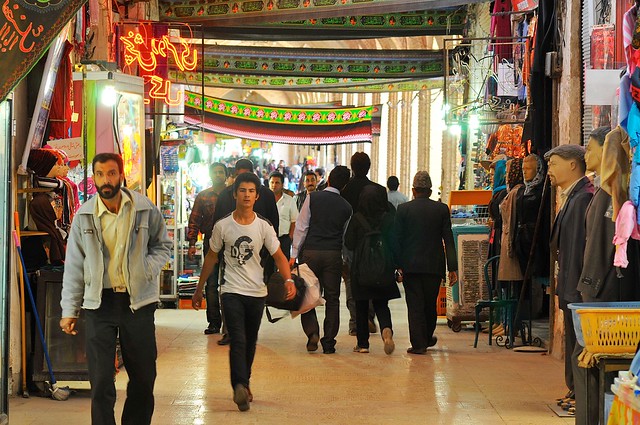

Hotels in Turkmenistan aren't particularly cheap for what they offer (partially because they are the only one of the CIS 'stans to continue to have foreigner pricing at official hotels, though it's usually phrased as a discount for Turkmen citizens), so when one of the other passengers in the marshrutka, upon hearing me name a hotel as a destination, insisted that I save my money and stay at his house (he had all been together since Uzbek customs, so he knew I had no manat), I accepted his kind offer. He lived on the northeast outskirts of town, a bit of a walk from the main road, but it was interesting to see a local neighbourhood. It, like pretty much all of Dashogus, was a relatively poor looking town, with older traditional Soviet-Central Asian architecture that wouldn't have looked out of place in rural Kyrgyzstan or Tajikistan. But at least he was at home with his family, unlike so many working-age men elsewhere in Central Asia.

At his home I met his wife and children, and after a simple dinner he popped in one of his favourite DVDs—a Shakira concert (globalization indeed!)—and we watched her hips not lie. Cheap pirated DVDs are ubiquitous throughout Central Asia, with fare running from Hollywood blockbusters to traditional music from around the region. Water for washing was from the usual jug and basin, much as in rural Sary Mogol, and the toilet was an outhouse on the other side of a small field behind his house. Although I always carry my own paper (wet wipes are great), as everyone does, there was a pile of rough, cheap paper that turned out to be pages from a mathematics book nailed to the wall. This kind of impoverishment would stand out in stark contrast to the excesses of Ashgabat, and when my host commented that Konye Urgench is an Uzbek town where almost everyone is ethnically Uzbek, I wondered if this was another layer in marginalization (like Uzbeks in Kyrgyzstan or Pamiris in Tajikistan); the only minority ethnicities who seem to have it okay are Tajiks in Uzbekistan (Bukhara and Samarkand being ethnically Tajik), though the Uzbeks retaliate by making relations with Tajikistan as difficult as possible.

The next morning, as I prepared to take my leave, I asked my host to point me in the direction of the nearest bank to change money. To my surprise, he insisted on accompanying me, even though I said it wasn't necessary. He said he would go with me and help me change money.

On the way into town we passed a bank, but we didn't stop there to change money (which made me a bit suspicious) but headed to the market. In the market he found a guy to change money, but the money-changer really wanted the transaction to be surreptitious, as though changing money (on what I assumed was the black market) was really serious. This seemed weird, as black market transactions in Uzbekistan and Burma are all done in the open, but he insisted on keeping everything out of sight. I'm still not sure what the big deal is, as by all accounts there is no black market in Turkmenistan and currency is freely exchangeable in both directions (i.e., they will change your manat to dollars when you leave at the same rate), and this market changer gave me the exact same 2.85:1 official exchange rate. Bizarre.

Anyway, after this, I thanked my host again, and expected us to part here. Probably I should have given him some money even though he had insisted I save my money by staying with him. But he said that he would accompany me and help me find a taxi to Ashgabat, where he could get me a ride for $30. Uh oh. According to Lonely Planet, a taxi should only cost 30 manat, which meant that he was clearly going to try and take a cut of this $30 for the $11 ride. This kind of put his "hospitality" in a whole new light. I told him that I would be OK finding one on my own and wanted to visit the monuments first, but he said he would accompany me.

Things got worse when we arrived at the archaeological zone, as although he accompanied me as I bought my admission and photography tickets, he really only wanted me to look at the first building and then peek at the minaret across the road before coming with him to get a taxi. He really didn't want me to take pictures, saying as it would cause problems for him. Now, maybe this would be a legitimate concern in this paranoid country, but since I had just bought a photography permit it didn't make much sense—my host tried to say that you could take one or two photos, but not many, and was eager for us to leave. I returned to the ticket booth, and asked the attendant there (who spoke very good English), and he said that I could take as many photographs of whatever I wanted. I obviously wasn't going to leave after only spending five minutes there, and my host decided he really didn't want to wait around for me, so although I thanked him for his hospitality I think it's safe to say we were both frustrated and disappointed with each other when we parted: he didn't get the payout he was hoping for, and I felt as though he was taking advantage of me under the guise of hospitality.

Anyway, I left my bag with the helpful and knowledgeable ticket attendant (I left it outside his little shack, but he kindly moved it inside with him—something that made me a bit nervous when I returned and didn't see it sitting where I left it) and headed across the road to explore the other monuments.

The Southern Monuments

Konye Urgench was the heart of the Khorezm empire which ruled the Amu-Darya delta area from the 10th century to the Mogol invasion in the early 13th century. The city was later abandoned when the Amu Darya, which formerly ran through the city, changed course and took up its current position through Nukus. The abaondonment of the city helped preserve the monuments, which are

now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The first building you come across on the road south of town is the Turabeg Khanum building, and it's one of the most interesting and impressive in Turkmenistan—though it would be a lot more impressive if it weren't right next to the highway with a big parking lot in front of it. The design of the building includes multiple references to the calendar, with the dome tiles having 365 sections representing the days, the lower level under the dome being a 12-sided dodecahedron to represent the months, four windows to represent the weeks in a month, and a tier of 24 arches between the ground level dodecahedron and the dome to represent the hours in the day. This building is usually described as a mausoleum, though apparently there are many who are less certain, given the lack of grave markers and other discrepancies.

If you remember from Samarkand that Bibi Khanum was Tamerlane's wife, you wont be surprised to hear that Turabeg Khanum was aslo a female: this time she was the wife of Gutlug Timur (who restored the Gutlug Timur minaret) and he daughter of Uzbek Khan (who was the khan when the Golden Horde converted to Islam).

|

| Bradt beats LP hands down for accurate, helpful information (but the most recent edition is from 2006 and is currently out of print). |

|

| In Uzbekistan this would be the basis for a restoration, not the result of one. Here, the exterior wall follows the 12-sided interior dodecahedron. |

|

| There are four of these big windows just below the dome. There are 24 of these arches, representing the hours in a day, and below them are the 12 arches in a dodecahedron. A better picture of the entire dome and the two tiers of arches can be seen here. |

|

| The tiles apparently divide the dome into 365 different sections. |

|

| View from Turabeg Khanum. |